For thousands of years, people have wondered about the mystery of consciousness. How can anything made of physical stuff – a brain, for instance – be identical to, or give rise to, a subjective experience? Despite a revival in the scientific study of consciousness over recent decades, the only real consensus is that there is still no consensus.

Into the fray steps Mark Solms with his intriguing book, The Hidden Spring – the culmination of a lifelong quest to understand the nature of consciousness. He brings a distinctive background to this task. His early training in neuropsychology, at South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand, provided him with direct insight into how brain damage can change a person’s experience of the world, and of themselves. Unusually, he then came to London to train in psychoanalysis – a field that had become increasingly marginalised from mainstream mind and brain sciences. But he has been a major voice calling for its reintegration, a pioneer of what is now called “neuropsychoanalysis”.

Solms’ debt to Freud is explicit through his book. He sees himself as continuing Freud’s incomplete project to provide a biological account of mental life. He decries the traditional emphasis of consciousness research on processes such as visual perception, arguing instead that the basis of conscious experience is to be found in how the brain perceives – and regulates – the physiological condition of the body. This perspective, which I have argued for too (although without the Freudian gloss), places feelings and emotions at the core of consciousness science, and Solms is at his best when exploring its implications.

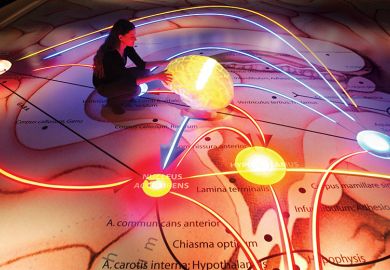

Less easy to swallow is his claim about where consciousness happens. Most neuroscientists believe that the cortex – the densely folded outer layer of brain that houses many billions of neurons – plays a necessary role. Solms demurs, arguing that the source of consciousness – the “hidden spring” of the book’s title – lies in the deeply recessed core of the brainstem. He provides us with evocative descriptions of “hydraencephalic” children – those born without much or any cortex but who still show emotional responses – as evidence that consciousness cannot depend on the cortex. If he is correct, the implications are substantial. But while Solms is right to caution against assuming that such children are not conscious, it remains a leap to assume the opposite, and his conclusions run counter to a large body of work showing that recovery from coma and the vegetative state is best tracked by what happens in cortical networks.

The Hidden Spring is not easy going. There is a wealth of neurobiological detail, not all of which seems necessary, and the lengthy exposition of the mathematically tortuous “free energy principle” is distractingly murky. Solms’ orientation to the surrounding literature can be uneven, leaving much to quibble with. Yet even if, like me, you remain unconvinced by his vision for neuropsychoanalysis, his analysis of David Chalmers’ famous “hard problem of consciousness” or his claim to have provided a blueprint for building a conscious machine, there is plenty to provoke and fascinate along the way. And the book’s primary message – that the source of consciousness is deeply bound up with our nature as flesh-and-blood living creatures – stands up by itself. Solms is one of a small number of scientists making this important argument, and for this alone his book is a welcome contribution.

Anil Seth is professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience at the University of Sussex and the author of Being You: A New Science of Consciousness (forthcoming).

The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness

By Mark Solms

Profile, 432pp, £20.00

ISBN 9781788162838

Published 28 January 2021

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Strong feelings for hard problem

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?