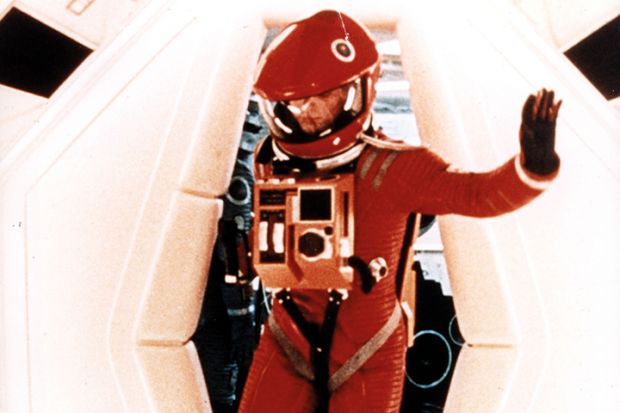

Stanley Kubrick has become the object of much recent academic attention, building on the unprecedented insights that we now can gain from access to his archive at the University of the Arts London. Given that this year marks the 50th anniversary of his magisterial 2001: A Space Odyssey , a flurry of books has been published. These include Piers Bizony’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, James Fenwick’s Understanding Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: Representation and Interpretation, Christopher Frayling’s The 2001 File: Harry Lange and the Design of the Landmark Science Fiction Film and Joe Frinzi’s Kubrick’s Monolith: The Art and Mystery of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

To all these we can add Michael Benson’s impressively researched and detailed account of the making of the film, based on the director’s own archives, those of his co-screenwriter Arthur C. Clarke and more besides. Benson has spoken to myriad participants, including Clarke, Kubrick’s widow Christiane, special effects supervisor Doug Trumbull and lead ape Dan Richter, and acquired interview notes from others. With almost 450 pages of main text, it represents a monolith in its own right. But, despite the voluminous research, it is a readable book aimed well beyond the academic market. As befits a science journalist, Benson does a masterful job of explaining the technical detail with which Kubrick brought space to life.

Benson’s book clears up the debate regarding whether HAL’s name was intended as a play on IBM. It was MIT artificial intelligence expert Marvin Minsky who suggested the words behind the acronym – heuristic and algorithmic (a seeming contradiction in terms) – and possibly the acronym itself. (But who besides Kubrick would design an advanced supercomputer and then agree to give it such a dull name as “Hal”?) What was Minsky’s reward? To have one of the hibernating astronauts whom HAL murders named after him! And the giant centrifuge that we see in the film did almost kill Minsky.

Other juicy titbits emerge. On set, HAL was often voiced by Kubrick, sometimes by a cockney. Kubrick, who had been a heavy smoker since the age of 12, was under pressure from his wife to quit. He took to bumming cigarettes off the crew to such an extent that they carried empty packets in their pockets to prove that they had run out. He soon caught on. Richter was taking legally prescribed heroin. William Sylvester (Dr Heywood Floyd) was also on drugs and fluffed his lines one too many times for Kubrick’s liking. Psychological manipulation was required to bring him around. Gary Lockwood (Dr Frank Poole) suggested the lip-reading sequence. The chess scene was not scripted and appears to have been pure improvisation. Keir Dullea (Dr Frank Bowman) came up with the idea to knock over the wine glass.

If there is a disappointing element to the book, it is that Benson does not provide a fresh reading of the film. Admittedly, this is beyond the scope of his account, but it would have been nice for him to have stuck his head above the parapet on the interpretative front in light of his impressive knowledge. Overall, though, this will probably be the definitive account of the making of 2001 for some time to come.

Nathan Abrams is professor of film studies at Bangor University. He is the author of Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual (2018).

Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece

By Michael Benson

Simon and Schuster, 512pp, £21.50

ISBN 9781501163937

Published 19 April 2018

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?