This sweeping history of the Peloponnesian War (431-404BC) begins with its origins in previous wars and carries on after its conventional end (the battle of Aegospotami, which culminated in the destruction of Athens’ fleet and its capitulation to Sparta). By extending her narrative to the battle of Leuctra in 371BC, when Sparta permanently lost its military dominance over the rest of Greece, Jennifer Roberts makes her conclusion especially clear: “there were no winners, only losers”.

The Peloponnesian War is a riveting subject, for at least two reasons. First, the main ancient source is Thucydides’ History – a masterpiece of lucidity and disenchantment, written during the war itself. In a year-by-year account, Thucydides sets out the development of the war between Athens and Sparta, and how it involved the rest of Greece. His general explanations highlight Sparta’s growing insecurities in the face of Athens’ ascendance, and the opposition between an authoritarian state and a mercantile democracy, but the value of his account is most apparent in his detailed analysis of events. This is, for example, how he describes the effects of a plague that broke out in Athens during the war and wiped out about one-third of the population: “People no longer strove to be honourable, because they doubted they would live long enough to earn a reputation for honour.”

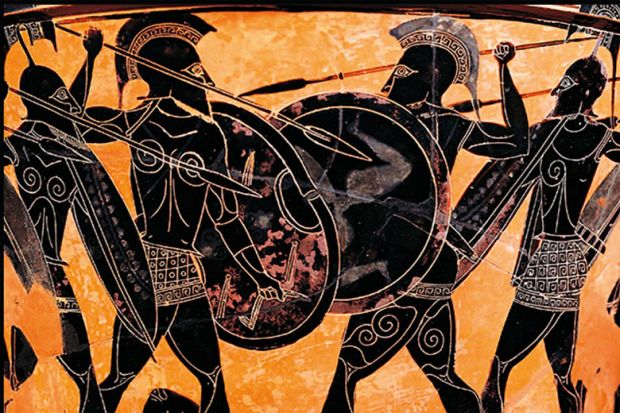

The second reason that the Peloponnesian War rewards attention is that it happened in a place, and at a time, that are interesting in many respects. This is when Athenian drama flourished, Phidias built the Parthenon, and Socrates troubled people with his insistent questions about truth, love, justice and the good life.

Roberts knows Thucydides intimately and follows his History closely. Her book is structured in lively short chapters, which include general discussion of classical Greek culture. Succinct footnotes point readers to ancient sources. In addition to Thucydides, she relies on several other ancient authors (Plutarch features prominently). She pays less attention to inscriptions and the archaeological record. Partly because of this, her account focuses (like Thucydides’) on a narrow cast of prominent men. Recent work on the ancient economy, slaves, women and ancient non-Greek views of the Greeks make little impact.

One respect in which Roberts differs from Thucydides – and from other accounts of the Peloponnesian War based on his History – is in her emphasis on chance and blunder. Thucydides described his work as “a possession for all times”. The main lesson Roberts seems to draw from it is that “things happen”. Ideological explanations (according to which, say, Sparta is like the USSR and Athens like the US; or, in more recent accounts, the US is like Sparta alarmed by the up-and-coming China/Athens) affect her narrative, but remain light-touch. Her position is, of course, ideological in its own right. War does not just happen, like an epidemic – no matter what Roberts’ title might suggest. It involves human volition. The ancient Greeks engaged in armed conflict almost every year (hence the difficulty in establishing the dates of the Peloponnesian War). Contemporary America is also regularly at war. Other cultures, however, place a higher premium on peace. Dare I say it, in the light of recent events: the European Union, anyone?

Barbara Graziosi is professor of Classics and head of department at Durham University, and author, most recently, of Homer (2016).

The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece

By Jennifer T. Roberts

Oxford University Press, 448pp, £20.00

ISBN 9780199996643

Published 16 March 2017