In this “part microhistory, part memoir”, Harvard University academic Jie Li recounts vividly and often poignantly the careers, ordeals and stories of several generations of her family, from Shanghai in the pre-Mao era, through the Communist agonies and into the reformist period.

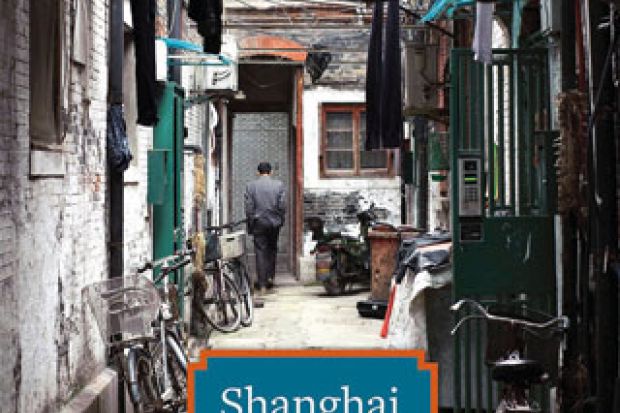

She zeroes in on two buildings in Alliance Lane in the Yangshupu District, one of Shanghai’s fast-disappearing traditional alleys, where rich foreigners and Chinese once lived, and, from 1937 to 1945, Japanese occupiers. After 1949, the labyrinthine streets would become warrens stuffed with people from all over China, living together higgledy-piggledy.

Li left China when she was 11, and returned to the alleys six years later in the 1980s to visit her family. In later years, she came back to record what they said – reliable or not – and, with the help of video and delicate drawings by her parents, to depict what family members’ lives had been like in the course of the tumultuous 20th century. She makes plain here that what she was after was not an accurate accounting of the facts of the past but rather the layers, the palimpsest, of what people remembered, half-remembered, had hidden or disguised, or chose to reveal. Li skilfully organises these overlays into an account of what the houses and their interiors looked like in their various incarnations, what was in them, and finally into recollections of long-ago talk, chats and gossip.

By the time we reach the Mao era, the stories become increasingly grim, even though some family members were initially keen on the revolution, or at least gave that impression. Through their accounts of being labelled and relabelled exploiters and “capitalist-roaders”, sent to the countryside, subjected to public humiliations and beatings or imprisonment in makeshift jails known as “cowsheds”, we can sense what Mao and his followers destroyed and reshaped.

There are endless ironies. As Li recounts, when the Red Guards ransacked homes and confiscated “bourgeois” books, covert circulation of the works of Western authors such as Dumas, Tolstoy and the Brontës developed and “all became enchanting, mysterious, and illicit names. Under their spell, many alleyway children did more reading during the Cultural Revolution than at any other time in their lives.” When Li asks an elderly relative why she had never married, she replies, “My ideas about marriage…came from my reading of Western novels and lyric poetry during the Cultural Revolution – Pushkin, and Tolstoy…hand-copied books secretly circulated among my alleyway neighbors… I conceived of love as a spiritual matter rather than a material one.”

Some accounts are tragi-comic: one politically sound relative interrogated fellow workers with “bad” class backgrounds, who duly wrote increasingly dark versions of the obligatory confessions about thefts from the workplace. The sums embezzled grew ever bigger and the interrogator dreamed he would become a Party member. But eventually the thefts claimed amounted to more than the value of the entire enterprise, and so “the culprits were all innocent again”.

After the demolition of their Alliance Lane homes, Li’s family members moved to sterile high-rises, bereft of most past possessions but not the layers of their memories. Observes one relative: “The palm does not see the back of the hand. You never know what will happen tomorrow, so better not act too smugly today.”

Shanghai Homes: Palimpsests of Private Life

By Jie Li

Columbia University Press, 280pp, £62.00 and £20.50

ISBN 9780231167161, 1167178 and 1538176 (e-book)

Published 18 November 2014