In their lively chapter on the treatment of religious women by modern, mainly male, historiographers, Jan Gerchow and Susan Marti begin by citing a common and, to their mind, persistent, view of the artistic and intellectual output of medieval women as worthy but, on the whole, without much merit. The rest of this wide-ranging collection, which outlines developments in the history of female religious communities in the period 500-1500, demolishes such a notion, offering the reader fascinating glimpses into the lives of religious women who emerge as thinkers, authors, theologians, artists - even as powerful politicians and administrators. Their approach to religion and art was, as Caroline Walker Bynum notes, marked by "the extravagance of language and behaviour often attributed to it, (and) by inwardness, theological subtlety, and a paradoxical union of community and service with contemplation and renunciation".

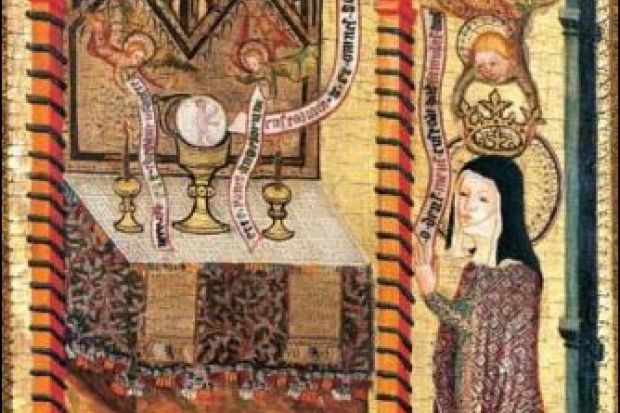

While much scholarly work has looked at the lives of religious women, this collection addresses a wider audience. It offers an overview without obscuring the complex details. Based on the catalogue accompanying an exhibition entitled Krone und Schleier (Crown and Veil) that took place in 2005 in Essen and Bonn, the collection manages to brook this generic shift by including 41 illustrations of miniatures, textiles, sculptures, paintings and liturgical objects produced by, and for, religious women. Women are shown to have been active as artists and commissioners of art, frequently making artistic objects the focus of their own, intensely personal, devotion to Christ. As Jeffrey F. Hamburger notes: "Enclosed women did not merely participate in the broader artistic currents of the Middle Ages; they consistently changed their course."

The close connection between religious women and visual culture is shown to be central to how women authorised their religious experiences, and to contemporary views of women as particularly susceptible to temptation. This perception certainly played a part in a call, issued in 1298, for stricter enclosure of religious women. One effect of this demand was a greater financial and spiritual dependence by female communities on their founders and on male clergy. This resulted in sometimes close and supportive - but often tense - relationships between male and female members of religious orders. Because only men could perform the duties central to pastoral care (preaching, hearing confession, celebrating Mass), they were central to the women's lives. At the same time, power struggles were common, and the collection illustrates some of the spirited reactions by religious women who sought to defend their ways of life. Communities were remarkably diverse: not only do they change as they are swept up in wider political and religious currents, they are also influenced by familial and regional contexts.

The 12 clearly written chapters introduce a range of female communities and the architecture of their buildings; the texts they produced and used; the importance of liturgy and ritual to their lives; their relationships with founders and patrons; the economic problems they faced; and their relationships with the world. While there is some overlap between chapters, rarely is there repetition. Rather, the pieces speak to each other and, as they address different but related aspects of medieval female piety, this serves to make the collection remarkably coherent. I recommend it to all readers interested in the history of art, women and religion.

Crown and Veil: Female Monasticism from the Fifth to the Fifteenth Centuries

Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Susan Marti

Translated by Dietlinde Hamburger

Columbia University Press 344pp, £23.50

ISBN 9780231139809

Published 6 June 2008