Posterity, it turns out, has not been especially kind to the artist Benjamin Robert Haydon, who is, these days, largely relegated to a footnote in the annals of early 19th-century painting. But he was once, as Stanley Plumly gamely protests in this book, “England’s leading history painter”, the friend of John Keats, William Wordsworth and Charles Lamb among others, and patronised by Sir Robert Peel, the prime minister of the day. It is certainly true that Haydon had a gift for falling into the orbit of an illustrious and brilliant crowd, and the summit of all this was, perhaps, the evening of 28 December 1817, when Haydon assembled a starry array of friends for a dignified evening of wine and poetry. In the event, the affair was a great deal less dignified and probably more drunken than anticipated, with several of the parties involved recording the various infractions of the evening. For Haydon, though, the “immortal dinner”, as he grandly christened it, was the apex of his achievement, a manifestation of the spirit of the age in which his own part was absolutely central. How far the latter is true and not simply the conjecture of Haydon’s wildly immodest imagination is difficult to discern, and Plumly’s reverential reading of the whole affair is not especially instructive.

Keats, Wordsworth and Lamb, among others, had gathered at Haydon’s Lisson Grove studio in London, specifically to toast the (near) completion of his great project: a large-canvas history painting titled Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem. Amid its crowded scene, the three poets’ faces can be discerned alongside equally anachronistic figurations of Voltaire and Newton. There was always something a little queer about Haydon’s project in the first place – not least Keats’ real-life atheistic unease – but Plumly’s awed narration tends to overlook such problems. Indeed, apart from its starry cast and the occasion of the “immortal dinner”, the painting itself is not especially brilliant. Plumly is helpful in explaining the logistics of producing works of this scale – how one manoeuvred around a tilted canvas in a cramped studio, etc – but his extended reading of the painting itself fails to lift it. Indeed, his own prose tends to sycophancy and romantic platitude rather than insight. He is right, though, to note Haydon’s exceptionally important role in the authentication of the Elgin Marbles, and the precise skill of his portraiture. Haydon’s Wordsworth upon Helvellyn is probably the most familiar depiction of the stately poet, and better still, his almost throwaway preparatory sketch of Keats, an 1816 sepia-inked profile hastily delineated on white paper, provides the most evocative and intimate image we have of the younger poet.

Yet the difficulty with Plumly’s book is that although its premise is a good one – the spontaneous gathering of Wordsworth, Lamb and Keats is a remarkable occasion – the event itself is perfectly well recorded by the parties involved and Plumly’s own theatrical, irritatingly present-tensed rendering lends it no further sophistication or understanding. Indeed, Plumly, perhaps discourteously, only fleetingly mentions Penelope Hughes Hallett’s earlier study, the excellent The Immortal Dinner (2000), in order to quibble with it. In fact, Hughes Hallett’s thorough and thoughtful book sheds more light on several of the other guests, particularly the genial young doctor Joseph Ritchie, and his fatal African expedition to locate the origin of the River Niger.

Plumly’s efforts are mostly directed at a Haydon he believes to have been neglected in the general Romantic narrative. And although that may be so, his argument is hampered by the book’s limited framework. He can provide only a thin account of the painter’s tragic final years and death by suicide – material that might have served to leaven the otherwise dominant notion of Haydon as a sycophantic and self-absorbed sidekick. Plumly is, however, attentive in giving the glorious Lamb his due. Drunkenly interrupting an awkward encounter between a bewildered Wordsworth and a blundering chap called Kingston in the middle of the dinner, Lamb insisted on fondling Kingston’s face, “inspecting his phrenological development” and singing “hey diddle diddle” at his every stupid utterance. And it is Lamb’s cheery intelligence and geniality that makes you most wish you’d been at the dinner, rather than plodding through this leaden account of it.

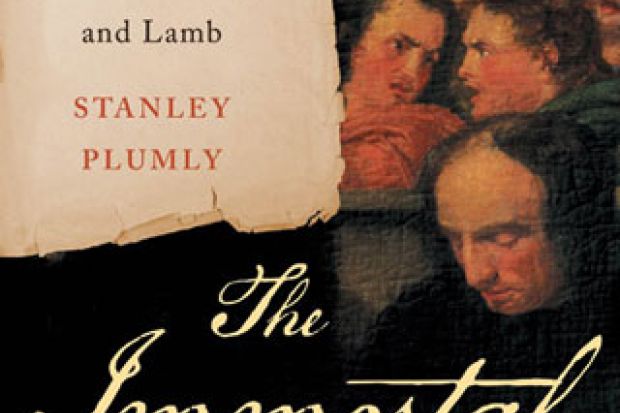

The Immortal Evening: A Legendary Dinner with Keats, Wordsworth, and Lamb

By Stanley Plumly

W. W. Norton, 336pp, £18.99

ISBN 9780393080995

Published 7 November 2014