In late November, the Wellcome Collection in London announced that it was closing its permanent Medicine Man exhibition with just two days’ notice.

“When our founder Henry Wellcome started collecting in the 19th century,” the Wellcome Trust explained, “the aim then was to acquire vast numbers of objects that would enable a better understanding of the art and science of healing throughout the ages.” However, showcasing “the story…of a man with enormous wealth, power and privilege” – even one who founded a vast medical research charity – was “perpetuat[ing] a version of medical history that is based on racist, sexist and ableist theories and language”. It had therefore become essential to ask: “Who did these objects belong to? How were they acquired? What gave us the right to tell their stories?”

Many national collections, but also university-based institutions such as the Penn Museum at the University of Pennsylvania, have been asking themselves similar questions. They have gone further, asking whether some of their exhibits should be “repatriated”. That inevitably leads to another debate about who has the right (and expertise) to speak for whom – which, in turn, calls into question the whole academic discipline of anthropology.

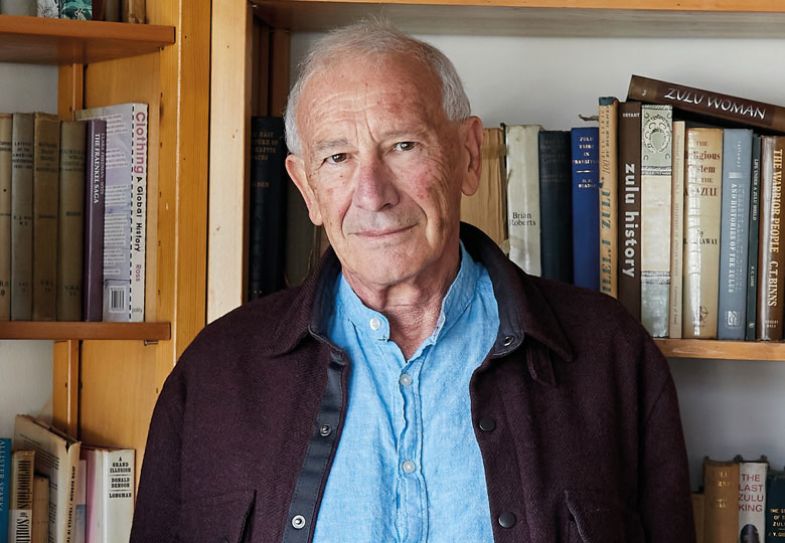

In his new book, The Museum of Other People: From Colonial Acquisitions to Cosmopolitan Exhibitions (Profile Books), celebrated anthropologist Adam Kuper uses a historical approach to explore these contemporary controversies. Now visiting professor of anthropology at the London School of Economics, Kuper recalls how he was brought up in South Africa “during the worst years of apartheid”.

“When I went to the University of the Witwatersrand [in the late 1950s], the students and a lot of faculty were very involved in politics. In my second year, there was the state of emergency: the Communist Party was banned, the Liberal Party was banned, a lot of people were put in prison without trial. And we started demonstrating. Once I was picked up by the police and held for a while,” he recalls.

Growing up in a middle-class family with three black servants, who were “part of our lives, but very distanced”, inspired an intense curiosity about “the three-quarters of the population who were disenfranchised”. He and his friends would go to illegal parties in the African townships. At university, he began to think that anthropology might provide some of the answers he was seeking.

Kuper’s aunt Hilda was herself an anthropologist. She had done two years’ fieldwork in Swaziland in the 1930s, when the country now renamed Eswatini was a British colony embedded within South Africa. When he was 18, before he went to university, she took him to a traditional village there. Soldiers served him beer in a beehive hut and a young prince, who was dressed in a toga with shield and spear but had been educated at an English public school, asked him whether he believed in witchcraft. When he said he didn’t, he was told that “there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy”.

So here was a Swazi prince trying to convince him of the value of witchcraft by quoting Shakespeare – an incident that sparked Kuper’s interest in anthropology.

After graduating, he went on to a doctorate at the University of Cambridge. He originally intended to do a PhD in South Africa, but during a visit to his homeland from Cambridge, the head of the government anthropology service told him: “Mr Kuper, you will never be allowed to do research in this country.”

“In those days, a white person needed government permission to visit and certainly to spend much time in areas that were designated for ‘non-white’ persons,” Kuper explains. “During the state of emergency [following the Sharpeville massacre of unarmed protesters by police in 1960], I had been arrested during a student demonstration. Although I was quickly released, my arrest was given a lot of publicity because my father was a High Court judge. There was a file on me, so I was effectively blacklisted.”

So he instead spent “20 months in the [Kalahari] desert living in a mud hut extremely far away from anything, mainly on my own and then with my new wife”, in what was then the British-ruled Bechuanaland Protectorate but became independent as Botswana during the course of his research, in 1966. Even then “I would be harassed when passing in and out through the South African border posts,” Kuper recalls.

He then spent three years teaching at Makerere University in Uganda but was advised to leave before Idi Amin came to power in 1971. He went on to work at UCL, Leiden University and Brunel University London, while also spending time at a number of leading US institutions and carrying out fieldwork in Jamaica and Mauritius.

Although he began his writing career with detailed ethnographic studies, Kuper soon shifted his attention to much broader questions, such as the nature of “culture”, the notion of “primitive society” and even “the private life of bourgeois England”. His celebrated 1973 survey of British anthropology is still available in its fourth edition as Anthropology and Anthropologists: The British School in the Twentieth Century.

The Museum of Other People explores the history of the great anthropological museums, which “put on display an exotic world of ‘primitive’ or ‘tribal’ peoples who lived far away or long ago”. It concludes by putting the case for the “Cosmopolitan Museum, one that transcends ethnic and national identities, makes comparisons, draws out connections, tracks exchanges across political frontiers, challenges boundaries”.

However, many progressive-minded museums still struggle, Kuper believes, to overcome their origins in very different times. One striking example is the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, which houses the vast collection of the 19th-century British army officer after whom it is named. General Rivers’ deed of gift stipulated that the material had to be displayed not only by geographical region but also on what Kuper describes as “the typological-ideological lines” that Rivers had developed based on the theory that “ideas and techniques…advanced exactly as natural species evolved” and “could be classified in the same way”.

Despite additional explanatory material, the basic arrangement remains in place, even though no one any longer believes its underlying assumptions. What this means, Kuper tells Times Higher Education, is that the Pitt Rivers Museum “still shows us the way the world looked to 19th-century evolutionist collectors”. And while that has some historical interest, “it’s as crazy to me as if you had a [Christian fundamentalist] exhibition titled ‘The world before the flood’.”

There is an ongoing debate about the precise extent to which the deed of gift permits any rearrangement, but for his part, Kuper would like to see “a permanent exhibit on Pitt Rivers and his collection, setting out his life history and intellectual influences, and showing how the collection was arranged to illustrate – inculcate – a particular view of history and evolution. Then there should be particular exhibits to show (and discuss) changing fashions for representing exotic peoples and practices.”

Such a contextualising approach could even allow the reinstatement of the collection’s exhibit on the “treatment of dead enemies”, Kuper says, which infamously included various shrunken human heads collected by South American tribespeople as trophies – until they were removed in 2020 after an ethics review. He also suggests that “a large number of exhibits should be temporary, thematic, perhaps curated by visiting scholars from Africa, South Asia and South America, and often including exchanges with other museums”.

On the issue of repatriating objects acquired by museums during colonial times, Kuper points to a number of concerns. It is often unclear or disputed to whom they should be returned if they date back to well before the creation of today’s independent states. And there are also questions about what happens to them once they are “back home”.

In the case of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum, Kuper points out, “the main thing that’s been returned was a large Tlingit totem pole from Alaska”. This has apparently been placed at an isolated site and left to decay, replaced in the museum by a newly commissioned work. So the original pole, reflects Kuper, was just “sent back to be destroyed…That seems to me an example of a mindless so-called repatriation, which ends in the destruction of a beautiful, rare, important object – for whom? Were the local people who claimed to have a Tlingit identity polled about what they would like to happen? It was a small group of identity politicians who ran this drama.”

Alongside the fate of particular objects, there are also broader questions for anthropology as a discipline. Since the 1960s, as Kuper puts it in an unpublished article, African intellectuals have argued that “anthropologists stigmatised Africans as primitive, sided with traditional rulers against the educated urban population, and generally did what they could to prop up colonial rule”.

To some extent, he accepts this critique. British administrators in Africa tended to be at best ambivalent about “the educated urban elite” and to see the continent as “divided into distinct tribal groups with ancient historic local identities and their own chiefs”, who were often supported by the colonial authorities. Anthropologists of the time often adopted a similar perspective, treating the places they were studying as “more or less closed societies” and paying little attention to “external inputs and outputs”.

Yet this is a distorted view of reality: even isolated Pacific islands are not completely closed to outside influences – and Swazi princes, as Kuper learned early on, are no strangers to Elizabethan drama. He therefore has little time for the notion of “cultural appropriation”, since “human history is all about movements of ideas and populations and languages, sometimes oppressively and sometimes on the basis of interaction and exchange”. What is far more unusual, his new book suggests, is “successful resistance to foreign influences, however heavily policed. The myth of one person, one tribe never made much sense.”

Like the other social sciences, Kuper admits, anthropology did once buy into the idea of a “primitive” stage of social development, before feudalism and then industrial modernity. For the past half-century, however, this idea has been rejected as “both offensive and ridiculous”, not least because it “had a very strong racist connotation built into it”.

There are no grounds for believing in the existence of “a distinct category of ‘primitive people’”, Kuper insists, and “anyone who is put into this category is going to be rightly offended”.

More generally, he feels that the links between anthropology and colonialism have been overstated. When he was growing up in South Africa, there were indeed anthropologists writing in Afrikaans who worked hand in glove with the government to prop up the apartheid regime. But the English-speaking anthropologists he has known were generally “pretty left-wing”, noting that his aunt was a communist.

At the very least, these liberal anthropologists were “committed to reform” even if they were not “active critics” of the regime in which they lived, he adds. “Very few of them were there to further the aims of the British Empire,” he insists. Furthermore, they often studied topics of no interest to administrators, such as “breakaway Christian sects”, and were seldom asked by policymakers for advice.

Kuper is wary of what he sees as “a connection between the postmodernist movement and the indigenous people’s movement”, in their pursuit of progressive goals. “They both have the idea that you can only understand something if you come from within it yourself,” he explains. “But this whole set of ideas is then given a kind of moral and political force in the postcolonial critique of scholarship. I think this has understandable ideological and historical roots, but I don’t think it has any intellectual weight.”

As a specific example of what he objects to, Kuper’s book cites “an article of faith in the international indigenous people’s movement that shamans have a special insight into the origin, ownership and powers of certain artefacts” – a belief that some museums do their best to accommodate. Mexican shamans visiting the Berlin ethnographic museum were consulted about some of its exhibits, and a Masai spiritual leader was invited to give guidance to the Pitt Rivers Museum, he explains. The latter visit, in 2020, resulted in the museum agreeing to repatriate five artefacts whose presence in its collection was deemed problematic. The museum’s curator of world archaeology, Dan Hicks, is a strong supporter of repatriating objects, as set out in his 2020 book The Brutish Museums.

However, Kuper’s book is dismissive of deference to tribal leaders. “There cannot be many curators in Europe who would support the invigilation of an exhibition of Islamic art by fundamentalist mullahs,” he writes. “Do any Oxford museums insist that only a clergyman may curate a display of medieval Christian art and artefacts? Yet some respectable institutions go along with the equally questionable doctrine that only people with an ancestral relationship to a particular precolonial cult are entitled to say what it is all about.”

What “cannot easily be defended”, as Kuper puts it, is the idea that “human beings can’t understand each other unless they have some kind of racial or ancestral claim to a particular kind of knowledge or a visceral physical understanding of what it’s like to be a particular kind of person.” For all the charges of white privilege that such a stance could elicit, Kuper is adamant that such claims must be challenged. “I don’t think the argument stands up,” he says.

In other contexts, Kuper suggests, we tend not to believe that cultures are completely impenetrable to outsiders. He has elsewhere compared anthropologists to immigrants, who may have little initial knowledge of a society but often manage to learn its language and codes, discover how to operate within it and build successful lives. The idea, for instance, that immigrants to England can never become “truly English” tends to be confined to extreme right-wingers and racists, he says.

Moreover, the notion that the understanding of insiders is always deeper than that of expert observers is nonsense, he continues. “It would be absurd to suppose”, he writes, “that your average Londoner understands more about her city, its history, its ethnic complexity, its informal customs, than a qualified researcher who might come from Paris, or Bombay, or Singapore, and whose findings are tested by scholarly criticism of sources, methods and logic,” he claims. “We do need experts”, he continues, particularly those who can bring “a sense of history, a comparative perspective, a broader angle of vision to enrich the appreciation of human interconnections”.

Traditional anthropological museums incorporated many questionable and offensive assumptions, which have now been rightly rejected. But Kuper’s book makes the case that we should not throw out the baby with the bathwater by also rejecting the very idea of anthropological expertise.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Collections and objections

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?