As a geographer, it was only when she lost the ability to read maps that Jenny Pickerill finally admitted to herself that something was seriously amiss.

This was despite the 30-page risk assessment that she had submitted to the University of Leicester for approval before setting out for the remote Kimberley region of northern Western Australia to interview indigenous environmental activists. It listed all manner of potential horrors, such as extremes of weather, encounters with poisonous snakes and man-eating crocodiles, collisions with wild cows and kangaroos and, most pertinently, a forbidding array of tropical diseases, including the one with which she was ultimately diagnosed.

The university had followed standard practice and checked the Foreign Office’s list of dangerous destinations. Not finding Australia there, it was happy to sanction the four-month trip and Pickerill – an adventurous soul with previous experience of remote regions – successfully applied for a British Academy grant to fund it.

“I am really interested in grass-roots alternatives to industrialisation and capitalist solutions to problems,” she explains. “The Kimberley is an area that is quite untouched in lots of ways but it is a target for the Australian government as a place for resource extraction. I was interested in what indigenous environmental activists were proposing as alternatives to large-scale mines and gas plants.”

Her grant paid for her airfare but not much more: a research assistant and hire car were beyond her means. Hotels would have been, too, if they had existed in the far-flung villages Pickerill was planning to visit. But a close friend, the artist Naomi Hart, agreed to accompany her and, in a “random act of generosity”, a relation of Hart’s brother’s friend agreed to lend her a tent and a rusty Toyota Land Cruiser (popularly known in Australia as a “troopy”).

Although she took a satellite system capable of sending out an emergency distress beacon from anywhere in the world, Pickerill – who is now professor of environmental geography at the University of Sheffield – was grateful for Hart’s presence since she didn’t entirely trust the troopy not to “break down in the middle of a river crossing”.

“I had travelled with Naomi before: she did some research with me when I was a postdoc in Australia many years ago and, because she is artist, she doesn’t seem to mind traipsing over the landscape while I collect data,” Pickerill explains.

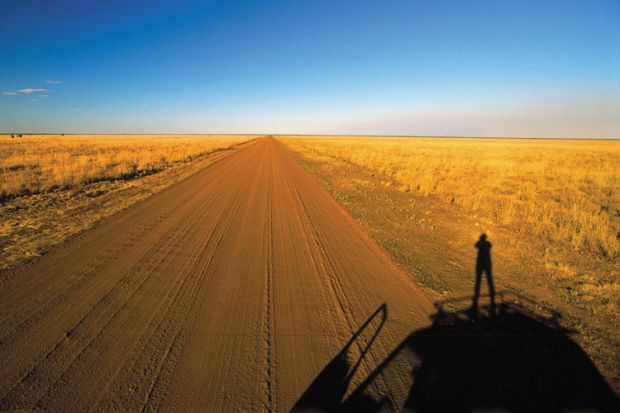

After a week-long 1,900 mile drive up from Perth, Pickerill and Hart arrived in the Kimberley in March 2011. Pickerill’s work was tiring and stressful: “Tracking down interviewees in the outback and trying to convince people in the middle of a land rights protest to talk to me was difficult.”

Camping every night only added to the strain and Pickerill admits that “there were certain moments when I thought: ‘What have I done? I am living out of a truck in the outback and I could really do with a shower.’ ”

For this reason, when, about three weeks into the trip, she first started to become forgetful and vague, she put it down to nothing more serious than excessive fatigue – and she rather enjoyed the feeling of being “really calm and mellow”.

“But after a few more weeks I could not remember what my research was on,” she says. “I carried on working but forgot to write any notes, and my interviews got shorter and shorter as I no longer knew what I was asking or what I was doing. I just wanted to curl up and sleep. I slept more and more and found I could fall asleep anywhere, even in the shower or walking along a path.”

It was only when her basic geographical faculties began to crumble that she – and, in particular, Hart – “realised we were in trouble”.

“I was meant to be map-reading but I was silent. Naomi asked where we were going and I said: ‘I have no idea: I don’t know where we are.’ This was completely out of character: I have always known where I am and how to get home. Now I just saw a jumble of lines on a piece of paper.”

But she still refused to see a doctor in the Kimberley, fearing that she might be ordered to abandon Hart in the middle of a “very male outback environment dominated by mines”. Hence, she insisted on helping her friend return the troopy to Perth – even though, by that stage, she was capable of no more than 30 minutes of driving a day.

“Naomi did everything: drive, set up camp, get food, fix the truck. If she had not been there I would probably still be out in the bush, having a sleep on a rock,” Pickerill says.

When, a “fraught” week later, they finally arrived back in the state capital, Pickerill was diagnosed with Ross River virus: a mosquito-borne affliction that, while not deadly, can last for a number of years and potentially leave sufferers with chronic fatigue syndrome.

“Although I had most of the symptoms – painful hands, feet and jaw, exhaustion and migraines – the biggest impact was on my memory,” Pickerill explains. “I still have little recollection of what we did in the Kimberley or of what I did the following year.”

As the condition worsened, she eventually even lost the ability to speak coherently. “When searching for words, I could only get to something that sounded like – but wasn’t – what I wanted to say, like ‘carpet’ instead of ‘car park’. I felt incredibly stupid – but then promptly forgot that I was frustrated.”

After six months on sick leave, she returned to Leicester on a part-time basis and even took up lecturing again. Although she was still struggling to recall words, she “got good at improvising and replacing words I could not entirely remember with simpler terms. It probably helped the students; I could not pretend to be too clever because I could barely remember what I was trying to teach,” she says.

But writing remained beyond her for more than a year, since she “couldn’t hold a thought in my head long enough to turn it into a good sentence and write it down”. She was also troubled by an email she received from an indigenous activist saying that his own case of Ross River virus had laid him low for five years.

“I thought it was the end of my academic career,” she admits. “I knew there was no way I could stay a partial academic for that long. It wasn’t what I wanted to be: I don’t like half doing things. I had this vision of being permanently asleep. How could I be an academic if I couldn’t think? But I had brilliant colleagues, who joked that lots of people had pulled off being an academic without thinking. That cheered me up and made a huge difference.”

After about 18 months she began to become fairly adept once more at coping with the everyday demands of her job – even managing to successfully apply for her chair at Sheffield. But her ability to recollect what she had recently done took longer to improve, and it was not until last year that she was declared fully fit again: a verdict with which she concurred after passing a self-imposed test and successfully running an “incredibly tiring” student field trip to the US.

But she still doesn’t recognise many of the places depicted in Hart’s paintings of the Kimberley, which the artist exhibited once they were back in the UK. And she is struggling to write up the work she did there even before her notes became incoherent.

“I feel like I am diving into the dark of somebody else’s data: it is very odd,” she says. “I have interview recordings and am using my photographs to try to piece together what I did. But it is far from ideal, and I told the funder that I would not be able to deliver on all research aims.”

Then there is the blow her experience has dealt to her confidence about further travel – especially in mosquito-infested regions. She can’t get Ross River virus again, but she could get a similar infection called Barmah Forest virus – plus a “long list of other stuff”, some of which were included in the two pages she added to her risk assessment of the Kimberley while she was out there.

“There was just so much that could have gone wrong and killed me,” she says. “I don’t think people expect it of Australia: they think it is developed, but when you go off the beaten track it isn’t.”

For this reason, she has promised her family that she will not return to the Kimberley. She also recently declined to accompany students on a field trip to Kenya “because I have a fear of being sick in a difficult environment”.

But that wariness makes her feel “a bit of a lightweight” in a discipline that attracts adventurous types, many of whom actively seek out remote and extreme environments.

“Part of what we [geographers] are looking for is places others haven’t reached and understood. It is not so much exploration in the old-fashioned geography sense because that was about conquering places: this is about understanding all the diversity of the world,” she says. Geographers are expected to “have the courage to go out to those places and cope with things” and Pickerill believes that the opportunity to acquire hair-raising stories is “part of what people find exciting about the discipline”. “At Sheffield they do a lot of work in the Arctic and have to cope with polar bears: it is part of the talk and bravado about going there,” she adds.

But she does not think that that culture needs to change. She would not want universities to become more “controlling” over where they permit their geographers to go, and she is determined to build up her confidence again so that she can have more adventures of her own.

Avoiding tropical travel would render her unable to capitalise on the many useful research links she has built up in countries such as Australia and Thailand, she points out, as well as closing off many potential future avenues of research into people “creating alternatives in the out-of-the-way margins of society”.

“I regret getting ill in Australia but I don’t regret going,” she insists. “My frustration is that I am slightly wavering on having the courage to go again.

“I want to be the person who goes out and finds all these interesting things in difficult places. It is my research and what I am passionate about – and I don’t want to spend the rest of my life at a desk.”

One option was to consult a doctor in the Kimberley. But that would have involved driving out of her way to one of the region’s few towns and, even in her barely functional state, she was still reluctant to let go of her research. “Academics can be really stubborn about completing projects,” she says.