Many an evening, Michael Baron Poliakoff undertakes the rush-hour slog from his downtown Washington DC office to the suburban campus of George Mason University for the sole purpose of creating more thoughtful and reflective people.

The adjunct faculty member accomplishes that task by exploring with GMU undergraduates such stories as the Oresteia, Aeschylus’ trilogy of plays based on the ancient Greek myth of murderous family dysfunction in the wake of the Trojan War, and Virgil’s Aeneid, a neo-Greek paean to Roman exceptionalism that depicts the Empire as having been founded by descendants of a Trojan hero.

A main argument for delivering refinement through Classics, for Poliakoff, is that ancient Greece and Rome are widely regarded as the cradle of Western civilisation, with achievements in art, literature, philosophy, engineering and law that became models for what followed.

Another argument, according to a worldview for which Poliakoff is a chief promoter, is that a classical education confers a badge of mental supremacy on account of its requirement for students to master Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics majors are rare for the same reason that physics majors are, according to Poliakoff, whose day job is as president of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, a politically conservative group that offers advice to institutional governing boards. Both disciplines require “real sweat and effort”.

A degree in Classics is “very good for the mind. It’s cognitively enriching. It’s a gateway into fantastic texts of history and literature. But it doesn’t come on the cheap. It doesn’t come easy.”

For many other figures in Poliakoff’s field, that is an increasingly problematic outlook. Studying languages can be important, says Shelley Haley, president of the Society for Classical Studies, the chief North American scholarly association focused on Greek and Roman civilisation. But Classics scholars must recognise and reject “the privilege and power that accrues to the chosen few deemed worthy to study the field”, adds Haley, the society’s first black female leader.

Higher education is one of Western society’s most enduring institutions, and teaching Classics was instituted from its beginnings in the Middle Ages. But now, like so much else around it, Classics is under pressure from both the economic ruthlessness and the ideological restlessness of modern civilisation.

As measured by the numbers, Classics’ traditional guardians, such as Poliakoff, appear to be losing ground. Less clear, though, is how much of the field will be left for anyone if Classics scholars can’t agree on a new vision that unites universities, students and employers.

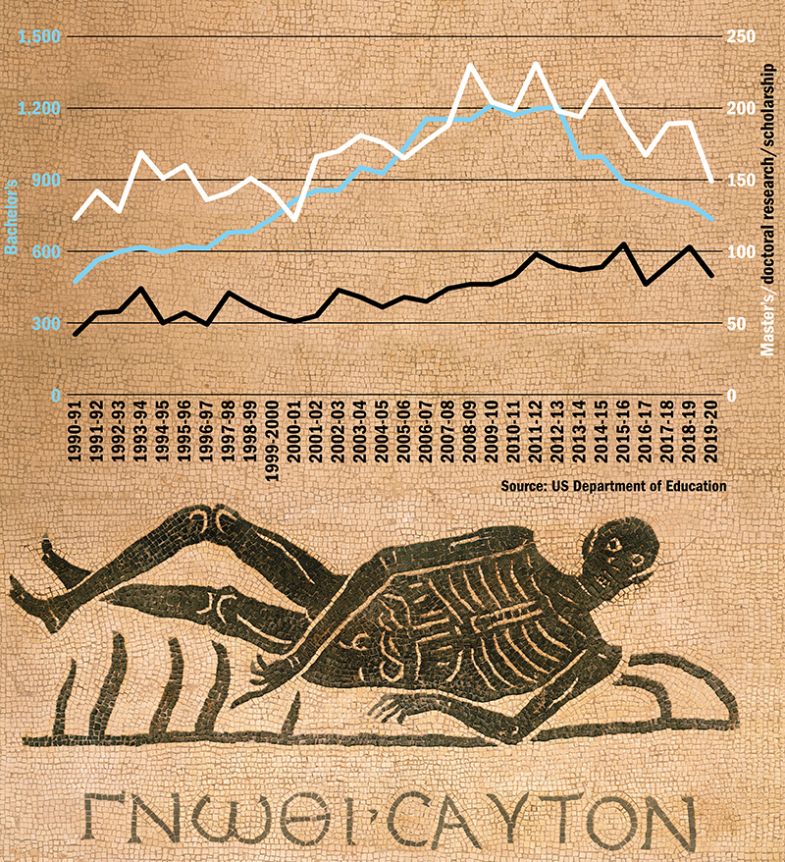

Annual US production of undergraduate degrees in Classics has fallen steadily, from more than 1,200 in the 2012-13 academic year to 736 in 2019-20. Over a similar pre-pandemic time frame, the total number of institutions with a Classics major or department shrank by more than a dozen. Earlier this year, Howard University – one of the nation’s premier historically black institutions and the only one with a Classics department – joined the list of those eliminating them.

Furthermore, of the top 25 books assigned each year by college professors, as measured by the Open Syllabus project, Classics has fallen from a typical level of six in the late 1990s to just two in recent years.

Yet in other ways, Classics keeps showing its remarkable resilience, both on college campuses and in broader US culture. The television series Lost, the Percy Jackson adventure novels, and the Assassin’s Creed Odyssey video game are among recent popular cultural outputs that draw heavily on the classical tradition.

On college campuses, that enthusiasm manifests itself in mythology classes that can enrol hundreds of students at a time. Rebecca Futo Kennedy, an associate professor of classical studies at Denison University, was one of 1,800 students on the ancient mythology course she took as an undergraduate at Ohio State University, for instance. “In terms of the material, Classics is actually, in many ways, more popular than ever – with students, with the public. Mythology is everywhere,” says Kennedy, who also teaches environmental studies and women’s and gender studies.

But while there are still many students who want to major in Classics, they are often deterred by tuition-paying parents, who feel it won’t set them up for a viable career, Kennedy observes.

Classics degrees awarded in the US

Alongside the economic reckoning posed by such employability concerns, teachers of Classics are being confronted by sociopolitical challenges related to the field’s complicated racial history.

One of the more succinct summaries of the problem comes from Kwame Anthony Appiah, a professor of philosophy and law at New York University. He has mocked the imaginary vision of a “golden nugget” – the idea that human civilisation’s most perfect form arose in ancient Greece and spread west. It is a perspective that suggests fawning reverence for Graeco-Roman history and its languages, rather than objective study of them. And the result, some scholars believe, is a complicated brand of pro-European cultural racism wrapped in an academic cocoon of plausible deniability.

Traditional classical studies “is really, really hard to disentangle from white supremacist structures in the world”, Kennedy concedes. For centuries, she and others note, the written records of ancient Graeco-Roman life have been selectively deployed to justify colonialism, empire-building, African enslavement, Jim Crow laws and modern-day class and racial and gender hierarchies.

“This thing we called the Classics is a packaging of the ancient world in a very specific way,” Kennedy says. “And that specific way has been, for two centuries at least, a packaging for and by wealthy elite classes of European descent in the promotion of their own superiority and values in the world.”

Dan-el Padilla Peralta, an associate professor of Classics at Princeton University, has won popular attention for bluntly suggesting that the discipline of Classics in its traditional form appears almost perfectly designed to minimise the value of black intellectual life. “Systemic racism is foundational to those institutions that incubate Classics and Classics as a field itself,” he recently told The New York Times.

On the other hand, Howard’s decision to shut its Classics department has been painful for some black scholars. In a Washington Post article in April, Cornel West, a renowned academic voice for black equality then at Harvard University, called Howard’s decision a “spiritual catastrophe”. Using language similar to that of the traditional-minded defenders of Classics, West called Howard’s move another marker of moral decline and intellectual narrowing in American culture.

Howard blamed its decision on a lack of student interest and a desire to emphasise “teaching with practical application”. In that regard, one of Howard’s big academic priorities these days is the teaching of cybersecurity skills.

The decline of Classics, then, is just another chapter in the tough story of mercenary woe for the humanities. Universities are sacrificing educational approaches with proven long-term value to students and society because many companies and the politicians they fund judge universities largely on the basis of initial job placements.

There is, to be sure, some hope that conditions for the humanities will improve once the pandemic retreats and the resulting financial pressures ease. But the numbers have been stark since long before Covid-19 appeared. The humanities accounted for only 10 per cent of US bachelor’s degrees in 2018, down from nearly 15 per cent in 2009, according to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Over that same period, engineering’s share of total degrees rose from 7 per cent to 10 per cent, and health and medical sciences expanded from below 8 per cent to more than 12 per cent.

On the other hand, losing a departmental structure might bring some advantages for Classics. At the University of Kentucky, former Classics department staff who have been absorbed into a larger foreign languages department describe themselves as popular with colleagues because their high-enrolment classes, such as mythology, help to offset a contraction in student sign-ups for language courses generally.

Such situations underline the importance of emphasising course enrolment numbers, rather than just majors, in measuring student preferences. Even more fundamentally, Denison’s Kennedy says, faculty must patiently explain – and administrators must hear – the need to prioritise the overall life of students and institutions.

Princeton stands as an example. In announcing the removal of the language requirement from its Classics major earlier this year, the department explained that it had acted upon its students’ feeling that the requirement “acts primarily as a deterrent” to potential Classics majors. “An approach based on inclusion and persuasion will be more effective in encouraging language study than one based on compulsion,” the department said.

The university specifically identified the change as matter of promoting racial equity. “Having new perspectives in the field will make the field better,” explained Josh Billings, a Princeton professor of Classics and director of undergraduate studies in the department.

But some dismiss that stated motivation as flawed. John McWhorter, an associate professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University, accused Princeton of concluding that the Greek and Latin languages are too difficult for black students to learn. And Princeton’s move, Poliakoff says, will cost its graduates in the job market because teaching Classics without the language requirement has “taken the discipline out” of the subject.

Poliakoff is a Rhodes Scholar with bachelor’s and doctoral degrees in Classics from Yale University and the University of Michigan respectively. With multiple universities now dropping their language requirements, he says, Classics risks becoming “much more concentrated on the things that have now become sort of buzzwords on social issues – racial justice, and so forth – in the ancient world. All of which are quite interesting and important things, but don’t cut the roots out from under the tree and expect that the tree is still going to bear fruit.”

Poliakoff perceives that companies in a variety of industries are still perfectly happy to give hiring preferences to Classics graduates. But it must be a strong Classics degree, he argues, which includes language proficiency. "When young people are getting on the job market and competing with a weak humanities degree against those who have a technical degree, they’re going to have problems,” he says. And Roosevelt Montás, a senior lecturer at the Center for American Studies at Columbia, notes that while companies publicly say they value the teaching of the traditional Classics and other humanities, they don’t truly advocate for it. Students see “a disconnect between what employers and industry leaders say that they want and what actually is happening on the ground in hiring,” he says.

Norman Sandridge, an associate professor of Classics at Howard, is trying to bridge that gap. He works with a colleague at Tulane University in New Orleans to run Kallion, a non-profit organisation that aims to teach leadership skills using insights from the ancient world.

People of the ancient world did not have the benefits of widespread public education or an independent media to expose wrongdoing, Sandridge explains. As a result, they were taught to watch carefully for signs of antisocial behaviours – which could be detected even during childhood – in their potential leaders.

The enduring need for that skill was made clear this past January, says the Society for Classical Studies’ Haley, when a mob stormed the US Capitol aiming to overturn the presidential election. Some observers, including Princeton’s Padilla, noted the classical trappings among the insurrectionists, many of whom were white supremacists; one example was a Greek helmet with “TRUMP 2020” written on it.

But for Haley, emerita professor of Africana studies at Hamilton College in New York State, the insurrection was a confirmation that the democracy that first arose in ancient Athens is more fragile than many people assume. In that sense, Classics should be seen “not as a glorification of Western civilisation, but as evidence that humans are not hard-wired for democracy, equity or justice”, she says. “Those things have to be guarded and protected from autocrats.”

Other Classics academics whose work addresses major modern concerns include Clara Bosak-Schroeder, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who sees the ancient Greeks as models for caring about the natural environment from a self-interested perspective rather than an altruistic one.

Another, Yale professor Joseph Manning, has done work highlighting the previously unappreciated impact of climate-related shifts. For instance, he argues that the eruption of Alaska's Mount Okmok in 43BC resulted in crop failures that played a central role in the power struggles that created the Roman Empire.

Such work helps to underline the need, acknowledged by many in the field, for Classics to undergo its own revolution. Haley, for instance, thinks that the antidote to Classics’ formation “in the crucible of white supremacist patriarchy” is to emphasise that ancient Greece and Rome are only part of a continuum of human history marked by racial and economic oppression and attempts to fight against it. And, to that end, she advocates a rebrand for the discipline.

“It makes absolute sense to teach about the language, culture, politics and social history of the ancient Mediterranean,” she says. “But don’t call it ‘Classics’ as if there is something superior and essentialist about the ancient Mediterranean.”

The University of California, Berkeley’s Classics department, for instance, has renamed itself the department of Ancient Greek and Roman studies. Others have kept their names but broadened their focus. Stanford University’s department now gives ancient China a level of attention similar to that it pays to the Roman Empire.

Classics departments also suffer from the general problem across the humanities of producing more doctorates than they can employ. Between 1990-91 and 2019-20, the number of Classics majors in the US rose by 55 per cent to 736, while the number of doctoral graduates rose by 98 per cent, albeit to the still small figure of 83. Moreover, while bachelor’s graduates declined nearly 40 per cent between their peak in 2012-13 and 2019-20, the number of doctoral degrees has largely held steady.

Over the long term, universities may be driving down interest in their own Classics programmes by refusing to hire enough of their graduates to teach in them, according to Simeon Ehrlich, who earned his doctorate at Stanford and is now an assistant professor in Classics at Concordia University in Canada. “They are eager to train graduate students but unwilling to provide them the opportunities they have trained them for,” he says.

Doctoral graduates may also be diminishing their job prospects by dismissing teaching positions at secondary or elementary school levels – the source of future Classics majors – as a lesser option, says Helen Cullyer, executive director of the Society for Classical Studies.

“The gold standard has been the tenure-track job,” Cullyer says. Yet grade-school teaching is “another important career, and shouldn’t be seen as second-class employment”.

A new genre of specialised high schools and pre-college programmes are reviving the teaching of Classics. Montás and Padilla teach one together in New York City. It goes beyond ancient texts to include the Enlightenment era and the central writings of US history, and it is aimed at high school students from low-income families. Yet the bulk of US grade schools serving such students struggle to provide high-quality offerings in the humanities, with many cutting all but the most basic elements of their curricula.

“It’s very squeezed and impoverished,” Montás says. Classics was long the domain of the nation’s elite, “and what we have now is a kind of a receding of the tide to its traditional watermarks”.

US higher education compounds the student supply problem by focusing unduly on metrics, Sandridge says. Humanities do make major contributions to the emotional intelligence of students, he says, but those kinds of value defy easy assessment: “Higher ed has kind of written itself out of the business of working on these things because they don’t fit the model of how you exactly measure them.”

Some institutions are trying to do better on incentivising the study of humanities. Mallory Monaco Caterine, a professor of practice at Tulane and co-leader of Kallion with Sandridge, cites a Tulane initiative that guarantees medical school admission to students who earn high grade-point averages in a humanities programme as long as they meet basic pre-medical requirements. It’s a way of recruiting medics with greater cultural competency, Monaco Caterine says: a move that other institutions would do well to mimic in a nation whose scientists have developed multiple vaccines to end a deadly pandemic but can’t figure out how to convince enough people to take them.

Howard, meanwhile, may be getting its own lesson on those kinds of trade-offs. It was recently forced to shut classes for several days because of an increasingly common problem in higher education and beyond: a ransomware attack.

For all the focus that Howard and many other US universities have been putting on cybersecurity as a hot new career option, many real-world battles are being lost. That is reflected in the fact that resolving such attacks often boils down to the decidedly unsophisticated tactic of buying insurance to cover the ransom payments demanded by the hackers to remove their blocking software from the computer systems they’ve infected.

While Sandridge waited for the network to come back up at Howard, he noted that the word “cyber” derives from the Greek “kubernetes”. It means helmsman or pilot and is often used metaphorically to refer to any kind of leader, “especially a planful one”, Sandridge says. The lesson he derives from that is that computer security, like many other human endeavours, needs a more thoughtful approach.

“How can you have good cybersecurity”, he asks, “without planful leadership that is informed by philosophy and the other humanities?”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?