In 1925, the Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn announced that he was about to embark on a trip to Vienna, in the hope of securing a meeting with Sigmund Freud. The motor-mouthed impresario – whose personal formula for the ideal movie was to begin with an earthquake and build to a climax – expected psychoanalysis to provide studio writers, actors and directors with a blueprint for bringing “genuine emotional motivation and suppressed desires” on to the screen, and he hoped to lure Freud, “the greatest love specialist in the world”, to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with an offer of $100,000.

Sadly, Goldwyn never secured an invitation to Vienna’s 19 Berggasse. Besides having little to no interest in film, Freud was deeply unhappy about the way in which his work had been bowdlerised and stripped of its sexual components by American purveyors of popular psychology. “FREUD REBUFFS GOLDWYN” lamented The New York Times, after Goldwyn’s overtures were rejected.

Film and psychology were already deeply connected. When the first motion pictures were projected at the Grand Café in Paris, in 1895 by the Lumière brothers, American and European universities were equipping their psychological laboratories with a raft of instruments to study the mechanics of perception and visual recall. A decade on, the American cinema found itself at the vanguard of what an early history of film by Terry Ramsaye, A Million and One Nights, called the “simple, primitive and universal language of the pictures”. A chorus of commentators began to wonder if the movie industry was becoming, in the words of the critic and novelist Francis Hackett, “the greatest instrument of popular suggestion that has ever been devised”. Even more worryingly, German opponents of early cinema warned that, as one prominent psychiatrist had it, “mere habituation to the darting, convulsive, twitching images of the flickering screen slowly and surely corrodes man’s mental and, ultimately, moral strength”. Vertigo, insomnia and most of the symptoms associated with hysteria and neurasthenia had, apparently, already found a home in the half-light of the movie theatre.

As questions over the social and psychological impact of the cinema intensified in the early 1900s, Harvard psychologist Hugo Münsterberg was encouraged to give his thoughts on the medium. Having previously dismissed “the pictures” as no more than cheap entertainment, Münsterberg, at this time America’s leading academic psychologist, had a change of heart. The working-class Americans whose five cents granted them admission to The Great Train Robbery (1903), the mobs of unruly youngsters who raised the roof at the knockabout comedy Catch the Kid (1907), were, he believed, engaging with a technology that had grasped the means of controlling their memories, perceptions and emotions. Film’s great breakthrough was, Münsterberg contended in his 1916 book The Photoplay, to make the inner workings of the mind visible; it was a new way of thinking – about thinking.

Münsterberg’s ruminations earned him an invitation to Paramount, where he would develop a series of psychological features for its “virtual motion picture university”: its short-lived venture into educational releases, which was to have been a kind of Open University minus coursework and qualifications. But the major studios were not destined to maintain a lasting relationship with academic psychology. Goldwyn’s promise to bring psychoanalysis to the screen was eventually made good by a raft of thrillers and dramas – such as Now, Voyager (1942), starring Bette Davis, and Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), which provided many Americans with their first introduction to the vagaries of dream analysis and the talking cure. But the unfortunate side-effect of this lasting infatuation was that film-makers would for too long ignore the wayward experiments and dramas that engulfed other schools of psychology, particularly social psychology, in the 1960s and 1970s.

Michael Almereyda’s 2015 film Experimenter, which will be released on DVD in the UK on 8 February, revisits the most infamous of all social psychology experiments. It opens in August 1961, with Stanley Milgram (Peter Sarsgaard), a 27-year-old assistant professor at Yale University, watching as his volunteers are ushered into a fake learning experiment that will require them to follow orders to issue electric shocks to “learners” in an adjacent booth. The experiment is a scientific short-con: the shock-generator that sits in the teachers’ booth is an empty metal box; the volunteer in the adjoining room is an actor.

For Milgram, this deception is merely “a technical illusion” that will allow his “obedience to authority” experiment to prove that “it is not so much the kind of person that a man is as the kind of situation that he finds himself in that determines how he will act”. To this end, all the volunteers are urged to follow protocol, disregarding the shrieks and protests of the unseen “learner”. Milgram, a Brooklyn-born Jew who has been following the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, suspects that many will obey orders to issue the potentially lethal maximum 450-volt shock, showing that the “banality of evil” functions by chain of command.

Contrary to the expectations of Milgram’s psychiatric colleagues, two out of three of the men and women inducted into his bogus experiment go on to administer the maximum shock. While the results of the elaborate hoax, played out in different versions over two semesters, appear to confirm Milgram’s assertion that “the kind of character produced in America can’t be counted on to insulate its citizens from brutality and inhumane treatment in response to a malevolent authority”, the results are immediately contested by colleagues, who feel that Milgram has abused his position, betraying the imperative principles of transparency and openness. Among the detractors is his former supervisor at Princeton University, Solomon Asch, who complains that the experiment has given him “a dirty feeling”.

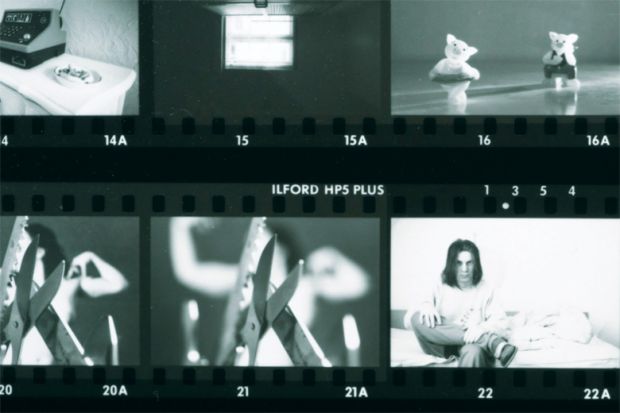

Almereyda’s muted portrait of Milgram has a few disconcerting tricks of its own. As well as having Milgram sometimes speak directly to camera (as the psychologist did in several educational documentaries), Almereyda employs overblown black-and-white photographs as surrogates for actual locations outside of campus. Stranger still, at one point an elephant, unseen by all, wanders into the laboratory. These moments of whimsical artifice chime with the tricksterish sensibility that Milgram brought to all his experiments, but Almereyda’s studiously quirky biopic fails to deliver on another count. Although Experimenter is alive to the cultural reverberations of the obedience experiments, it consigns the most telling objection to Milgram’s deception to one fleeting moment in which he informs a class of students that president John F. Kennedy has been assassinated. The incredulity of one student – her suspicion that the announcement is false and part of a new study – is perhaps the real legacy of Milgram’s experiment. After that, how many campus volunteers would take the purpose of a psychology experiment at face value? And how would this epidemic of distrust and second-guessing compromise research objectives? In my view, social psychology did itself untold damage by its serial reliance on laboratory deception in the 1950s and early 1960s because the tactic meant that its findings were based on what the Harvard ethicist Herbert Kelman called “an unspecifiable mixture of intended and unintended stimuli that make it difficult to know just what the subject is responding to”.

Although the critics of deception in psychology experiments proposed that role-playing could provide a viable alternative to the complex deception that Milgram and others had orchestrated, another 2015 film, Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s The Stanford Prison Experiment, shows that a different set of dangers and pitfalls attended any invitation to make-believe. The film, which has not yet been released in the UK, is set in the summer of 1971, when Philip Zimbardo, a high-school friend of Milgram, recruits 24 male students to participate in a simulation of prison life at Stanford University. Randomly separating the volunteers into guards and prisoners, but informing each that their selection rests on personal traits identified in tests and interview, Zimbardo believes that, in his mock-up environment, the rituals and protocols of real prisons will, over the course of two weeks, be internalised to the point that volunteers will actually forget that they are simply volunteers. If all goes to plan, Zimbardo, in his double role as prison warder and observer, will garner strong evidence to demonstrate how “situations can have a more powerful effect over our behaviour than most people appreciate”.

Alvarez traces the ensuing drama – think Lord of the Flies relocated to a state penitentiary – from the moment Zimbardo’s volunteer prisoners are arrested at their homes by real police officers. Arriving at “Stanford City Prison”, we see them being stripped, deloused and given a numbered gown to wear by the uniformed guards. Hostilities commence with the prisoners being woken on the first night by guards blowing whistles. The following morning, the prisoners stage their first protest, discarding their uniforms and barricading themselves into their cells. On day three, one of the inmates, traumatised by the wanton aggression of one guard, is released and Zimbardo (played by Billy Crudup) is forced to defend his laissez-faire approach as superintendent to both a colleague and his psychologist girlfriend.

What happened over the next three days at Stanford, with the prisoners showing less and less resistance to the random abuses of three particularly callous guards, has become part of the folklore of modern psychology. When Zimbardo finally pulled the plug on the experiment after six days, he believed that he had proved exactly what he set out to. Echoing the findings of Milgram’s obedience experiment, as well as a seminal study of the transmission of aggression among children by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura, his experiment had, apparently, demonstrated the power of “situational forces” in transforming well-balanced individuals into petty tyrants. Indeed, for Zimbardo, “the mere act of assigning labels to people, calling some people prisoners and others guards, is sufficient to elicit pathological behaviours”.

To its credit, The Stanford Prison Experiment does not entirely endorse this received explanation for the guards’ behaviour. Contrary to Zimbardo’s claims, we see that the volunteers are not merely responding to institutional or environmental contingencies. On being given their khaki uniforms, their mirror sunglasses and truncheons, Zimbardo’s volunteers were being tacitly encouraged to play out a role that was most probably only familiar to them through the cinema. This is a crucial and easily overlooked point. That the most abusive of the guards in Zimbardo’s experiment chose to model his interactions with prisoners on the sadistic warden from the 1967 Paul Newman film Cool Hand Luke probably says as much about the psychological reach of the movies as it does about the “situational forces” that the experiment sought to simulate.

As the psychologist Gordon Allport observed back in the heyday of Technicolor, the cinema’s “standardised daydream”, its unending programme of swooning romances and barroom brawls, was a hotline to “the deeper, less social portion of the spectator’s unconscious life”. And this, of course, is precisely why Samuel Goldwyn had been so keen to meet with Meister Freud.

Antonio Melechi is a visiting fellow in the Humanities Research Institute at the University of Leeds.

后记

Print headline: Frames of mind

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?