If you asked UK-based researchers to name the biggest threats to British science, it’s a safe bet that Brexit would feature high on the list.

Surveys suggest that very few academics voted for Brexit, and there are widespread fears among them that exiting the European Union will deprive them of the ability to work with their European neighbours as closely as they have been doing in recent years.

The UK’s ultimate relation to the EU’s research programme is unclear at this point. It was revealed last week that the UK government wants to attain the “associated member” status enjoyed by current non-EU members, such as Switzerland, Israel and Norway. This would allow the UK to continue to pay into and participate in the research programmes. But fears remain that the EU will insist on the continued free movement of people as a condition for granting such a status, as it did in 2014 when the Swiss people voted to restrict immigration from Croatia. Since the UK government appears determined to end free movement, that may rule it out of associated membership.

In that nightmare scenario, British labs would be deprived of the large grants from the European Commission that enable them to work on some of society and industry’s biggest challenges in teams that draw on experience from all corners of the Continent. Top individual UK researchers would be unable to bid for the lucrative and highly prestigious grants bestowed by the European Research Council, or to recruit staff as easily from the Continent. And, perhaps worst of all, such conditions might lead to a brain drain that would deprive the UK of its best researchers.

But few in the UK have stopped to think about how countries across the Channel could be affected by such a change to the European research landscape. Conversations at research conferences suggest that many researchers on the Continent are as downcast by the situation as Britons, since losing the UK will affect the quality and prestige of the entire EU funding system.

But how exactly could the scientific futures of countries that have previously enjoyed a close relationship with the UK be changed by Brexit? How are they preparing for the fallout? And could some researchers and governments secretly be rubbing their hands together at the prospect of Europe’s most successful research nation pulling out of the scramble for grants in a programme whose success rate is a mere 14 per cent ?

Thomas Jørgensen, senior policy coordinator at the European University Association, predicts that if the UK was forced to drop out of the EU’s research and innovation funding system, known as its framework programmes, this would be noticeable within a year in “crude measures”, such as the impact factors of journals that commission-funded research is published in. “Brexit will be to the detriment of science in [continental] Europe,” he says. “Britain is by far the biggest player in European research. It just has an enormous capacity, and you can’t take out the biggest player without having systemic effects.”

In the short term, he says, the quality of European science will suffer as continental scientists lose the ability to work with their counterparts in the UK so easily. In the longer term, he would expect to see some universities and research teams on the Continent initiating bilateral research projects with UK scientists to compensate for the loss of commission-funded programmes. “But [UK groups] wouldn’t be included in those big multilateral consortia [that exist now],” he adds.

These huge, multi-country projects are where the “excitement” is in European research, according to Jørgensen. Funded to the tune of millions of euros, they give European science a chance to tackle big issues, such as climate change, the future of transport and innovative medicines, he notes. More than one-third of the E80 billion (£73 billion) budget for the current, eighth framework programme, known as Horizon 2020 and running between 2014 and 2020, is spent on this societal challenges “pillar” (the other pillars are “excellent science”, which includes the ERC, and “industrial leadership”).

This type of big-team research is increasingly becoming the norm in science, Jørgensen says, pointing to the considerable rise in co-authored journal papers in recent years. “In some fields, things are getting so complicated that you simply have to do things like that.”

And, crucially, without these projects Europe cannot compete with the US or Asia. “We need to collaborate [across Europe]. We can’t go in 30 different directions and then hope that we are able to keep up with the big innovation powers,” he explains.

Jørgensen thinks that if the UK dropped out of the framework programmes, UK-based researchers who are part of these big teams would probably move to the Continent. “So you might see a slow, steady decline in British research.”

Indeed, some EU nations are already waiting in the wings to snap up those disillusioned with life in a more isolationist UK. Mark Ferguson, the Republic of Ireland’s chief scientific adviser and director general of Science Foundation Ireland, the country’s biggest science funder, says that as well as strengthening bilateral research relations with the UK, Ireland is hoping to attract new talent from across the Irish Sea. “Anyone thinking of leaving the UK [should] come to us,” he says, bluntly.

Jørgensen adds that Germany and France would be happy to accept scientific émigrés. But he warns that any exodus of UK talent to countries with a sub-par research environment could result in their potential being wasted, which would be “everybody’s loss”.

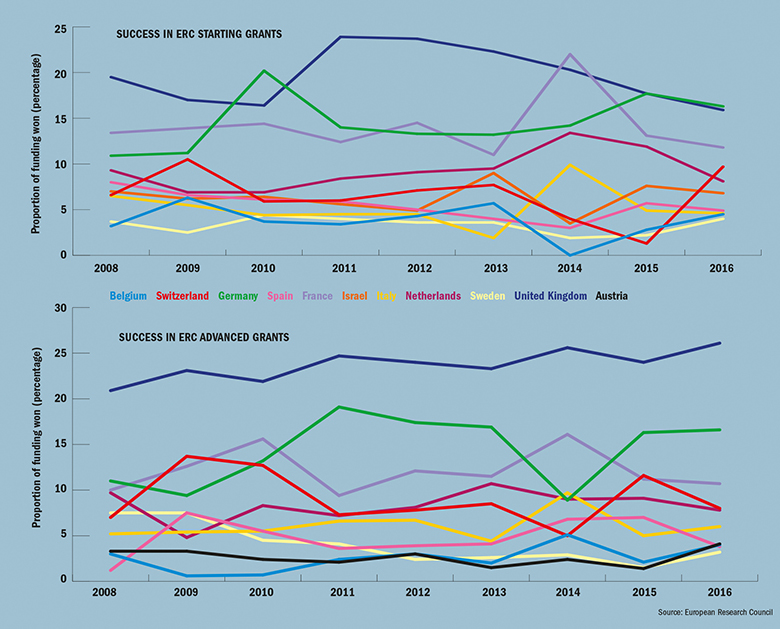

If the UK leaves the framework programmes, it will no longer pay into them, meaning that there would be less money available to fund projects. The commission says that it is not possible to pinpoint the UK’s exact contribution to Horizon 2020 because UK cash goes into the entire EU budget pot. But in 2013, after its rebate, the UK paid more than E14.5 billion into the overall EU budget. That amounts to 12 per cent of the total, but the UK has consistently won a greater proportion of research funding than that. For example, it has been by far the most successful country at securing funding from the ERC. Its lowest proportion of starting grant funding was 15.9 per cent in 2016; for advanced grants, its lowest proportion was 20.9 per cent in 2008 (see graphs above). Most commentators take this to mean that, in terms of research funding, the UK receives more from the EU than it pays in. So, potentially, other countries could see an increase in their research funding when the UK leaves the union.

But Jørgensen says that it is difficult to say which countries would gain in this scenario. The Netherlands is one possibility given its strength in research, but it is not clear, he says, how much spare capacity it has to work on EU projects. Moreover, the allure of the framework programmes primarily revolves around the chance to collaborate internationally. So “losing out on a key partner” would be a major issue, he adds.

The potential Brexit-related funding drop comes at a time when many are calling for a boost to the EU science budget. A recent report by an independent high-level group chaired by former World Trade Organisation director-general Pascal Lamy, known as LAB-FAB-APP: Investing in the European Future We Want, calls for the commission to double the amount that it spends on the next framework programme, known as Framework Programme 9, due to start in 2021. This could be a boon for continental science, particularly if some of this additional funding is channelled into the ERC to fund excellent frontier research.

Kurt Deketelaere is secretary-general of the League of European Research Universities, which represents 23 research-intensive universities throughout Europe, including five in the UK. In his view, the UK’s exit from the EU means that, for the first time, “really difficult decisions” will have to be made over how the EU spends its budget because overall the UK is a net contributor to the EU budget. And this will have ramifications for research.

“We will probably have to see if it is possible to cut [funding to] specific policy fields [in order] to save and to improve [the funding for] other policy fields,” he says, adding that agriculture and the cohesion budget, aimed at poorer EU members, are the areas most often discussed as being suitable for the chop. But there is no guarantee that research will be immune.

“If the UK is not contributing any more and we have to deliver savings in the research and innovation field, then it is clear that continental European universities will lose. Obviously, that would be a very detrimental situation,” he says.

Discussions about how Framework Programme 9 will look are already under way and are likely to be concluded before the UK leaves the EU. But the UK will have no formal influence over the shape of subsequent framework programmes even if it becomes an associated member. In the past, the UK has had a major influence over the drafting of the “rules of the game”, says Deketelaere. So it is not clear how any programme designed without the UK will look in terms of the areas and kinds of research prioritised and how funding will be distributed – both of which could have knock-on effects for the quality of science in Europe.

One country that could keenly feel the loss of the UK from the framework programme negotiations is Sweden. So concerned are the Swedes about the impact of Brexit on the country’s research base that the government commissioned a report, published in May this year by Vinnova, Sweden’s innovation agency, to consider the potential consequences.

The report says that Sweden will lose the support of one of its most like-minded peers when it comes to EU research and development policy. Poorer countries in the south and east of Europe have previously called for the focus on excellence to be relaxed to allow funding to be distributed more equally across the Continent. The UK is one of Europe’s leading advocates for that focus to remain: a stance that also benefits Sweden. If future framework programmes do not align with Sweden’s interests and objectives, there is a chance that the country’s researchers and companies will have less interest in taking part, the report warns.

But, at the same time, Brexit gives Sweden an opportunity to fill the void at the top of European science created by the withdrawal of the UK, acting itself as a beacon of excellence, the report suggests.

For his part, the EUA’s Jørgensen is not convinced that countries with less developed research systems will push for future framework programmes skewed more towards capacity building.

“I know that there is this feeling in Britain that if they leave the table then the [less scientifically able] countries will come and break the programme [but] nobody has been saying that they don’t want excellence as the key to the framework programme,” he says.

“The problem will much more be that Britain leaving will completely upset the balance of net contributors and net benefactors from the EU budget as a whole,” he adds.

Michal Pietras, director of the programme division of the Foundation for Polish Science, confirms that Poland wants the emphasis on excellence to remain.

He adds that Poland already receives a large amount of structural funding dedicated to research from the commission, which is designed to develop infrastructure and strengthen the science base. The country secured less than 1 per cent of funding for both ERC starting and advanced grants in 2016, but Pietras says that the reasons for this are internal to Poland and nothing to do with the UK’s dominance.

If the UK left the EU funding system, Poland would be more concerned about the diminished opportunity to collaborate with its researchers, Pietras says. “If there are previous consortia or well-established projects with cooperation between UK and Polish scientists, they certainly need to be continued and developed. So if there is a problem with this continuity of projects, that would be bad [for Polish science].”

Even more pressing, Pietras says, is the potential loss of the UK as a destination for scientists and students, including those at postgraduate and postdoctoral level, which he says is “vital” to the development of the Polish research workforce. For all the anti-immigration rhetoric voiced during the EU referendum campaign, the warm welcome that Polish scientists and students received in the UK when Poland first joined the EU in 2004 firmly cemented the country as the top higher education destination for Poles. Any stemming of this flow could hit Poland, as the relationships developed during periods of studying and working abroad can influence collaborations later on in scientific careers, Pietras says.

Germany and France are alternative destinations, of course, but language barriers could prove an issue, he adds. “The overall international environment is much greater in Britain than in France [for example]. Being a part of really international groups [is] obvious in Britain, and going there, for most people, feels very international,” he explains.

However, he adds that any movement into Poland of researchers who might otherwise have gone to the UK could prove an opportunity for the country. ERC grant-holders from Greece, Turkey and Portugal may find the country particularly attractive, he adds, explaining that the influx of European structural funds and an ongoing reform of the research and innovation system could prove a draw.

Brexit has thrown up other opportunities for Poland, too. In October 2016, a delegation of representatives from UK universities, including those in the Russell Group, visited Poland to discuss how the two countries could work together after Brexit. Pietras says that the mission, organised by Universities UK International, is the first time that British higher education has really engaged with Poland at this level.

There has also been some talk of UK universities seeking institutional tie-ups or even setting up branch campuses on the Continent in order to retain access to EU funding. These, too, could lend further strength to continental research – although UK universities’ favoured partners and locations are likely to be in central and northwestern Europe.

Aside from funding, the UK has also been hugely influential in other areas of research policy in Europe. Leru’s Deketelaere says that the country has set the agenda in areas such as the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, research integrity and open access. “It is clear that over the past few years, Brussels has had a very good listening ear to London when it came down to the development of research policy,” he says. “If [the UK] is not an EU state any more this level of influence will disappear.”

And while the loss of UK influence over the next framework programme may benefit some on the Continent, the consensus appears to be that there would be many more losers than winners.

Graph: Success in obtaining ERC grants

European research council: ‘if the UK leaves, something will also leave’

The European Research Council is the jewel in the crown of European science. It has funded pioneering curiosity-driven research through a competitive grant system since 2007. During the current seven-year framework programme, Horizon 2020, it has £13.1 billion to distribute.

Unlike the other schemes in the framework programme, which fund groups of researchers or partnerships between academics and industry, ERC grants for the most part go to specific principal investigators.

Decisions about who gets funding are made solely on the basis of excellence and, historically, the UK has done very well. For instance, in 2016, its researchers won 15.9 per cent of the starting grants aimed at junior PIs and 26.1 per cent of the advanced grants aimed at research leaders (see graphs, page 39).

Kalle Heldin, one of the founding members of the ERC and now a professor at Uppsala University, says that the UK’s success has been down to the high level of research in the country. “But it is remarkable that many of those who get ERC grants and work in the UK are not from the UK,” he adds: they come to the UK because of the “excellent opportunities” in science.

“This will now change if the UK is anxious to keep its borders closed…Immigration restrictions are detrimental to the free flow of people that is needed for science to thrive,” explains Heldin, who was vice-president of the ERC from 2011 to 2014.

ERC grantees must spend at least half their time in an EU member state or a country with associated membership, such as Switzerland, Norway or Israel.

Heldin says that it is “difficult” to say whether losing the UK from the ERC would harm the quality of science that it funds overall. “If the UK leaves, of course something will also leave,” he says. But he believes that there is enough remaining excellence to go around.

Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, current president of the ERC, says that researchers in the UK make an important contribution to science in Europe. “What will happen after Brexit is open for the moment. It is difficult to speculate on what the future partnerships between the UK and the EU will be in several areas, including research,” he adds.

Holly Else

后记

Print headline: A hole in the heart of Europe

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?