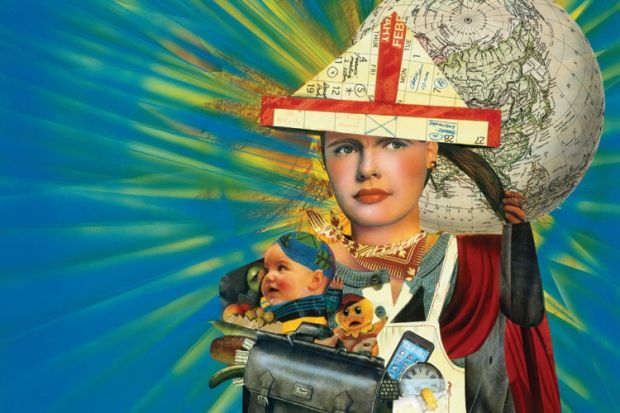

Source: Janet Wooley

In other equally competitive walks of life it is understood that if you have a baby, then you are categorically unavailable for the period in question

Ask an averagely ambitious female academic when she might realistically plan to start a family and the answer will most likely be when she is reasonably advanced into her thirties. The logistical reasons for this are obvious. Once she has jumped through the various career hoops to get herself on a secure footing, the framework for combining a family with an academic lifestyle has never been better: up to a year’s maternity leave, flexible working hours on return to work, and increasing acknowledgement of the need to allow for the impact of childbearing on research trajectories at all levels. But what really happens when a woman decides to go on maternity leave?

I have experienced the difficulties of trying to achieve a “work-life balance” earlier and probably in a wider variety of academic employment contexts than many. Baby number one listened in intently on my doctoral viva while baby number two turned my postdoctoral fellowship into a comparative study of European gynaecological services. My periods of “maternity leave” – the first masking unemployment, and the second equally filled with job searching and grant-application writing as my temporary contract came to an end – were rather less serene affairs than the grand 12 months of family time that were available to my more established peers. So when, finally approaching a sensible age and employment status, I found myself expecting baby number three, I was determined to get some benefit from the legal framework of maternity leave for which successive generations of women have fought. No more editing articles with an infant attached to my breast and a Christmas fairy running around in the background – this was almost certainly my last chance at experiencing early motherhood without the constant interference of early career-hood. Legally, the notion of time off work is clearly expressed, and I was determined to give myself and my growing family priority for the entirety of the allocated period.

However, my baby arrived unexpectedly early: a critical four weeks ahead of schedule. My husband and I both had imminent research submission deadlines, with the initial result that I took some primary literature into the ante-natal ward while he nursed the manuscript of a volume he was editing. Our daughter was born amid discussions of the finer points of English grammar. When we came home from hospital, a pile of unmarked coursework was waiting for me. I knew in my heart of hearts I would have to deal with it, as well as the two unfinished articles, one outstanding peer review, two book reviews, some summer exam scripts, and preliminary work on the special issue of a journal under my editorship, before my maternity leave could start in earnest.

Over the past seven months that have since elapsed, my husband has endured more anguished and inconclusive dissections of my work-life balance than in the previous six years in which we have been juggling the demands of two full-time academic jobs and a family.

Having started out with such high expectations, why have I failed so miserably to fulfil them? What motivated me to keep on working, often late at night or in 30-minute snatches between childminding duties? Officially, the human resources department had waved goodbye and good luck to me for 52 weeks, and altered my salary accordingly.

Initially I blamed my own ambition. But there are, in fact, obvious wider career motivations for making sure a woman remains measurably active while on leave. Women were permitted to submit one fewer output to the 2014 research excellence framework for each episode of maternity leave they had during the census period. However, the time lag between research activity and outputs means that the real fallow period is not in fact in danger of setting in until a year or two after maternity leave – and there are currently no structures in place to allow for this in either research excellence framework submissions or promotions criteria, both of which divide working lives up into arbitrary blocks of achievement. Fellow academics also unwittingly exert pressure: I have lost count of the number of times I have been asked by colleagues up and down the country how my work is coming along since I left it.

Yet in other, equally competitive, walks of life it is understood that if you have left work to have a baby, then you are categorically unavailable for the period in question. One of my sisters-in-law, who works in the financial sector, explained to me that it is utterly unimaginable that she would carry on doing bits and pieces of her job on the side. This is not least because it is a legal requirement for every employee to take a block of two weeks’ leave each year. For reasons of fraud protection, somebody else has to be able to step in and do all aspects of her job. Both company and employees are therefore well schooled in fixed-term replacements. My other sister-in-law, who works in the public sector, does not even have access to her email when on maternity leave.

Among my growing cohort of childbearing academic peers, I have found it is the norm to squeeze in commitments that enhance one’s profile while on maternity leave

But of course the vast majority of academics will baulk at the idea of their being replaceable. Whether going for job interviews or funding bids, we repeatedly have to conceive of ourselves as making an impact on the discipline, the exact nature of which nobody else can match. Our capital is our idiosyncratic accumulation and application of knowledge. The value we place on this provides another explanation for why we find it so hard temporarily to abandon our academic persona. In a reversal of my sister-in-law’s situation, anyone who genuinely replaced 100 per cent of an academic would in all likelihood be committing fraud through plagiarism.

Unfortunately, the flip side of this rather flattering account of academics’ intellectual integrity is that a cash-strapped dean may have good reason to argue that, for immediate operational purposes, a 1.0 lecturer can be covered by a 0.5 teaching fellow – or even an hourly paid graduate, at a pinch. The “academic” side of our contract both is and is not “employed” by the institution. Job lists repeatedly show institutions exploiting this grey area. The result is that early career academics, both male and female, miss out on the valuable work experience that covering the full range of a more senior academic’s maternity leave could, at comparatively low cost, provide. Personnel-strapped departments have to cope with the loss of much more than just a teacher. However the teaching cover is provided, the temporary disappearance of an active researcher and administrator in a small department will also affect workloads and can dampen a collective sense of purpose, as numbers on committees and working groups risk falling below a critical level. And for the academic who is taking time off, the dilemmas caused by her own employment status become all the more apparent. When we need to go on leave, the problems caused by our research are ours for us to solve alone. The successes will, of course, be available to any employer on our return.

The final piece of my motivational puzzle, however, is something much more insidious. Like many academics, I squeeze work in at unsuitable times because, actually, I find it fulfilling. Each time I have sat at my computer over the past seven months, I have thoroughly resented the demands my job continues to make on me. But I have thoroughly enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of carrying out the tasks nevertheless. This has of course led to feelings of extreme guilt, as my older children have asked why they have to go to after-school club when I am on “eternity leave”, and my youngest has been left to grumble in her cot for longer than was fair. I have not had time to go for coffee with other mothers at the school gate, and I have completely failed to be any better at staying in touch with friends and family. My work, by contrast, keeps on demanding and attracting my attention.

It is only very recently, as I have fully acknowledged the conflicting nature of these emotional commitments, that I have come to the following realisation: by deciding to become an academic, I have in fact become something akin to an entrepreneur. This has nothing to do with my particular work ethos. Having asked among my growing cohort of childbearing academic peers, I have found it is the norm to squeeze in commitments that enhance one’s overall profile while officially on maternity leave, such as judging an international translation competition, being treasurer of a national subject association or speaking at a high-profile one-off event. We say yes not least because we don’t know when the opportunity will come round again – and who’s to say it will be any easier to juggle our commitments in a few years’ time? My only mistake was to believe that the legal framework in which my rights as an employee are couched could ever be reconciled with the entrepreneur’s need to manage her affairs on an ongoing basis.

This is surely the nub of the issue. Not only will a research-active academic find it difficult to extricate herself from her career for the full 12 months to which she is legally entitled, in all likelihood she will also not really want to be out of the loop for so long – no more than a small business holder would countenance closing her shop for a year.

Employment law and changing institutional practices have done much in the past few decades to support the careers of women. It has become much more acceptable to request that childcare commitments are factored in to the teaching timetable, or that research seminars are scheduled during the working day. One or two institutions even grant a sabbatical on return from maternity leave. These are very welcome initiatives. However, if my own experience is in any way representative, we need to be much more honest with ourselves about the extent to which this legal framework captures the reality of the entrepreneurial academic’s work-life continuum. Otherwise, we risk ending up feeling all-round failures at one of the most productive and exciting times of our lives.

Entitlements and benefits

- There are few data on periods of maternity leave taken by academics and their return rate. The Higher Education Statistics Agency has begun to collect data on parental leave, however, starting in the 2012-13 academic year.

- The law entitles employees to 52 weeks’ statutory maternity leave. During this time, the employee may be entitled to statutory maternity pay or maternity allowance up to a maximum of 39 weeks, subject to meeting certain qualifying conditions. (Statutory maternity pay is paid if an employee has been in continuous employment with their higher education institution for at least 26 weeks up to the 15th week before their official due date.) In addition most higher education institutions provide contractual maternity pay to their employees, (usually only if they have been employed for a minimum of 26 weeks). A few higher education institutions do not have a qualifying period for contractual maternity pay – for example, the University of Cambridge and University College London – meaning that all employees going on maternity leave are entitled to contractual maternity pay, however long they have worked there.

- When an employee tells their employer that they are pregnant, their employer must conduct a risk assessment and remove risks or make alternative arrangements to protect employee and baby. This has particular implications for academics in science, medicine and veterinary science.

- The employee is entitled to reasonable paid time off to attend antenatal appointments as well as other classes that are advised by a midwife or medical practitioner.

- Employees can take up to 10 Keeping in Touch days during their maternity leave and the nature of work undertaken on these days has to be agreed between employer and employee. These can be used for any work-related activity, including attending training, conferences and team meetings.

- Health and safety regulations prevent employees returning to work for the first two weeks after the birth.

- During maternity leave employers must continue to give contractual benefits.

- A number of universities run schemes to facilitate return from maternity leave. For example, Imperial College London’s Elsie Widdowson Fellowship aims to allow female academics to concentrate fully on their research work upon returning from maternity or adoption leave by reducing their teaching and administrative duties.

Source: Equality Challenge Unit