In a lifetime as a self-appointed “essayist” I have published more than 1,000 articles. There are all kinds of ambiguities about that figure, including revisions and syndications, but it is a good rough indication. Mostly, they were part of continuing series, and the vast majority fell “stillborn from the press”, to use David Hume’s rather chilling phrase. That is, they may have been read and appreciated by somebody, but there was no evidence available to me that this was the case.

But occasionally there was something that put itself in for what might be called the J’Accuse award, meaning that it got a little bit down the track towards Zola’s famous 1898 article on the Dreyfus Affair, which “everybody” in France read.

One of the most prominent of these was an article I wrote on what was then called the research assessment exercise, published in The Daily Telegraph in the spring of 1993. In the usual way, I had no idea when it was going to appear or what its title would be, given that if sub-editors are employed your own title will never be used, however good it is. I actually glimpsed it on the way to the airport. I couldn’t complain about its prominence as it took up a whole page, including a picture of me with my feet on the desk. There was a deliberate paradox embedded in the presentation in so far as the title was “Sorry, I Only Teach”, whereas the pile of books by me on the desk all clearly bore my name (although they weren’t all academic books).

It did occur to me that this might get me noticed, but I barely gave it another thought. I was making one of a series of visits to what is now known as the Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, with the object of turning the department of scientific communism into a politics department (although they called it “political science”). Georgia was in a terrible state: the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development reported a record-breaking 83 per cent fall in its standard of living since its independence from the Soviet Union two years earlier, and law and order had almost completely broken down. Suffice it to say that when you are hiding under a bed listening to the gun battle going on outside and eating the Mars bars you had intended to distribute to colleagues’ children, you don’t give a lot of thought to what people might be saying about an article you wrote for a publication a couple of thousand miles away.

But there was plenty of reaction. Old-fashioned mail was still the order of the day, and when I got back I found close to a hundred items. A substantial minority contained words and phrases such as “reactionary”, “condoning failure” and “cannot be seen to represent the university”, but the majority were along the lines of “courageous”, “honest”, “needed saying” and so on. The bit about representing the university was relevant because I was due to become acting chair of my department. It was clear that some of my colleagues would be disturbed by having a chair who opposed research assessment, so I quickly resigned and had to forgo that particular source of pleasure. Other reactions were more complex, such as those senior officials of the university whose muttered commentaries on the issue began, “Actually, I agree with every word you say, but I couldn’t possibly…”.

I called the RAE a “shyster’s charter” and, nearly a quarter of a century on, I see no reason to change that judgement. The knowledge that your work is going to be publicly ranked is about the most distorting thing one could invent in terms of wasting people’s time. After the RAE, academics spent more time getting work out more quickly than they should have done, and more work was done that was no good to anyone. Less time and effort was spent on teaching and more on networking and arranging to be cited. I remember very early on someone remarking that if you introduce the measurement of performance, people will simply become very good at being measured and that proved accurately prophetic.

After retiring from formal academic life as early as possible, I remember asking a distinguished colleague who was still working how he was spending his time. He quickly told me (having had to make the calculation already for bureaucratic reasons) that he spent some 55 per cent of his time assessing his own and other people’s performance. My real sticking point was the effect this was having on teaching, including the replacement of tried and trusted methods of teaching by “innovatory” replacements that invariably required less effort.

There were originally some potentially valid reasons for research assessment, only one of which turned out to be a genuinely good one. This was indicated in the predecessor concept of the “research selectivity exercise”, which had been introduced in 1986: if there are only the resources for (say) four state-of-the-art medical physics research laboratories, then there should be competition to decide where those four should be and who should lead them. But this doesn’t remotely apply to literary theorists or theologians, or a hundred other disciplines in the humanities. They need resources on only a minuscule scale. I used to enjoy the posthumous fame of Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, pointing out that he produced a far better theory of political power while sitting in jail, in the 1920s and 1930s, with a pencil and a notebook than anyone with a research grant had ever produced.

So how does all this look a generation later? Much has changed including names, concepts and procedures. The key concept of “impact”, introduced in 2014 (when it accounted for 20 per cent of a department’s score), has complemented the monolithic dominance of the idea of pure research quality. The 2016 Stern report – the recommendations of which frame the 2021 iteration of what is now known as the research excellence framework – acknowledges that teaching is important, that academic work can be valuable in many different ways and that not all academic staff should be research-assessed. For a time, when the RAE was introduced in 1992, all of these eminently sensible propositions seemed to be denied or ignored officially.

In addition, it was recently announced that impact will account for 25 per cent of scores in REF 2021, and that each panel will include a particular person charged with ensuring that interdisciplinary research is assessed fairly. Then, of course, there is the recent introduction of the teaching excellence framework, the name of which is a conscious echo of the REF and the intention of which is, at least in part, to act as a counterweight to research’s previous dominance of academic priorities in the UK.

In hypothetical terms of self-interest, I might have been rather pleased by all this. I thought teaching was the most important thing, I had interdisciplinary interests and I wanted to write broadly, as well as academically.

But in terms of the good of universities, I remain, root and branch, an opponent of all forms of unnecessary assessment of academic work. This is not a fundamentalist objection. I don’t believe there is anything immoral about research assessment. My objection is, instead, consequentialist, and starts with what seems to me to be an immediate empirical observation that the official assessment of the value of academic work is bound to do far more harm than good (except, perhaps, if a government department wants to spend £50 million on researching the options for energy policy: in that unusually important case, the best experts should compete for the job).

When I first heard about research assessment I thought it was barmy for the obvious reason that one’s assessment would entirely depend on whether one’s friends or enemies were doing the assessing. I thought of reviews of my own books, the verdicts of which (on the same book) varied from “state of the art” to “complete rubbish”. Research assessment would depend entirely on the panel, wouldn’t it? And if it depended entirely on the panel, then the whole process would be laced with bitterness and corruption, wouldn’t it? There are no underlying agreed criteria for judging intellectual activity and the proper attitude towards people you think are wrong and no use is cheerful and friendly contempt, not mutual respect. All subsequent experiences seem to have confirmed these suspicions. I have often said that the natural sciences would, of course, be different because there could be something like objective standards – only to be told by natural scientists that the problem was just as acute in their fields.

The most fundamental objection to research assessment, however, is the sheer waste of human time and effort involved: all the energies of highly intelligent men and women that go into judging and strategising for a zero-sum game that is quite unnecessary. Then there is all the effort of 200,000 academic staff spent on producing research that, in most cases, is going to be read by almost nobody, and that will have zero impact on a world that would be a better place if they simply concentrated on teaching – or, for that matter, if they looked after their children better or went fishing more often.

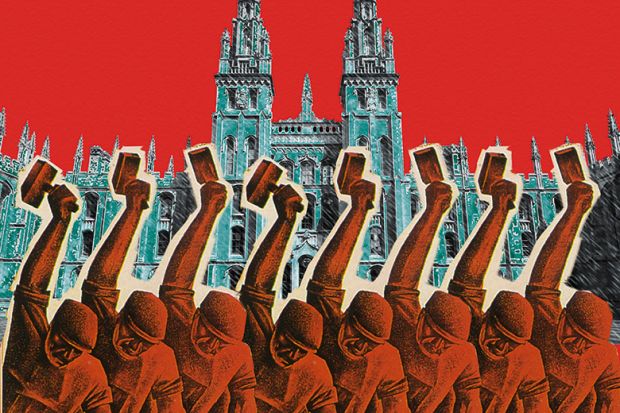

The amounts of money quoted as being distributed by research assessment – the sum is normally put in the low billions – are, frankly, trivial by the standards of this appalling waste of human resources. In effect, the UK decided to imitate the Soviet Union at roughly the time of its demise by establishing a set of production targets for goods that nobody wants. When it comes to ideas, it is only a tiny sliver of the very best that matter and, to quote Hume again, the incentive of “literary fame” is quite enough to motivate such production.

I may have left universities as an employee more than a dozen years ago, but I frequently return and I observe that the modern REF continues to have the same effect as the old RAE: it makes everyone unhappy. Arguably, of course, there may be many things that have made academic staff less happy than they used to be before the early 1990s, but surely the stress arising out of research assessment is one of the most important. Over the years, very good work has come out of calm backwaters, whether those backwaters were monasteries, rural English parishes or relaxed universities. But there is a peculiar contemporary (and often American) equation that sees stress as work and work as stress. It’s as if somebody just didn’t want us to be happy. That more or less tolerable head of department, Dr Jekyll, who used to have the office next door, morphed into Professor Hyde, who defines himself in terms of “management” and “academic leadership”. Now based in a much bigger lair created by knocking together the adjacent offices of three senior lecturers sacked for their lack of “REF-ability”, he devotes himself to “upping the department’s game”, as if he were some sort of fantasy football manager.

If I’m right about what a bad thing research assessment is, then I should attempt an explanation of why governments make such bad decisions. The answer surely lies with public choice theory, which tells us that there is no nice sovereign or legislator making wise decisions that will benefit us over time. There are only self-interested people asking themselves: “What should I be seen to be doing?” And, of course, there are so very many Mr Hydes jumping on the bandwagon.

Lincoln Allison is emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick and the author of books on subjects including sport, political philosophy and travel.

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?