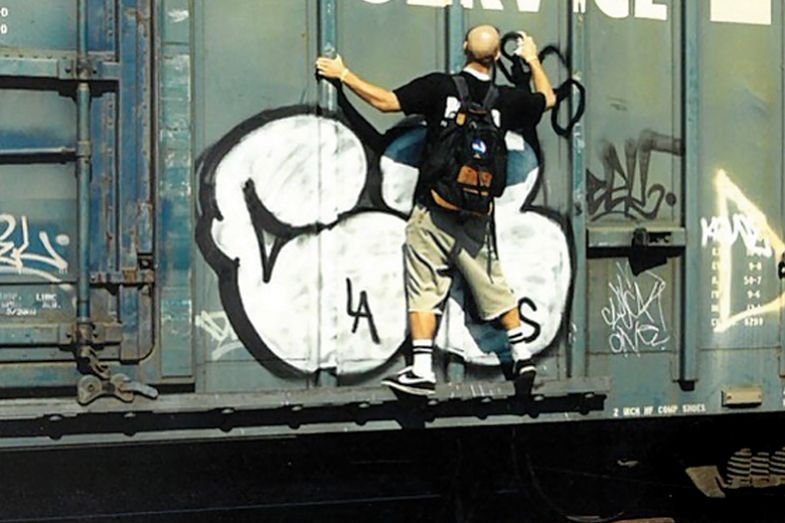

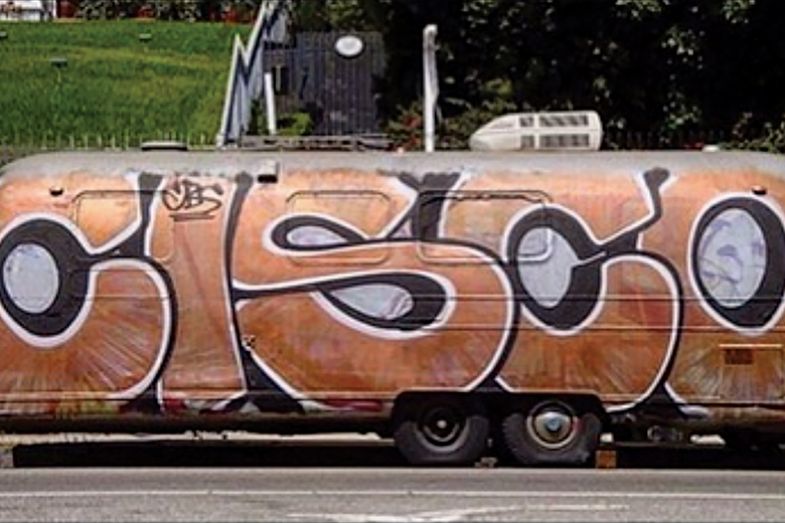

By the age of 16, Stefano Bloch had earned “all city” status. This meant that his distinctive “Cisco” graffiti tag – written in bulging silver and black letters – had been seen from one side of Los Angeles to the other, on light poles and electrical boxes, atop buildings, and on freeway walls and billboards. Achieving that kind of illicit personal fame, however, meant taking huge risks, according to Bloch, now assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Geography, where his teenage exploits as a graffiti writer still guide his research into gangs, law enforcement and the urban environment.

Once, on an all-night “bombing raid” on an overpass near Pacoima airport, Bloch was hit by a speeding car as he ran across the freeway while being chased by a patrol car. “Cisco’s dead, Cisco’s dead,” yelled one of his friends as two others dragged the stricken 15-year-old across six lanes of the deserted road to safety. Neither the police nor the motorist had stopped to help. A few years later, one of his rescuers was shot dead by a gang member less than half a mile away – highlighting another risk faced by graffiti crews who ventured into gang territory in the early 1990s.

The risks to life and liberty Bloch faced in these late-night missions were, however, preferable to what he encountered in his deprived, often horrifying family life, as he explains in his book Going All City: Struggle and Survival in LA’s Graffiti Subculture, recently published by the University of Chicago Press. Hailed as a “vivid autoethnography” and “a shattering account of life in the LA ‘gang hoods’” by Noam Chomsky, no less, it details Bloch’s time as one of LA’s most prolific (and, in some circles, legendary) graffiti writers amid a rootless childhood that saw him moving every four to six months after yet another eviction (and often required him, in the interim, to sleep with his drug-addicted mother in their car).

In this dangerous, chaotic life, violence was never far away. With Bloch’s elder brother running with gangs, a rival gangster would throw rocks through their windows, empty their garbage cans over their yard and, on at least two occasions, shoot at their rented house.

“One of the bullets stayed lodged in the closet door of my bedroom the entire time we lived there,” Bloch notes coolly in Going All City. “One night the local gangster kicked in the door, ransacked the house and nearly beat my brother to death,” he adds, in typically understated prose.

Bloch twice saw his father shot – once at close range by the police while the Nazi-obsessed career criminal, who never spent longer than six months free before returning to prison, was surrendering to them. He also saw lots of gang violence. “Seeing people get punched in the face and kicked in the body is never as terrible as watching someone’s head get stomped into the pavement and hearing their teeth scrape the concrete,” he recalls, of one gang-related attack he witnessed.

The world of graffiti writing provided a kind of partial refuge from all this.

“Graffiti didn’t offer any less violence or risk, but you have a certain control over the violence you might face,” Bloch tells Times Higher Education. “You’re making a conscious decision to take a chance – be it climbing up a building or running from police – but if a gangster jumps out of a car and puts a gun to your head near your house, that’s not a choice.”

Other hazards faced by Bloch’s crew included vigilantes, whose attacks would often be overlooked or condoned by the authorities. A graffiti writer from a rival crew, with whom he had once argued, was shot in the back and killed by one such “hero”. The man was not charged and was later celebrated in the media as a “white knight” for combating graffiti by “Mexican skinheads”, we read.

Such harrowing depictions of the graffiti world and urban violence make for a gripping memoir. But does drawing deep on adolescent memories really count as research – or, in academic parlance, autoethnography? Some intrepid academics may put themselves at the centre of the action, but still usually strive to maintain some critical distance from the events whirling around them.

Bloch is alert to this concern but counters that, because so few scholars emerge from the “marginalised and transgressive subculture” of graffiti, which is “very difficult [for academics] to navigate”, those who do must speak out or their stories would go untold.

“It’s problematic,” he admits. “But I feel my insider status means I am entitled and perhaps obligated to speak about my experiences in a way that benefits my community.” Bloch’s older brother – who gave permission for his story to be told too – thanked him for bearing witness, particularly to the life of their mother, who died of hepatitis C in 2016 after years of drug misuse. “After a book reading, he came up to me, with tears in his eyes, and said: ‘That’s the first time I’ve heard these stories about our mother, and thank goodness someone is finally telling them,’” Bloch says.

Telling the story of inner-city graffitists from his own viewpoint, though, also risks the accusation that Bloch is too partisan. For instance, he dwells only fleetingly on the impact that his or others’ graffiti might have on local communities, noting that Los Angeles spends some $20,000 a day on graffiti removal. Does his autobiographical approach not preclude other equally valid stories?

“I literally cannot see it from that perspective – from those who see themselves as victims of graffiti crime,” he responds. “Until I was an adult, I never had any personal property or knew anyone who owned personal property. If I even tried to address [that point of view], it would be insincere – I would be an outsider.”

Some accounts, Bloch points out, present graffiti writers as gang members, while others see them as “artists or youths with a statement to make”. Yet he has little time for these “useless forms of categorisation” and hopes his insider status gives him a more nuanced perspective on the graffiti community, without either demonising or romanticising it.

As Bloch’s book makes clear, graffiti writers are sometimes gang members or, more often, on the fringes of gangs – part of wider “party groups” of young people. Some, like Bloch, despised the gang “drama” and were instead driven by a mania to spread their tags, but others embraced it. Police invariably did not make a distinction. On one occasion described, “a cop pressed the barrel of his shotgun against the back of [Bloch’s] head as I stood playing [the video game] Street Fighter at the local convenience store” before giving him a “ten-minute lecture on the immorality of gang membership”.

Going All City reveals the meticulous planning behind Bloch’s graffiti raids. His crew would make fake bus passes, travel to faraway hardware stores to steal spray paint and study maps to identify new neighbourhoods. Spraying sessions also required studying different after-dark bus routes right across LA. What some might consider just “chaotic scribbling”, he tells THE, was “practised, purposefully placed and planned well in advance”.

At the same time, Bloch insists that he does not “use the term graffiti ‘artist’ – certainly not about myself”. Although his style has been hailed as iconic by graffitists (an interview with graffiti website Bombing Science last year called him a “West Coast legend”), artistic expression was a low priority for him.

“I wanted to be a skilled practitioner and wanted recognition for my prolificacy, even if I am recognised by the global graffiti community for my letters,” he explains. “My narrative was never about being an artist.”

As such, initiatives that provide spaces for would-be “vandals” to fill with art are unlikely to do much to reduce tagging and would certainly not appeal to graffiti writers such as Bloch, since they fail to understand something fundamental.

“Graffiti is now mainstream and an accepted aesthetic, but however much you commodify or contain it, you can never get away from what gives it its force – illegal transgression,” contends Bloch. “Someone putting on a jacket and backpack and hitting the streets to write [their] name on a piece of public infrastructure will always be raw, real and transgressive.”

Bloch can justifiably claim to give outsiders many important insights into the world of graffiti writers. But that still leaves the question of why he adopted the format of a memoir, rather than a more typical academic mode of writing. Academic theory and social commentary are present in the book, Bloch insists, although “between the lines”. Moreover, far from being easier to write as a memoir, Bloch found it “a much more difficult writing process as it’s far easier to hide behind academic jargon”. But he wanted to create a space for readers to draw their own conclusions about the events unfolding on the page: “It’s more interesting for me if readers are filling the gaps rather than an academic doing it for them, but that editing process required a lot of pulling back.”

Recounting distressing childhood memories, notably of his mother, was also very emotional, particularly when recalling old childhood homes and hangouts. “I would sometimes find myself crying so hard that my stomach hurt at the end of a day of writing,” he says.

That admission is surprising given the restrained prose style that characterises Going All City. Episodes that could run on for much longer – the time when Bloch was chased by a gun-toting drug addict, an eviction in which his family lose everything or his habit of washing his clothes with soap in the shower as a teen – are brief and matter of fact. One evening, parked up on a dark street, Bloch witnessed a man being beaten to death and thrown in a dumpster. Without saying anything, his mother turned on the engine and drove on. “When things like that happen, it’s frightening at the time but moving on is a necessity,” reflects Bloch on why he doesn’t dwell too much on any one episode. “Since then, I’ve lived in much more privileged spaces and seen that people don’t seem to be able to move on from far, far less traumatic events in the same way,” he adds.

Strangely enough, it was graffiti that originally led Bloch to higher education. On his bombing raids across LA after he was kicked out of school aged 17, he made a point of crossing university campuses because he was attracted by their calm environments. Enrolling as a mature student at a community college, he later transferred to the University of California, Santa Cruz, before doing a PhD at the University of Minnesota.

Now at Arizona, Bloch’s work explores areas of urban life beyond graffiti, such as the effect of anti-gang legislation on minority communities and how public attitudes to the police are shaped by the fact that they are increasingly likely to come across them while out driving rather than in their local neighbourhood.

“I may not be researching or writing about graffiti, but it is often the lens I use to study vulnerable communities,” he claims. “I still see the city as a graffiti writer does.”

后记

Print headline: Urban legend