How can we live well in the universities of the future? This was the question we aimed to address in our workshop at last year’s International Conference of the European Utopian Studies Society, in Newcastle. The conference had attracted academics from disciplines across the social sciences and humanities, and we were looking forward to a lively discussion about a subject close to scholars’ hearts. But no one had turned up.

My co-host and I looked at the clock and then at each other. We asked ourselves what we should make of all the empty chairs. Will universities of the future be empty, lonely and silent? Will future academics feel more like Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe than the happy residents of Thomas More’s political paradise?

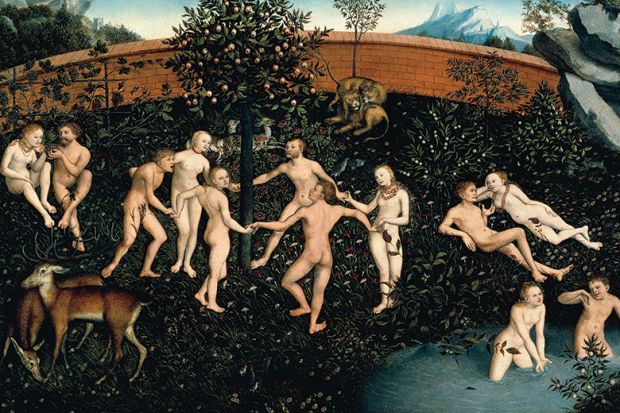

This year, Utopian thinking is back in academic fashion thanks to the 500th anniversary of More’s original satire, whose Grecian title literally means “non-place” or, alternatively, “good place”. We could argue that universities are in desperate need of Utopian escapism. The pages of Times Higher Education are a frequent reminder of the dark side of contemporary university life and its burdens of government meddling, managerialism, bureaucracy and consumerism. Like the colonised island in Gilbert and Sullivan’s 1893 opera Utopia, Limited, the university is becoming a corrupted, capitalist artefact.

But, good Utopian that I am, I believe there is still hope. You may be even less inclined to agree with me when I reveal that I am writing from the perspective of a university business school. However, I would argue there is no better place on campus to gain glimpses of possible realities, because business schools have already become “the future” that academics from other disciplines so desperately fear. Here, the money-making imperative of the university-for-itself often overrides other ideas and values.

In addition to the workshop at the Utopian Studies conference, I also presented a satirical paper about life in university business schools, called “factories for the mind”. This session was much better attended than the one on universities of the future, and I drew on insights from authors of technocratic dystopias – Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Yevgeny Zamyatin – to think through the implications of organising education around particular institutional logics.

The factory is perhaps the most disturbing image of education: it is a “non-place” of learning. The factory for the mind is managerialist but devoid of leadership. It operates on principles of efficiency and standardisation rather than quality. It measures everything but does not use evidence for making decisions, owing to the invalidity and unreliability of its measurements. Its products – minds – are pulled and squeezed and shaped through myriad contradictory procedures, and are then required to rate their own value based on the journey through the production line.

But if the factory for the mind is the future, why am I hopeful? The answer is that during the year since that deserted workshop, I have experienced what it is like for a non-place to find glimpses of becoming a good place. This has involved looking out across the university, reaching beyond boundaries and forming new relationships and friendships in unlikely places.

At my own institution, the University of Southampton, I have been working with a growing group of staff who want to find ways of reinventing the business school. There are a number of different approaches to this. Some writers take a polemical position, such as Martin Parker in his 2002 book Against Management: Organization in the Age of Managerialism. The Carnegie Foundation’s 2011 book Rethinking Undergraduate Business Education: Liberal Learning for the Profession is more pragmatic in finding links between business and humanistic spaces for learning. My own Utopian approach is not an attempt to ignore our contemporary reality, but to discover new possibilities that are at the same time critical of the deep structures of social institutions.

By reaching out, I have found it possible to make connections across many different academic disciplines. More importantly, I have found it helpful to work in ways that are less disciplined. In our undergraduate business programmes, we have been working with students and staff from many departments, including humanities – in particular philosophy and history – and also engineering and applied technology. We meet together regularly in what we call the co-design group – “co-” here simply meaning a coming-together across boundaries – to discuss all aspects of the course and the way learning is actually taking place. This is nothing like the unfruitful ceremony of so many “staff-student liaison committees”, but a lively and imaginative space. Anything, from deciding what to put on the syllabus to discussing the process of assessment, is discussed at length, and the group’s decisions feed directly into the classroom within days.

This way of working has led to glimpses of new forms of higher education, in which narrow disciplinary paradigms and tribal identities are rejected and students and staff share a love of inquiry, rather than seeing their interaction as a service encounter. My own views about the nature of disciplinary boundaries have been reshaped through rewarding conversations with a philosophy PhD student who has worked with us as a class tutor. I have discovered that it is possible to have more in common with an academic from a department apparently poles apart from your own than with disciplinary colleagues.

The search for Utopia also involves celebrating the possibilities that technology offers for overcoming disciplinary boundaries. Owing to its cross-disciplinary appeal, students from web and internet science have joined the business programmes co-design group and enrolled on our modules.

They have also been challenging the traditional pedagogical approach of learning through lectures. In particular, they have co-created a new digital learning environment. To give a sense of how this works, think of the application interface on any smartphone or tablet. Apps such as Pinterest, Twitter and Storify can be used to store information in text, image and video, and share it in open, non-linear ways. An element of the curriculum may start as a reading or seminar room discussion but, through the co-creation process, quickly becomes a series of unfolding conversations on web platforms that augment face-to-face interaction. Every student can personalise this environment by simply deciding which apps to install and which platforms to participate in. There is no expectation for the course staff to control or oversee all interactions, because the content has been created by students through their own learning and exists only to serve that personal process.

This openness of learning and knowledge means that there is no longer such a divide between what students do at university and what they perceive to be the “real world”. Our students are finding links between what they are working on for course assessments and other social and economic aspects of their lives, such as contributing to causes they care about. Our student-edited business blog is a testament to this approach. Students from the co-design group have used their experiences to find paid work opportunities, participate in political debate and contribute to scholarship about higher education by attending academic conferences and writing papers on the topic. These are just some early examples of what is possible by working in new and fundamentally different ways.

In his recent book, The Hidden Pleasures of Life: A New Way of Remembering the Past and Imagining the Future, Theodore Zeldin, the conversationalist philosopher, notes how over millennia human civilisations have clashed through two contrasting visions of social life. On the one hand, there is the view of civilisation as a city-fortress, surrounded by walls, protecting itself against barbarians and rejecting the vices of the external world. On the other hand, there is the city-port, always hungry for what it does not possess, searching for a better life by trading with strangers and importing novelties without too many worries about where they might lead. Many university disciplines have become more like the former than the latter. Threats of government policy, markets and commercialisation have led to their becoming increasingly defensive and closed in.

If we go back to More’s island imagery, we can think of universities today as drifting archipelagos of academic disciplines. Each island has a cathedral at its centre, extolling the discipline’s canons and creeds. The occupation of every islander is to serve the unending process of building and embellishing the cathedral. And the limited size of most islands gives their inhabitants a continual and inescapable reminder of their vulnerability to the dangers posed by foreign lands.

The institution of the business school grew over the 20th century to become a perverse kind of island: a large landmass with a huge population, but, instead of a cathedral, only a sandcastle that keeps being stepped on. For this reason, business schools have nothing to lose in opening their gates to foreign influence. But they are not alone in needing to find ways of reimagining higher education. Many, if not all, disciplines and departments face the threat of insular, inbred decline.

In 1953, the president of the University of Chicago, Robert Hutchins, gave a series of lectures on the University of Utopia, asking what universities should ideally become. Hutchins was a traditionalist in the Western canon, believing that universities should build a compulsory core curriculum that all students should master as the foundation, before specialising in a profession or occupation. But Hutchins also believed that the University of Utopia would be a connected and coherent intellectual community, not a dispersed archipelago. “In Utopia,” he wrote, “the object is to make it possible, and even necessary, for everybody to communicate with everybody else. Therefore, the University of Utopia is arranged so as to force, in a polite way, the association of representatives of all fields of learning with one another.”

I am not Utopian enough to think that contemporary university departments will ever coalesce around a core curriculum shared by all students. But I do believe that “disciplinarity” has reached its limit and should be looked on as a 20th-century idea. Disciplinary theories and methods have become too insular to address important questions in the contemporary world.

This is recognised, from a research perspective, by Amanda Goodall and Andrew Oswald, who have argued in Times Higher Education that the social sciences need a “shake-up” through more interdisciplinary working. But I would go further and argue that a “post-disciplinary” stance is more helpful, as it opens up the possibility for questions and ways of working that do not belong to any current discipline at all.

I am not suggesting that we close down disciplinary departments. Instead, we should create new spaces – uninhabited islands – that can be occupied by post-disciplinary thinkers who want to think about the world in more open-minded ways. Although my colleague and I were like Robinson Crusoe and Man Friday – abandoned and lonely – at our Utopia workshop, Crusoe’s author might also have recognised our deserted island as the possible site for establishing a post-disciplinary Utopia. After all, Defoe embodied the Enlightenment “pre-disciplinary” intellectual life, living as inventor, businessman, novelist, politician and secret agent. He also saw gentle commerce as a way to overcome vulnerability and suffering in human life. In a year to celebrate Utopian thinking, we should remember Oscar Wilde’s words: “A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.” It is time to discover Utopia in our universities.

Mark Gatenby is associate professor in organisations at the University of Southampton.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A better place

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login