We can’t blur the key messages, and we have only 50 words per label – 50 words that an 11-year-old can understand

Translating bits of an academic journal article into language an 11-year-old can understand is every bit as hard as it sounds, but it is all part of the job for museum label writers.

Long gone are the days when a paragraph of curator-speak was hung on the gallery wall for visitors to understand as best they could. Today’s museums depend for much of their funding on appealing to everyone who walks through the door, from toddlers to specialists, and the labels must play their part.

I have been working as a text consultant for new galleries at the University of Reading’s Museum of English Rural Life, which will open in October thanks to funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Wellcome Trust. Curators, academics, archive and education staff are all involved. Themes and narratives have been chosen, such as “town and country” and “a year on the farm”. Topics covered include badger culling, 19th-century child mortality in rural areas, artisan cheesemaking and the Glastonbury Festival.

Half a dozen sources may be used for one label. Research often starts with the acquisition file for each object. This may hold little more than the donor’s name and the date the object entered the museum, but, with luck, it may also contain letters, magazine articles or catalogue pages.

Journal articles and books are then consulted. When were mantraps outlawed? (1827.) What was the price of the “hermaphrodite” wagon from Lincolnshire, which could be converted into a cart? (£20.) Is farming still one of the most dangerous occupations? (Yes.) Familiar research problems arise – too much or too little information; the challenge of creating a narrative out of disparate or conflicting sources. We write our own labels and review each other’s.

Vocabulary is simplified, abstractions are made concrete and passives become active. Label testing carried out with 11-year-olds by audience development manager Phillippa Heath showed that some do not understand words such as “livestock” and “agriculture”, but we can’t omit them. The line “organophosphates were found to cause neurological side-effects in people” becomes “some of the chemicals used were toxic”. Coopering is explained. Subtleties have to be sacrificed.

The labels have their own version of peer review, and comments arrive back from science, agriculture and history academics. Sheep dipping is in the “autumn” section of a gallery, but, we are told, it was also carried out in summer. Oh dear. We can’t blur the key messages, and we have only 50 words per label anyway. Certain wavelengths of light are sometimes used to reduce aggression in chickens, instead of debeaking them, we learn. No room. Can we include alternative names for the disease brucellosis (undulant, Crimean or Malta fever)? Mmm…we’ll try.

The knotty problem of value judgements comes up. Should labels suggest that wagons are beautiful or that signs can be ugly? Surprisingly contentious, but assistant curator Ollie Douglas champions detached objectivity. So words such as “beauty” are probably for the chop. And then on to formatting: TB or tuberculosis? Ampersands for company names? Dashes or hyphens?

At their best, the labels are accurate, concentrated and use objects to help the visitor understand people and societies. My current favourite explains that a sedge mattress from Hampshire “was made to support a mother during childbirth or a corpse after death. After use it would have been burned. Life in rural communities began and ended in the home.”

Once this stage is over, the labels are tested on the gallery walls with the graphic designers. Other questions arise. Do they lead people to the objects or distract from them? Are there too many? Will visitors still learn something even if they browse only a few?

University museums are places where the academy and wider society meet, and, at their best, labels reflect this. And, for the people involved, a tweet by project officer Adam Koszary sums up the feeling best: “Satisfying specialist interest vs boring other audiences [is] fun to grapple with”.

Rebecca Reynolds is a freelance museum education consultant.

We picked up one polar bear cub and took it on board a snowmobile. We then had to chase after the mother and her other cub, and release the one we had captured

For the past six years, I have had a most unusual job: explorer-in-residence at Plymouth University.

Alongside work as a mountain safety consultant for the seismic industry, I have carried out a number of expeditions with the support and sponsorship of the university. I skied from Canada to the Geographic North Pole in 2010, collecting ice samples for marine research along the way. And I skied solo to the Geographic South Pole in 2014, responding to questions from schoolchildren along the way via a web platform.

I have also found ways to build exploration more directly into the key academic tasks of teaching, research and preparing students for employment. For instance, I took about 250 undergraduates on to Dartmoor for two days as part of science communication leadership programmes. More unusually, I led much smaller groups to the Canadian Arctic. One group climbed the highest peak in the Queen Elizabeth Islands so that we could send the Queen a loyal greeting for her diamond jubilee in 2012.

There have also been two expeditions to Baffin Island. We visit the Qikiqtarjuaq Inuit community of about 500 people on Bear Island and then set off by boat to the Auyuittuq National Park. We walk the length of the park, which takes about 12 days, mapping the glaciers as we go. I have been tracking glacial retreat on Baffin Island for about eight years, so environmental science students get a chance to contribute to a research project closely related to their coursework.

One of the most dramatic moments occurred in 2012 when we were on snowmobiles with some Inuit hunters and were about to be dropped off. As we turned a corner, we came across a mother polar bear and two cubs. They were frightened by the noise and, to our great distress, rushed off in different directions. We pursued one of the cubs, picked it up – very carefully – by the scruff of the neck, took it on board a snowmobile and covered it with a tarpaulin to calm it down. We then had to chase after the mother and her other cub, and release the one we had captured. Fortunately, they soon started barking at each other and were joyfully reunited. Later that day, we were equally delighted to discover three parallel polar bear tracks leading down to the sea.

Such expeditions are both expensive and physically demanding, since we each have to carry rucksacks weighing more than 20kg. But they also provide students with a wide range of personal and career development skills. I help to mentor them through the process of obtaining grants from sources such as the Royal Geographical Society, the Scientific Exploration Society, the Roland Levinsky Memorial Fund (created in honour of a former Plymouth vice-chancellor) and Santander Universities. Students go on to learn how to work as a team, overcome physical challenges, communicate with the Inuit and track changes in the Arctic environment. A number have been inspired to go on to PhDs in polar science.

Antony Jinman was explorer-in-residence with Plymouth University between 2010 and 2016 and is chief executive of Education Through Expeditions.

I spend most of my time making apparatus for use in research labs and teaching. But then there is the more weird and wonderful stuff, like triple pigs and breasts

As a university glassblower, I’ve had a fair few requests that have made my wine glass slip shatteringly from my fingers – metaphorically, at least. I was once asked to supply a human breast and lips for an artist’s exhibition. I had never worked on anything like this before, but when the artist came to collect it she was so impressed that she commissioned me on the spot to make another breast with a removable nipple, which formed part of a show called Carnally Consumed.

I started glassblowing when I was just 16, working at a small family-run business in Birmingham producing apparatus for large scientific suppliers. I spent the next 10 years learning the basics, gradually progressing to more complex pieces. Days, weeks and even months were spent performing the same routines: cutting glass tubes to length, simple flame-polishing of the ends and then rounding them off to form a test tube.

I became a member of the British Society of Scientific Glassblowers, won a number of their competitions and eventually came across the University of Birmingham’s vacancy for a scientific glassblower in the society’s journal in 1993.

I spend most of my time making pieces of glassware for use in research labs and teaching. I regularly produce the exact scientific equipment required for particular experiments, from simple glass test tubes to more complex items such as triple-walled reaction vessels and multi-valve vacuum lines. Glass breaks easily, so the huge advantage of having a glassblower on site is that I can usually repair anything that gets broken on the same day, which minimises any disruption to the experiments.

But then there is the more weird and wonderful stuff. One sideline is bespoke gifts, most recently a glass decanter in the shape of the university’s Aston Webb building for a former pro vice-chancellor. I was once asked to create a glass replica of the human digestive system. This proved too time-consuming to undertake, but I can usually make something like the triple pig – a tiny pig inside a bigger pig inside an even larger pig – in about 45 minutes. (These were inspired by the traditional ships in glass bottles, but I wanted to do something a little different.) These pigs – I can do hedgehogs, too – form nice gifts for people visiting the glassblowing studio.

Students in the university’s School of Arts and Jewellery sometimes ask me to make things for them (and occasionally come back once they’ve graduated and moved on to personal projects, as in the breast example). A current project is a full-length glass corset for a student based at Aston University, which is going to be worn on the catwalk sometime next summer.

Even more exciting was the gift I made for former universities minister Lord Willetts when he visited the campus. Since he was often known as “two brains”, I created a human head complete with eyes, nose, mouth and ears – and two glass brains inside. I’m told that it still sits on his mantelpiece.

Stephen Williams is the glassblowing workshop manager in the University of Birmingham’s School of Chemistry.

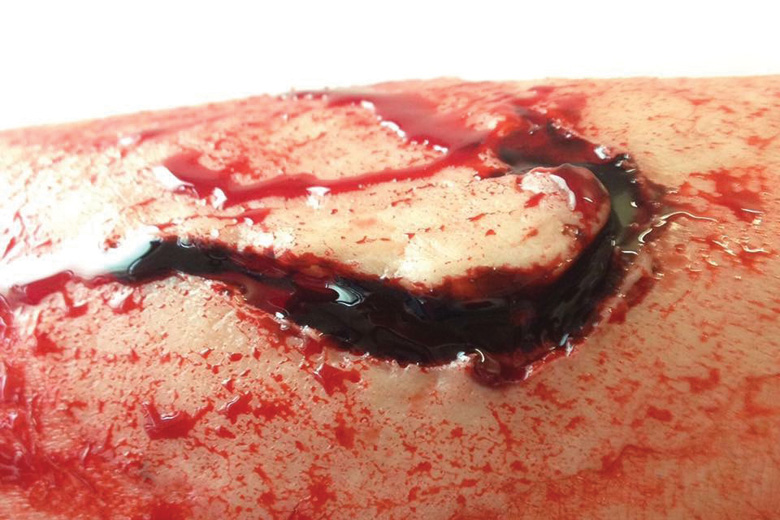

I apply wounds, scars and burns to volunteers. I’m always delighted if a student gasps when they see a wound that looks and smells infected

My light-bulb moment came when a lecturer told students to imagine a wound on a volunteer’s arm. I had joined Bucks New University in 2011 as a laboratory technician responsible for setting out equipment in the skills sessions that help student nurses put the theory they’ve learned into practice. There had to be a more effective form of learning experience than just asking them to use their imaginations.

I researched the available training, submitted a business case and secured funding from the university to complete a casualty make-up course. I use my moulage skills to apply wounds, scars and burns to volunteers. I’m always delighted if a student gasps when they see a wound that looks and smells infected and asks if it’s real. It’s much better for them to have that reaction with a volunteer than to risk offending actual patients. I’m not aware of any other institution that employs someone to perform exactly this role.

My skills have developed to meet increasing demands for authentic clinical simulations. I work closely with academic colleagues to design scenarios that ensure that our students understand as fully as possible some of the difficult things that they may encounter during placements and once they qualify.

The university has state-of-the-art skills labs equipped to resemble a hospital ward and operating theatre, and the manikin patients can be programmed to interact just like real people. To increase the authenticity, I create body fluids such as blood, vomit, sputum and urine for use in these simulations. I have developed the recipes for these through trial and error. The artificial sputum, for example, is made from whipped egg white mixed with combinations of French mustard, over-fried onions and food colouring. The urine is made of varying strengths of coffee, salt, sugar, nail polish remover and lemon juice so as to yield a range of test results. But there are always new challenges. For instance, I was recently asked to recreate the soiled nappies of newborn and breast-fed babies for our child-nursing students.

Colleagues have nominated me for a number of awards, and the prize money from one of them part-funded my attendance of a course run by the British Association of Skin Camouflage.

When I’m not at Bucks, I work as a camouflage practitioner to empower people with skin conditions. I have also been enhancing my skills through a master’s in medical and healthcare simulation at the University of Hertfordshire, which should help me to improve my lesson plans and debrief students more effectively. This should ultimately feed through into increased patient safety.

Sam McCormack is skills and simulation area supervisor in the Faculty of Society and Health at Bucks New University.

When I unwrapped the packages, I discovered a mummy’s hair and a bottle of holy water from Bethlehem. A mummified finger rolled out across the desk

As a mature student at Swansea University in the 1990s, I watched the Egypt Centre being built, and I became its first volunteer. I am now its assistant curator. This makes me – alongside curator Carolyn Graves-Brown – responsible for many unusual objects, such as a magic wand, a demon-shaped bell and a Book of the Dead (a set of spells intended to help a recently deceased person pass through the underworld to the afterlife).

Yet it is looking after the mummies that presents the most complex and amusing challenges. We have carried mummified remains in boxes around campus, to and from the 3D scanning lab in the department of engineering; a mummified dog unfortunately proved too big for the turntable and had to be put back in storage. We have driven ancient coffins to the conservation department in a white van, hoping that we weren’t going to break down or get stopped by the police. We have taken a mummified snake and a mummified crocodile to the local vet for an X-ray to check what was to be found under the bandages. And we have taken what was thought to be a fake mummified baby to a CT scanner in the College of Medicine only to discover that it was, in fact, a tiny fetus of 12 to 16 weeks’ gestation; the ancient Egyptians wanted a baby lost through miscarriage to have the chance of an afterlife, so they surrounded it in layers of linen and put it in a painted coffin shaped like a baby.

Then there was the time we loaned a Graeco-Roman mummy mask to an exhibition at the Prado gallery in Madrid. They put it in a beautiful air-sealed case while it was on display and then packed it up for me to take back in a padded metal case. I had to keep it with me at all times, so we had to buy a separate plane ticket and seat for it. It was given the window seat and had to be securely belted in.

I have also had memorable experiences dealing with institutions wanting to loan things to us. On one occasion, John Taylor, an assistant keeper at the British Museum, brought us a bag of objects that the Rev John Foulkes-Jones, a 19th-century collector, had amassed while in Egypt. When I unwrapped the packages – still in newspaper dating back to the beginning of the 20th century – I discovered a mummy’s hair and a bottle of holy water from Bethlehem. A mummified finger rolled out across the desk, stopping right next to my uneaten apple.

Since most of our mummified human remains are kept in storage, it is part of my job to deal with enquiries from researchers and the general public who want to see them. Some people have strange ideas about mummies, so the requests can be pretty startling. One enquirer wanted to “free the spirit” of the deceased. Instead of just telling me what they wanted to see, therefore, I was asked to wait in the storeroom and concentrate until I received some sort of message from the beyond.

Wendy Goodridge is assistant curator at the Egypt Centre, Swansea University.

后记

Print headline: You do what...?