On 24 November 2016, the great and the good of Colombian higher education made their way through Bogotá’s noise, congestion and pollution, past the graffiti murals of exotic birds, serpents and mythological scenes, to a plush reception hosted by the US embassy.

The occasion was a Thanksgiving lunch. But the Colombians could surely have been forgiven if they had preferred to give thanks not so much for the American harvest as for the dividend that they hope to reap from the revised peace deal that their government had signed that very day with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc): the Marxist guerrilla organisation infamous for its more than half century of involvement in kidnappings, extortion and the drugs trade.

The deal – whose original version had been rejected by Colombian voters in a referendum the previous month – was ratified by the country’s parliament within a week. And the higher education sector is poised to carry out the research and establish the access programmes that will help clarify issues of social justice and reintegrate the ex-combatants: tasks likely to be crucial in building long-term peace.

But as well as fulfilling this national agenda, many leaders of higher education institutions are hoping that the more stable post-conflict environment will also enable them to become more effective players within global higher education. Indeed, the reason that the US ambassador was able to gather so many of them together for stuffed turkey and pumpkin pie was that they were already in Bogotá – once reputed to be among the most dangerous big cities in the world – to attend the eighth Latin America and the Caribbean Higher Education Conference, which was devoted to the theme of internationalisation.

Still, the dining room would have had to be the size of a university refectory to accommodate the close to 300 leaders of the country’s complicated tertiary education system. The system includes 82 universities, as well as assorted “university institutions” (that award only undergraduate degrees), technological institutions and professional technical institutions. Claudia Aponte González, a consultant who works with Colombia’s ministry of national education, told the conference that the ministry is committed to promoting internationalisation, but had struggled to come up with a one-size-fits-all model. There were institutions located in border cities; institutions committed to “Bolivarian” pan-Andean ideals; institutions that offered only online courses; institutions focused on regional development; institutions in special territories such as small Caribbean islands; even institutions in places where the climate was so bad that the ministry had never managed to send someone to carry out an assessment. Each had different ideas about what internationalisation should mean for them.

Major attempts at reform in the sector have proceeded in parallel with the long peace negotiations. President Juan Manuel Santos’ National Development Plan for 2014-18, Todos por un nuevo país (All for a New Country), established education, alongside peace and equity, as one of its three “pillars”. Santos – the winner of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize – has also announced an ambitious aspiration for Colombia to be the best educated country in Latin America by 2025. Perhaps the most obvious practical consequence of this has been a laborious, ongoing process – carried on with partners such as the British Council – to streamline the country’s system of qualifications, improve the status of technical education and create new pathways into universities.

For international higher education consultant Liz Reisberg, many of the challenges facing the equatorial nation apply across much of Latin America.

“All countries are responding to the challenges of massification, which started 20 to 30 years ago,” she says. “Higher education went from being an elite enterprise to trying to incorporate anywhere between 30 and 60 per cent of the age cohort. [It is currently in the region of 50 per cent in Colombia.] The traditional universities just couldn’t accommodate that…Most of the ministries backed off on the restrictions on setting up universities and allowed very rapid growth with very little quality control.”

As the dust has settled, Reisberg goes on, most countries established systems of quality control. That includes Colombia, and the nation is also notable for “a pretty well-established private sector”, whose elite tier has a level of research productivity on a par with that of the public universities, she says.

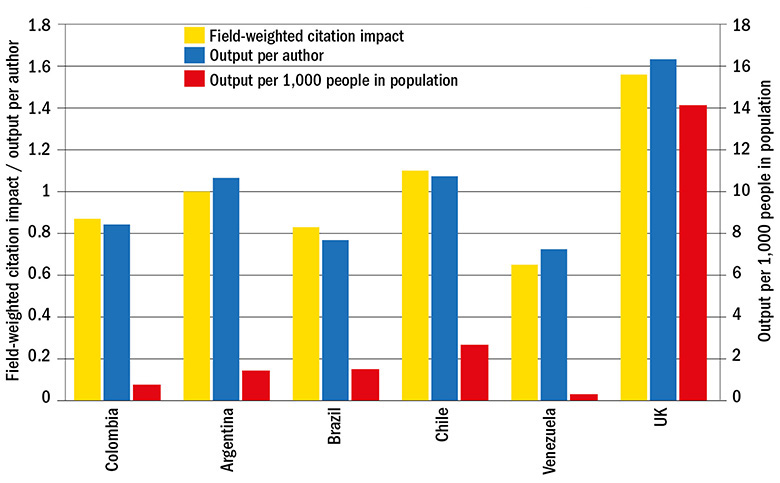

Indeed, there seems to be general agreement about the strength of the top Colombian universities. Four institutions – the University of the Andes, the University of Antioquia, the Universidad del Norte and the Pontifical Bolivarian University (UPB), Medellín – feature among the top 50 in Times Higher Education ’s Latin America University Rankings for 2016. That is more than any other country except Chile (11 places) and the regional giants Brazil (23 places) and Mexico (eight). Citation data provided by Elsevier (see graphs opposite and on page 37 and charts on pages 36 and 39) also suggest that Colombia is quickly increasing its research output, whose quality bears comparison with the strongest performers in the region, especially in physics and astronomy.

Colombia was identified last year by Times Higher Education as one of seven nations with the potential to become significant players in global higher education ( “The new breed on the charge”, Features, 24 November). This was on account of its respectable research quality, its increasing research output and its high and growing student enrolment rate.

A report called Education in Colombia, published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development last April, also praises many aspects of Colombian higher education. However, it is highly critical of the country’s “outdated, inequitable, and inefficient” system for distributing public resources. Established in 1992, this system allocates 48 per cent of the entire budget for public universities to just three of the 32 institutions, and leaves 20 out of 39 public technical colleges without “regular” subsidies. Given that total student numbers have more than quadrupled since 1992, the system’s “rigidity, lack of definition and scope” make it a major obstacle to progress, the report says.

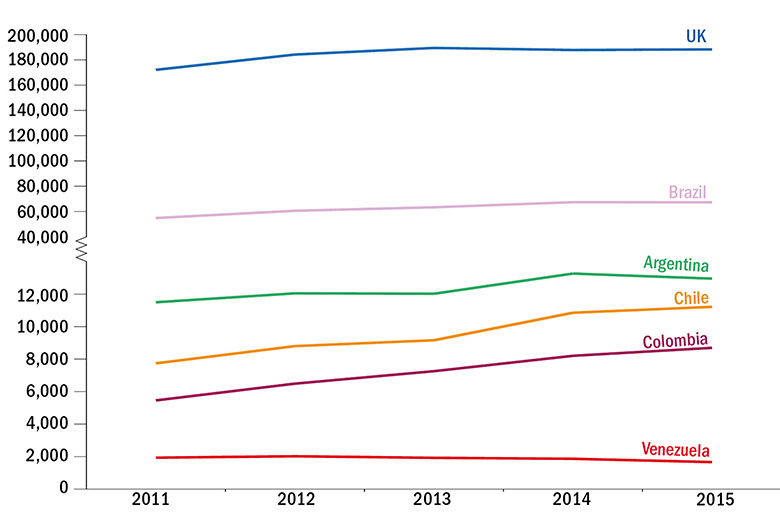

Growth in output of papers

Source: Elsevier's SciVal tool

Colombia’s long decades of civil unrest are, of course, another important background factor to take into account when assessing its higher education. In a PhD thesis titled “Conflict, postconflict, and the functions of the university: lessons from Colombia and other armed conflicts”, awarded by Boston College in 2013, education consultant Ivan Pacheco describes how the conflict was “part of the day-to-day life” of many public universities. “Struggles for the political and economic control of campuses have been bloody and claimed several victims,” he writes. In one case, about 50 academics and students were kidnapped by guerrillas; elsewhere they were “killed, tortured and disappeared”.

Precisely because of the “almost unquestioned prevalence of the left-wing ideology on campuses”, Pacheco explains, the extreme Right also “decided to take over some public universities, particularly in the north of the country”. Meanwhile, universities’ very autonomy could make them “more attractive to outlaw groups…Corrupt politicians have attempted (and sometimes been able) to gain administrative and political control of these institutions”.

Anyone who visits Bogotá’s “White City” will take Pacheco’s point about “left-wing ideology”. This is the main campus of the National University of Colombia, close to the centre of the capital. Surrounded by a fence, it covers an area of 600 acres, complete with observatory, stadium, children’s playground, pop-up cafe, restaurant and white faculty buildings. At its heart, where little stalls sell food, is the Francisco de Paula Santander Plaza, more often known as “the Che Plaza” on account of the huge painting of Che Guevara on a facade opposite the library.

The leftism of student activists was also apparent in their opposition to plans to reform the sector – including the system for distributing funding – embarked on a year after President Santos took office in 2010. According to the OECD report, the protesters objected to only “one highly controversial clause – to allow for-profit tertiary education institutions”, but the volume of their opposition “caused the whole…reform proposal to fail”.

There seem to be no current plans to revive the reforms.

A rather different figure from Che Guevara greets visitors to the Bogotá campus of Uniminuto, perhaps the only university in the world named after a television programme. This was established by the Roman Catholic priest Rafael García Herreros, famous throughout Colombia during his lifetime because of his daily one-minute “God slot”. When a vacant lot was donated to him, he created a whole district on the outskirts of the city, complete with houses, textile workshops and even a museum of contemporary art, which looks like a miniature version of the snail-shaped Guggenheim Museum in New York. It was also here that he established a university “inspired by the Gospel and the church’s social mission” to provide “quality education within reach of everyone”. It now has branches in 85 cities and teaches 120,000 students. Distance learning, online courses and evening classes help it to reach out to the underprivileged, indigenous communities in remote cities and other groups largely ignored by the rest of the sector. Scholarships helped to support almost 90,000 students in 2015 alone.

This points to another key educational challenge Colombia faces: social exclusion. In the words of J. Salvador Peralta, associate professor of political science at the University of West Georgia, the central question in Latin American higher education is: “Who do we leave behind?” Like several other countries, Colombia has “much more demand for higher education than [it] can possibly supply efficiently and at a high quality”. This has led to “very difficult questions about where to allocate resources to get the most return for [its] money”.

The government’s flagship policy for widening access, known as Ser Pilo Paga (Hard Work Pays Off), has given 10,000 scholarships a year since 2014 to pupils from poorer backgrounds who achieve excellent results in the national school-leaving exams. A new student loan scheme was also introduced in 2015.

Pablo Navas Sanz de Santamaría, rector of the University of the Andes – the top Colombian institution in the THE Latin America University Rankings 2016 – calls Ser Pilo Paga a “very, very significant” initiative that had “an immediate impact in making universities much more inclusive and diverse”. His university has also secured philanthropic funding for other programmes targeting similar underprivileged groups. As a result, says Navas, “42 per cent of those selected last semester” to study at the university now come from such backgrounds.

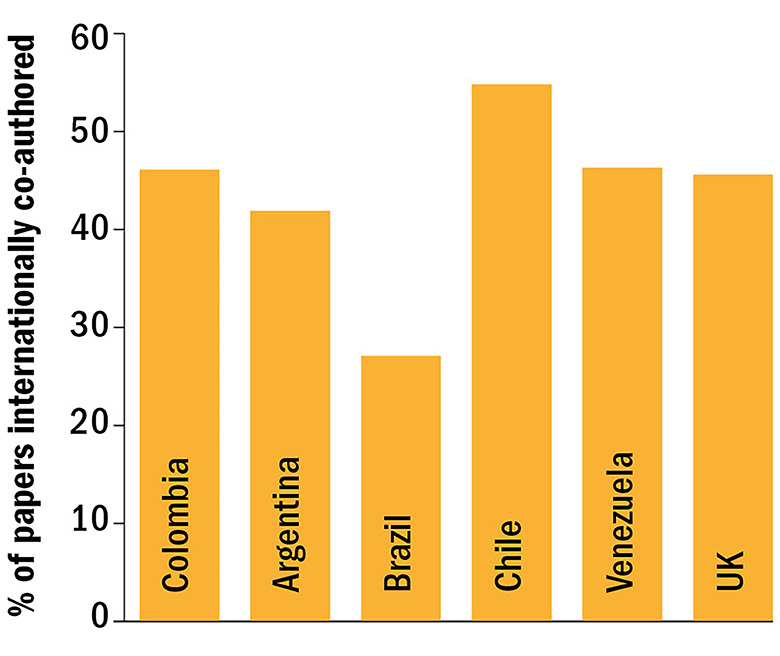

Internationalisation is not an entirely novel concept in Colombia. According to Elsevier, the proportion of the country’s papers that were internationally co-authored between 2011 and 2015 is high: 46 per cent. This is virtually identical to that of the UK, and several universities represented at the Bogotá conference have actively embraced an international mission.

“Internationalisation is absolutely crucial for us,” Marta Losada, president of the city’s Antonio Narino University, tells THE . “We put in a strategy 10 years ago to sign up faculty without PhDs to go abroad [to do a doctorate] and [we] see lots of international collaboration as a result.” The university is now following this up with “a strategy to hire people with doctoral degrees from all over the world”. Losada is actively pursuing partnerships in the Spanish-speaking world but is also keen to “implement more programmes in other languages, particularly English, over the next 10 years”.

Alberto Roa is vice president for academic affairs at the Universidad del Norte, a private university set up in 1966 in the Caribbean region. His institution is also committed to a comprehensive approach to internationalisation, which “seeks not only to increase the inbound and outbound mobility of students and faculty, but also to work on internationalisation at home, in order to have a global environment on the campus”. International conferences, events and courses in English are among the measures adopted to “strengthen global citizenship skills in our students”.

International collaboration

External partners confirm the effectiveness of such strategies. David Wilson, professor of human developmental genetics at the University of Southampton, attended the recruitment fair accompanying the higher education conference, looking for Colombian postgraduate students in areas well beyond his own specialist field. This is because “the ability and experience of graduates from high-ranking Colombian universities is comparable to those who study in the UK”, he says. “Their level of English language is usually very high, and the students are enthusiastic and have an excellent work ethic.” A further advantage is that Colciencias, the Colombian research council, “recognises the importance of postgraduate scientists gaining training outside Colombia and offers competitive PhD scholarships”.

Mike Proctor, vice president for international affairs at the University of Arizona, is similarly enthusiastic. His university is seriously engaged with about half a dozen Colombian universities and he claims that Colombia’s research universities “are fabulous universities and on a par with anybody”. Many of Arizona’s Colombian contacts are “world-class global scholars, presenting multilingually at conferences and publishing in Nature ”, he adds.

Yet it is safe to say that this excellence represents the tip of the iceberg. Apart from the funding system, which does nothing to incentivise efficiency, the OECD report also laments the comparatively low academic abilities of typical Colombian school-leavers; the high dropout rates from universities; the low proportions of undergraduates going on to postgraduate study; and the “lack of employer engagement in the governance and delivery of [tertiary education]”. Ministry figures indicate that, as of 2012, there were only seven people per million in Colombia holding doctoral degrees, compared with 31 in Chile, 42 in Mexico and 69 in Brazil. The Latin American average is 37.

Quality assurance also remains somewhat cumbersome. At the most basic level, all institutions and programmes are required to meet minimal standards in order to be certified. Universities can also apply for Voluntary High Quality Accreditation but, given that it has little public recognition, many have not felt it worth the effort to go through the laborious process. In mid-2015, a further instrument known as the Modelo de Indicatores del Desempeño de la Educación (Model Performance Indicators for Education) was introduced. According to critics, this imposition from on high lacks transparency and amounts to a ranking of Colombian universities based on criteria that implicitly penalise those, such as Uniminuto, that are doing important work but are not operating on standard models.

A new version of the indicators, therefore, involves far greater consultation with universities and a wider range of assessment criteria. According to a ministry spokesman, the results will be used neither for making funding decisions nor as “a punitive measure” but rather to show which universities are “more developed” and which “need to be improved”.

According to consultant Reisberg, Colombia is also “ahead of the game in collecting really good data”. This includes areas such as research, labour market returns for particular qualifications and “value added” (as measured by tests of those entering and completing university courses). However, as the ministry spokesman admits, this energetic information-gathering has proved somewhat fruitless, since “families do not use the data to decide on a university” and “universities do not use the data to measure how they are doing in comparison with others”, preferring to rely on international rankings.

A further range of recent programmes have attempted to make Colombia more globally competitive in higher education. Colombia Cientifica (Scientific Colombia), which launched in October 2016 with funding from the World Bank, is a joint project between the education ministry, the research council Colciencias and the Institute for Student Loans and Study Abroad, known as Icetex.

It consists of two separate schemes. One, “Passport to Science”, provides funds for at least 90 students to do full master’s degrees, and 100 more to do PhDs, at leading foreign universities, largely in areas such as health, water supply, environmental issues and agriculture, which are required by the labour market and are linked to the peace process.

The other scheme, “Scientific Ecosystem”, supports partnerships between major foreign universities, leading Colombian research universities, regional universities and industry. Arizona’s Proctor describes it as “a fabulous strategy for building capacity nationally”.

Also new are international summer schools. Begun last summer, these last about a month and bring together about 300 Colombian academics and students with international experts, including Nobel prizewinners, to address one of the three key “pillars” – equity, education and peace – flagged up in the president’s National Development Plan.

The goal, according to a government spokeswoman, is to “teach Colombians about best practice, to make students more international in their outlook and to connect students and professors with international experts”. The courses also serve a broader goal of enabling the academic community to “take part in the construction of our politics, help build a strong political centre and get involved in the resolution of our problems”.

A further scheme was launched by the ministry in 2015 in collaboration with “Colombia Challenge Your Knowledge”, a network of nine universities devoted to “promoting Colombia abroad as an attractive destination for international students and professors”. This provides coaching by consultants to universities’ internationalisation offices. A series of “methodological guides” to internationalisation are also being drawn up.

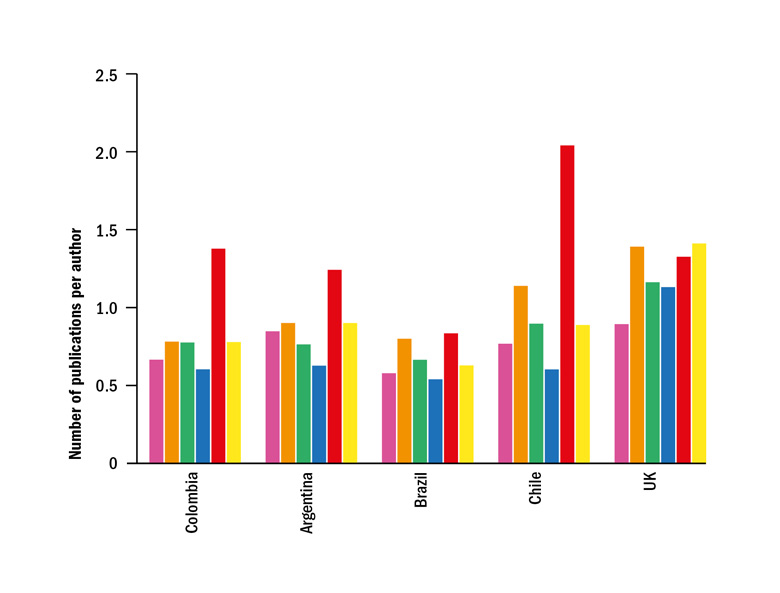

Productivity by subject

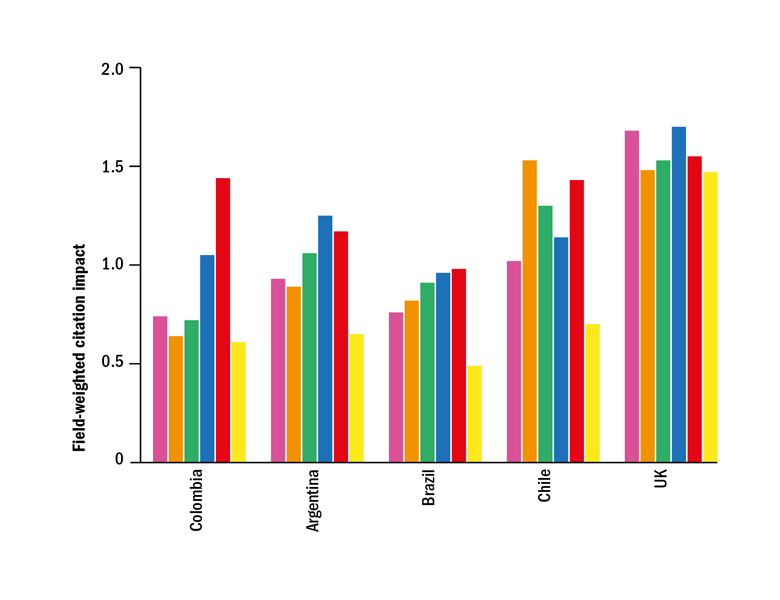

Quality by subject

Note: All data courtesy of Elsevier’s SciVal tool. All data refer to the years 2011-2015

Despite all this, the ministry spokeswoman is frank about how far the country still has to go: “As of now, few academics can write in English,” she explains. “That is one of the biggest challenges we are working on. We are really encouraging bilingualism, but since universities are autonomous, the ministry cannot force them to do things.”

Delegates at the Bogotá conference also pointed to major challenges, even while acknowledging that important (if sometimes cumbersome) structures had been put in place.

Luis Alejandro Arévalo Rodríguez is head of internationalisation at Bogotá’s private EAN University. Although his institution manages to do “a fair amount of applied research, working closely with enterprises in areas such as clean energy, entrepreneurship and sustainability”, he points to sector-wide difficulties in giving research the priority it deserves. “When you hire professors at a PhD level, they expect to [be able to conduct] research, so if your university is not committed to [this], it is difficult for them to be happy,” he says. But “very few” universities can afford to allow staff to concentrate exclusively on research, and most ask them to focus on teaching.

Sonia Marcela Durán Martínez, vice-president for international affairs at Del Rosario University, agrees that “the country does not have enough funding for science, so it’s a huge challenge for private universities”. When Colciencias was set up in 1968, it was “clear that it had to fund laboratories and research as well as mobility, but this remained at the level of good intentions because it was never given [enough] funds”.

The coming of peace is naturally welcomed, but universities seem cautious in their optimism about what it is likely to mean for them. Universidad del Norte’s Roa expects “great economic investments for the post-conflict transition” but sees no evidence that increased funds will be directed towards higher education. If they aren’t, it will mean “no resources available to finance very costly investments, such as facilities, technology, laboratories and libraries”.

Rector Navas at the University of the Andes is extremely keen for the Ser Pilo Paga initiative to continue after its initial four years. He would also like to see more “top-notch researchers” addressing issues such as “drug trafficking, biodiversity, the new justice structure to be implanted”. Unfortunately, he believes that a system directing 10 per cent of oil and mining royalties towards science, technology and innovation was “incorrectly designed and hasn’t worked out well”, since responsibility for distributing such funds is in the hands of “the governors of the different states”. With elections approaching, he fears that both the extension of Ser Pilo Paga and any plans to reform research funding may fall foul of short-term political pressures.

It seems that only time will tell whether 24 November becomes permanently established in Colombian university calendars as a day for thanksgiving.

Overall quality

Source: Elsevier's SciVal tool

后记

Print headline: Peace. Hope. Progress?