This Halloween, we should perhaps spare a thought for the Devil.

Milton’s hero and Marlowe’s “regent of perpetual night” is now a shrunken figure. While belief in God, or some kind of benevolent cosmic force, remains stubbornly high, fear of a personal Satan is increasingly confined to minorities of devout Catholics and evangelicals. In the words of the historian Euan Cameron, belief in the Devil has drifted “into the area of metaphor and symbol”.

This does not mean that the ancient enemy has vanished. Indeed, the popularity of TV dramas such as Midwinter of the Spirit, and the spooky carnival of Halloween, suggests the continued allure of the demonic. But the recasting of the Devil as a figure in popular entertainment tacitly acknowledges his reduced status. It is as a fictional monster, rather than a real threat in the world, that the Devil today attracts most attention.

In many ways, we should be grateful. Belief in a personal Devil and the agonies of Hell stoked religious conflicts in the Middle Ages and the Reformation, and contributed to the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries. As many as 50,000 people may have died in these persecutions; and in England, which largely escaped the horrors of continental witch panics, at least a hundred were executed in the eastern counties in 1645-47.

These events show the sometimes appalling consequences of “thinking with demons”. But the Christian tradition of engagement with the Devil is considerably richer than the grim history of witch persecutions might suggest. Indeed, the historical theology of Satan contains at least two useful insights for our own time.

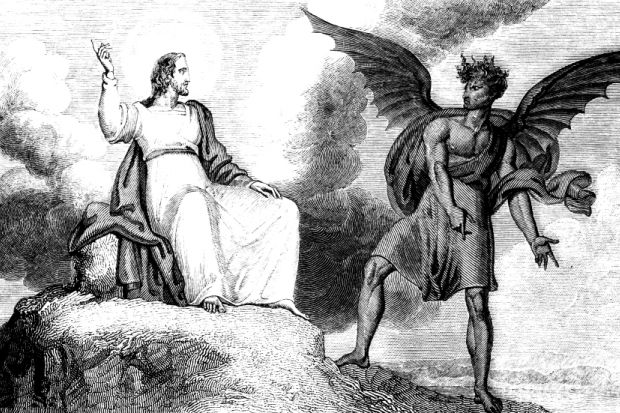

The first of these is the deceptive nature of evil. The Christian tradition has emphasised the Devil’s desire to appeal to the best as well to as the worst parts of human nature: to appear, as St Paul wrote, “as an angel of light”. As Pope Gregory the Great warned in the 6th century, the powers of darkness are “lying in wait for good people in secret”, and “deceive them under an appearance of holiness”.

It was in this capacity, rather than in crude appeals to greed or lust, that the enemy proved most lethal. After all, it is relatively easy to detect the stirrings of immoral desire, but harder to resist the lure of apparently benevolent ideas. And how many leaders have gained a following by promising destruction and pain?

The awareness of Satan’s subtle methods brought an end to the witch trials at Salem, Massachusetts in 1692. The minister Increase Mather denounced the persecutions as an injustice inspired by the Devil. It was the enemy’s ploy, Mather argued, to cause well-meaning Christians to execute innocent people under the deluded belief that they were destroying evil. This view prevailed and the trials ceased.

Without understanding that people can do dreadful things for seemingly good reasons, it is easy to imagine that destructive behaviour is the preserve of evil outsiders. Today the depiction of terrorists often reflects this tendency, which some psychologists call the “myth of pure evil”.

The second lesson from Christian demonology is the power of bad environments. When pre-modern thinkers contemplated the fallen world, they recognised the myriad false beliefs and corrupted institutions that helped to sustain Satan’s dominion. In the Protestant tradition especially, it was believed that men and women could not act well in such a world without divine grace.

Relatively few today would accept this bleak assessment; and atheists would challenge the claim that only supernatural assistance can elevate human conduct. But there is much to be said for the view that individuals are swayed in their moral behaviour by external contexts. The psychologists Stanley Milgram and Philip Zimbardo have shown that ordinary people are capable of shocking violence against innocent strangers under the right (or wrong) conditions. The history of the 20th century provides ample support for this conclusion.

None of this would have surprised a demonologist such as Mather. He belonged to a world that accepted implicitly the sway of external powers on human behaviour, and expected these influences often to produce evil. In contrast, many modern Westerners presume, perhaps naively, that they are free agents with sufficient moral strength to “do the right thing” in most circumstances.

The Western culture in which Satan was a real and terrible presence, accepted by almost all thinking people, is now so remote that an effort of imagination is required to reconstruct it. Few will regret its loss.

But that world understood two things that are easily forgotten: that great wrongs are often committed with good intentions, and that vigilance is needed against the “principalities and powers” that can lead ordinary people into darkness.

Darren Oldridge is senior lecturer in history at the University of Worcester and author of The Devil: A Very Short Introduction.