Dr. Otakar Fojt | UK Science & Innovation Network

Partnerships in Central and Eastern Europe are becoming increasingly attractive options for foreign scientists and research institutions. Research is thriving across much of the EU13 with the Czech Republic leading this trend, and Poland, Hungary, Estonia and others following closely.

Up to now, these countries have often been overlooked as potential research partners by leading science nations. Moderate innovators, they do not fit into the obvious moulds. They are not science superpowers, and nor are they developing nations, eligible for overseas development aid. They are something else entirely, possessing their own unique qualities and advantages. The UK, Germany and others are now recognising this.

Potential for future partnerships

“Opportunities here are incredible,” says Professor Andrew Miller from King’s College London, going on to recommend that researchers seeking partners should look around Central and Eastern Europe. Prof. Miller knows what he’s talking about. In January 2017, he and his team were awarded a Czech research grant of about £7 million to develop needle-free patches for human vaccination that only need to be placed under the tongue. This research is done at the Veterinary Research Institute in Brno, a city with over 80,000 HE students, and a high number of research centres. The Central European Institute of Technology employs over 900 researchers while industrial research leader Honeywell Technology Solutions has more than 1800 research engineers on its staff.

Such concentrations of research excellence and expertise can also be found in other Czech cities. Olomouc hosts the second oldest university in the Czech Republic with 22,000 students. Four newly established research centres at Palacký University in Olomouc specialize and excel in room temperature organic magnets derived from sp3 functionalized graphene and other advanced materials; high-throughput drug and biomarker discovery; plant structural and functional genomics contributing to wheat genome analysis, and a centre of sport sciences. The Czech capital Prague is home to the renowned Charles University, 39 Institutes of the Academy of Sciences and many other public and private universities.

When the iron curtain fell in 1989, newly gained freedom and opportunity across Eastern Europe gave rise to a tremendous wave of euphoria. In the former Czechoslovakia ‘dissident’ Václav Havel became ‘President’ Vaclav Havel and the whole society and economy began to transform, quickly catching up with more advanced western neighbours. Now, 28 years on, we see a very different Central Europe where a generation have grown up with the birth-rights of democracy and freedom to travel. They speak foreign languages, take smart phones and internet for granted, and use social media as a natural means of communication.

Significant investments in Research infrastructure

The transformation has been massively supported by western European countries. Leading professors based in Warsaw, Prague, Budapest or Sofia won scholarships offered by western governments, science foundations and charities. Similar support went to science infrastructure. As Central European countries joined the EU, they took full advantage of EU science programmes, using structural and cohesion funds to improve national research infrastructures. In 2007–2013, in addition to national science budgets, Poland invested € 9.3 billion into the national research infrastructure, Czech Republic € 4 billion, and Hungary € 2.5 billion. In 2015, these countries achieved the highest annual science spends in their overall national histories, reaching science spend as 1.95 % of GDP in the Czech Republic, 1.36 % of GDP in Hungary and just over 1 % of GDP in Poland. Altogether, these three countries have some 220.000 experts working in science and engineering according to EU statistics and about 350.000 research articles in SCOPUS database in 2011–2015.

Bibliometrics have not yet captured the results of this rapid investment in science infrastructure and transformative quality growth. However, those engaged in research on the ground here in central and Eastern Europe right now are amazed by the available technology, skills and enthusiasm. Increasingly often, this translates into research partnerships.

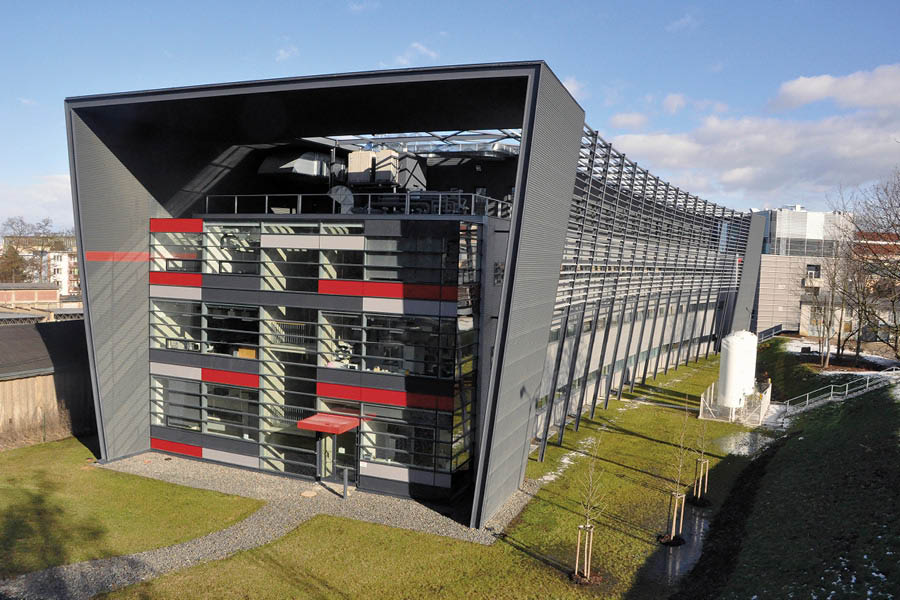

The Extreme Light Infrastructure (ELI) project, nicknamed ‘CERN for lasers’ is one such exciting example. ELI is based in three locations of Central Europe (in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania) with an overall budget of € 920 million paid from EU structural funds and national resources. It is the largest science project in new EU member states, aiming to build a new generation of the latest laser equipment, 10 times more intense than the best currently available.

Not all is perfect, of course. Research management, science ivory towers, clans of self-supporting academics, brain drain and the new research evaluation methodologies are frequently-discussed issues here as in many other parts of the world. They are however a secondary story to the major improvement of research quality, combined with state of the art equipment and opportunities to build partnerships with the best in the world.

In line with Professor Miller’s opinion, I believe that Central and Eastern Europe is a research region that the curious should certainly explore.