By using holographic technology in ambitious conceptual projects, the composer Eugene Birman is creating a bold new multimedia aesthetic for classical performance, and telling the stories most important to modern society

The hologram made its cultural debut in 1970s science fiction, most notably on the big screen in Star Wars, but it was not until 2012, at the Californian music festival Coachella, that it became a practical proposition for live performance. At Coachella, the late rapper Tupac Shakur’s image was rendered onstage for a technologically assisted duet with Snoop Dogg.

It was a pop-cultural moment that resonated, and its impact was not lost on Eugene Birman, associate professor in the Academy of Music at Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU). A renowned composer, Birman would deploy holographs in classical music to express the themes in his work and challenge the traditional presentation of the art form.

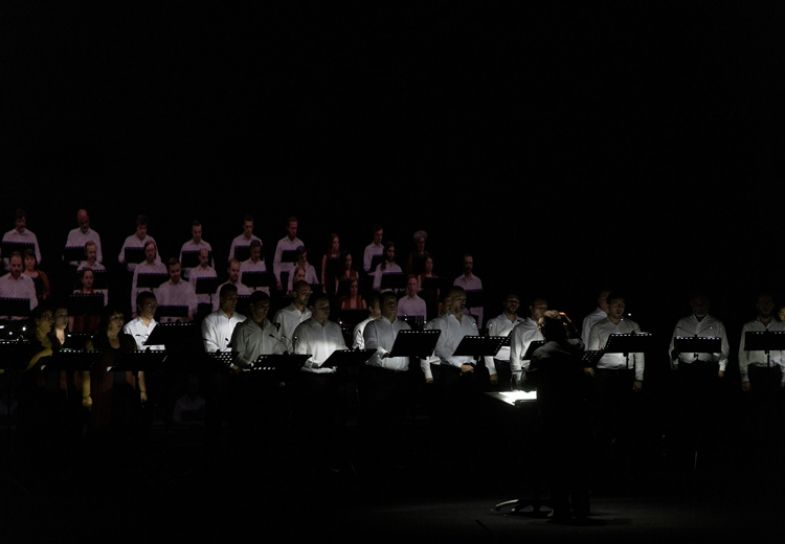

Birman composed and presented a tech-cantata with Giorgio Biancorosso, professor of music at the University of Hong Kong, titled Os Dias Mais Longos e os Mais Curtos, or The Longest Days and the Shortest Days. The work was also presented with Angolan-Portuguese writer Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida and written for the Gulbenkian Choir. Holographic tech was used to present a hyperrealistic facsimile of a choir before a live audience at the Gulbenkian Auditorium in Lisbon. The work interrogated how society engaged with art – particularly in a post-pandemic landscape, where screens mediated the relationship between artist and audience.

“A lot of orchestras and bands went onstage and performed for an empty hall, and that was screened to your computer,” Birman says. “For the musicians, it is a completely different experience to perform for an empty hall. You have none of the energy.” The Longest Days swapped perspectives; this time the audience were in a concert setting reacting to simulacra.

“We would project a performance onto the stage that wasn’t really happening, and that served as a research question – really an artistic prompt that had its basis in, ‘how much do we value culture and are we willing to lose it forever if we keep going this way?’” explains Birman.

Realism was the goal. The audience needed to be sold on the image. Once realism was established, 17 minutes in, the image was manipulated, revealing the conceit. “What was interesting was at the moment when the image was pulverised the audience clapped,” Birman says. “It seemed like, for once, technology became art. It gave the audience 17 minutes of faith in something that didn’t really exist, and for me that was really satisfying.”

Having augmented classical performance and stage production with holographic technology in The Longest Days and in Aria 空氣頌, the latter delivered as part of a multidisciplinary project from HKBU researchers that dramatised the effects of air pollution, Birman is now seeking new ways for the hologram to enhance stage productions. He sees HKBU’s support for this work as an example of higher education supporting research that has an immediate impact on society, perhaps ushering in a new era of modernism in classical music.

“We have to look for new tools rather than grinding out the ones we already know,” Birman says. “A lot of institutional education in classical music, specifically, is about using those tools instead of discovering new ones, so for me that is the question of modernity and innovation.”

Find out more about the Academy of Music at Hong Kong Baptist University.