Most of the rising share of first-class degrees in the UK over the past decade is “unexplained” by factors such as improvements in student entry standards, and the tripling of English tuition fees in 2012 may be a reason instead, a key report on grade inflation has concluded.

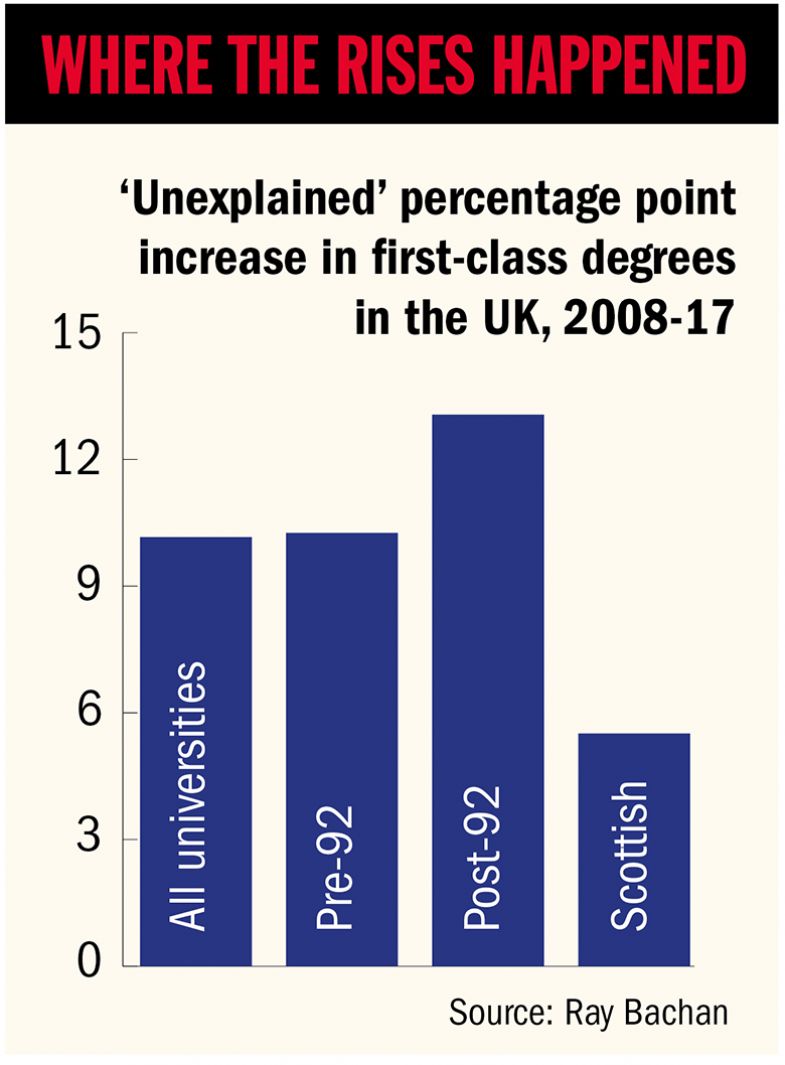

According to the report, commissioned by Universities UK and written by an academic expert on grading trends, about 10 percentage points of the rise in firsts from 2008 to 2017 cannot be explained by changes like students starting universities with better grades or universities becoming more “efficient” at teaching.

With almost 24 per cent of all bachelor’s-level degrees resulting in a first last year, this means that more than 40 per cent of those degrees were “unexplained” by such factors, meaning that they could be the result of pure grade inflation – in which higher marks are awarded for work no better than submissions that would have received a lower score in the past.

This “unexplained” element in the share of firsts being awarded started to appear from the 2010-11 academic year and has been growing ever since, says the study by Ray Bachan, senior lecturer in economics at Brighton Business School.

It is larger at modern universities, according to the analysis, with 13 percentage points of the rise in firsts at post-92 institutions being unexplained, representing about half of all the first-class degrees awarded by such institutions last year. Meanwhile, Scottish universities – which do not charge tuition fees to students from Scotland or other European Union countries – have the lowest share of unexplained firsts with around a third in this category in 2016-17.

Dr Bachan’s findings feed into a wider report on grade inflation by UUK, GuildHE and the Quality Assurance Agency, which claims that “much of the upward trend in grades seen across the sector will have been legitimately influenced by enhancements in teaching and learning”. But it also admits the influence of other factors that could be “described as inflation”.

The organisations have launched a sector-wide consultation based on recommendations in the report, which include reviewing the structure of degree classifications, asking universities to publish algorithms used to determine final marks and looking at the influence of league tables on degree awards.

Dr Bachan’s analysis looked at both the rise in “upper” or “good” degrees – firsts and 2:1s – and firsts alone. However, it concludes that “overall, these results suggest that a large part of the rise in the proportion of upper degrees could be due to grade inflation in the first-class category”.

It adds that “it would appear that the sector may need to review its marking and grading processes to ensure [that universities] can continue to protect the value of qualifications and that we can be confident in the academic standards that underpin them”.

Dr Bachan tested his model by looking at additional factors, such as the gender and socio-economic background of students, but did not find anything strong enough to change the trend seen in the main analysis.

He says that there could be reasons for the unexplained rises that are not down to pure grade inflation, such as better student motivation, improved marking procedures or the treatment of borderline students.

But he adds that “government policy on performance monitoring, and the use to which the resultant league tables are put, could also have a perverse impact on grading and hence grade inflation and standards”.

He suggests that degree outcomes “should be removed from league table rankings altogether” – they are used as metrics in some domestic league tables – “but this would most likely be met with objection in a ‘consumerised’ higher education system where student information is central”.

And Dr Bachan adds: “The evidence also shows that this unexplained component has been present in UK higher education from around the academic year 2010-11, and it may be the case that the increase in tuition fees in 2012 may have also contributed to the rise in upper and first-class degrees as universities attempt to attract fee-paying students.

“Government policy therefore needs to be given more consideration before it is put into force as it too may be seen as encouraging inflationary practice.”

The report’s findings – and the sector’s wider review – come after Times Higher Education revealed how one university department discussed its share of good degrees and league table position just weeks before a moderation exercise raised dozens of student marks. A further analysis by THE also suggested that certain subjects may be fuelling the rise in firsts.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Tripling of fees could be reason for rise in firsts

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login