Timothy Garton Ash has written 10 books but notes that one – The File: A Personal History – “is the one people always mention and are touched by”.

The professor of European studies at the University of Oxford had spent time in East Germany in the years after 1978 and naturally attracted the attention of the secret police. When he got a chance to look at his own Stasi file after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he realised this disconcerting episode could form the perfect basis for a book.

“I did not hesitate for a moment,” he explained, “because the kind of insight that you can get from your own experience when documented by secret police is clearly unique. I was also able to see my informer’s files and my Stasi officer’s files and then, when I went to meet them, we had this unique relationship of the spied upon and the spy. I honestly believe that book gave a unique insight into how the secret police of a dictatorship works.”

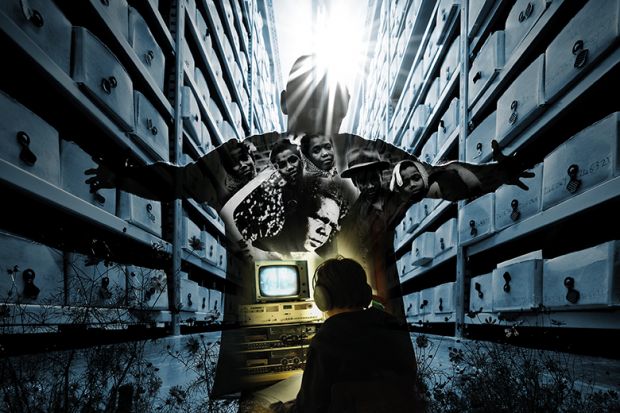

The File, published in 1997, was one of the first titles in a rapidly growing genre of historical titles that foreground personal experience, travelogue and the quest to find answers alongside archival research. More recent examples include The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance by Edmund de Waal, former professor of ceramics at the University of Westminster; East West Street and its sequel The Ratline by Philippe Sands, professor of laws at University College London; and Imperial Intimacies: A Tale of Two Islands by Hazel Carby (pictured below), Charles C. and Dorothea S. Dilley professor emeritus of African American studies at Yale University.

These titles have shared a slew of awards and outsold many more traditional historical monographs. At a time when the humanities are widely seen as being under threat, should more academics overcome their reluctance to put themselves at the heart of their writing?

Professor Sands said that, in his own field of international law, he has felt “increasingly concerned that we spend too much time talking to each other, rather than reaching across academic boundaries and also reaching the reading and intelligent general public”.

Like one branch of his own family, the great legal scholars Raphael Lemkin and Hersht Lauterpacht – who formulated the crucial concepts of “genocide” and “crimes against humanity” – came from the city of Lviv, now in the Ukraine. East West Street interweaves their stories with an account of how leading Nazis were brought to justice at Nuremberg in 1945-46. Although the result clearly differs from a standard monograph, Professor Sands stressed that he “could not have written my more recent books without decades of writing more classical scholarship, or the fruits of such scholarship as produced by others”.

Professor Carby’s Imperial Intimacies locates her memories of growing up in post-war London as the daughter of a Jamaican father and Welsh mother within the much longer and bloody history of relations between Britain and Jamaica. The narrative switches between the perspective of “the girl” she once was and the “I” of the adult researcher, “pitting memory, history and poetics against each other”.

Such an approach, Professor Carby once explained in an interview, provided the only way of doing justice to the range of issues she wanted to address: “If we are going to tell stories that involve us...conventional modes of writing...cannot possibly encompass the multiplicity of the tales that we want to tell. I also wanted to write within a framework that could create a sense of how different parts of the empire were intimately tied to each other, intimately dependent on each other.”

Mark McKenna, professor of history at the University of Sydney, made a similar argument about his own work. He had been examining the history of central Australia when he stumbled across a cold case: an Aboriginal man killed in 1934 by a white policeman at the sacred site of Uluru. His recent book, Return to Uluru, describes how he spoke to the families of both killer and victim, unearthed new evidence and came to fresh conclusions about the events and their implications for today.

“It’s easy for the first-person ‘quest’ narrative to appear feigned, clichéd or clumsy,” Professor McKenna admitted. As a result, “it has to be more than a convenient or fashionable literary device, it has to be the only way the writer believes they can do justice to the story”.

There were also issues of intellectual integrity. In books addressing highly contentious issues such as the treatment of indigenous Australians, Professor McKenna pointed out, “neutrality is never possible of course, or even desirable”. This meant that “honesty is crucial...if my experience is fundamental in explaining why I write, then it should be in the narrative – although lightly!”

But what do other academic historians make of such books? Do they see them as simply different from standard monographs, or as amateurish, misleading and perhaps even dangerous?

Philip Carter, research and communications officer at the Royal Historical Society, hoped that “academic history is now much more open to experimentation in forms and approaches to writing about the past, and that the personal narrative (the historian within and as part of the history) is appreciated widely – not least because it engages openly with questions of the role of the historian in creating their ‘personal’ version of the past”.

Nonetheless, Dr Carter went on, professional incentives tended to determine who could write what. “Experimental approaches within academia do seem to be the choice and preserve of the established academic who’s already covered the traditional monograph and article ground...the younger academic remains within the established structures of writing and publishing that build a career,” he said.

Other historians had more ambivalent feelings about such “experimental approaches”.

Sir Richard Evans, provost of Gresham College and former Regius professor of history at the University of Cambridge, enjoyed “reading history books constructed around a personal quest” and was worried that “treating ‘research’ as something that is only of interest to one’s fellow academics will inflict serious damage on the historical profession”. Yet he also believed that “outsiders who write history” can make significant mistakes in “neglecting the historical context, failing to ask the important questions, and positing connections and causal links that a rigorous professional training would have revealed as unconvincing...so we can’t use [their books] in teaching except to convey the excitement of research”.

When he reviewed East West Street in The Guardian, Sir Richard acknowledged that the book “pull[s] the reader into the story in a way that is as powerful as it is personal” but went on to ask: “Does it matter that Lemkin, Lauterpacht, [leading Nazi Hans] Frank and Sands’ family all have a connection with Lviv? Sands tries hard to make the connection mean something, but in the end it doesn’t…To the historian, it all looks very much a first draft.

“Why were the ideas of Lemkin and Lauterpacht accepted? Simply to tell the story of these ideas and the actions of their authors doesn’t answer the question. The concept of ‘human rights’ didn’t just triumph because of its inherent persuasiveness. Anyone who wants explanation rather than storytelling will have to turn elsewhere for an answer.”

Emily Michelson, senior lecturer in history at the University of St Andrews, recently read The Hare with Amber Eyes, which uses the collection of Japanese miniature sculptures once owned by Mr de Waal’s ancestors as a prism for exploring how the great Ephrussi banking dynasty was scattered and destroyed by the upheavals of the 20th century. Books such as this, she said, “can be marvellous for the study of history. They make it personal, vivid and compelling. I know that I never fully understood the scale of the First World War – the way it destroyed an entire way of life and left a generation bereft, not only from the death toll, but from the fact of surviving into a wholly unfamiliar world where their old connections and skills had no meaning, until I read The Hare with Amber Eyes.”

More generally, when she ventures outside her specialist field of the Reformation, Dr Michelson acknowledged that she “learned much more through fiction, creative non-fiction and drama than I would through reading Oxford University Press monographs”. Family memoirs and other non-academic historical writing could be “good for history as a discipline...in as much as a reader recognises through them that history is meaningful, that we haven’t yet found it all out or told all the stories, and that sources must be valued and preserved”.

What remained crucial for Dr Michelson, however, was that readers – and, even more, “government funding bodies” – understand that “historians are actually doing the bulk of that work, and are also enabling the memoirists by ensuring the preservation of the sources and writing the scholarly infrastructure that lets a memoirist reconstruct their story”. The danger was “if readers come away thinking that what historians do is just uncover cool stories from the past, and that memoirists do it better and with film rights”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?