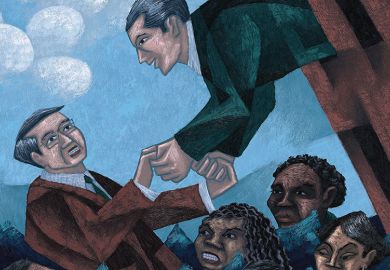

A Harvard University sexual assault case is alarming US higher education by laying bare how academics will still reflexively protect a star colleague even with a decade-long record of abuse complaints.

Five years into the #MeToo movement, the case against John Comaroff has grown notorious for the nearly three dozen Harvard colleagues who quickly signed and then retracted a letter backing the professor of African and African American studies.

“We’ve made so much progress with the #MeToo movement,” said Carolin Guentert, an attorney for the students suing Harvard over the case. “But we see, over and over again, that individuals’ instincts are often to not believe the people coming forward.”

Their case, filed in state court in Massachusetts, contends that Harvard knew of Professor Comaroff’s purported record of sexually harassing students when it hired him from the University of Chicago in 2012, and took no action against him when he allegedly persisted with the behaviour at Harvard.

THE Campus views: Bullying by supervisors is alive and well – now is the time to tackle it

The lawsuit is being brought by three doctoral students – Lilia Kilburn, Margaret Czerwienski and Amulya Mandava – who contend Harvard left them with “dismal job prospects” by failing to counter the immense reputational authority that Professor Comaroff holds over them and their field.

Harvard has placed Professor Comaroff on unpaid administrative leave for one semester, among other sanctions. But Harvard’s many failures in the case, the students argue in their complaint, include its repeated refusals to investigate their complaints until media attention forced the university to act.

Then, during the formal internal investigation that Harvard finally agreed to stage, the university let Professor Comaroff pick participating staff with an eye toward including those whose association with him would prove most professionally damaging to the plaintiffs, they said.

This included George Meiu, a Harvard professor of anthropology and African and African American studies, whose testimony during the university review hearing amounted to him confirming the layout of a seminar room. The university’s review eventually discounted much of Ms Kilburn’s harassment complaint in part because she could not precisely recall a specific wall against which she alleges Professor Comaroff assaulted her.

Professor Meiu obviously was not needed to describe the layout of a particular room at Harvard, Ms Guentert told Times Higher Education. But he was due to preside over Ms Kilburn’s exams and to decide whether she would be awarded her doctorate.

Professor Comaroff used his right to call hearing witnesses to include three additional scholars – Caroline Elkins, a professor of history and African and African American studies at Harvard; Sue Cook, former executive director of the institution’s Center for African Studies; and Peter Geschiere, a professor of anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. Those three also had no important value to the case, Ms Guentert said. But if not for their participation in the hearing they could have remained available to Ms Kilburn as potential advisers and mentors to replace Professor Comaroff.

A lawyer representing Professor Comaroff, Ruth O’Meara-Costello, contended otherwise. A key element of Ms Kilburn’s complaint is that Professor Comaroff, ahead of a planned research trip to Africa by Ms Kilburn, spoke in graphic and threatening terms about the risks she was taking, including the possibility of her rape and murder. The three scholars all had expertise on whether such a warning was appropriate, Ms O’Meara-Costello said.

“Professor Comaroff did not identify any professors or academics as witnesses who were not highly relevant to the claims that Title IX was investigating,” she told THE, referring to the 1972 federal law that prohibits sex-based discrimination in any education programme.

Ms Guentert said she could not speculate on why colleagues appeared so willing to assist the defence of Professor Comaroff, who denies all allegations of sexual harassment and retaliation.

“It’s entirely possible that some of these professors had a good relationship with Professor Comaroff, and that maybe they don’t want to believe that this is true,” Ms Guentert said. But, she continued, “they abdicated their responsibility by maybe not reading that letter closely, or only letting themselves hear one side of the story, or maybe not wanting to see what was happening in front of them”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?