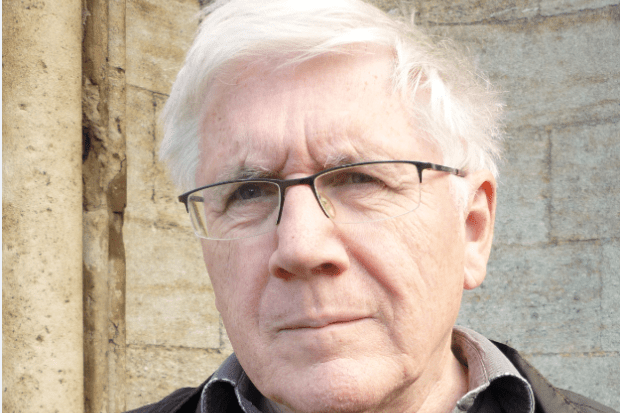

Raymond Geuss is emeritus professor of philosophy at the University of Cambridge. His latest book, Not Thinking like a Liberal, which details his childhood, education and early intellectual influences, is published by Harvard University Press this month.

When and where were you born?

Evansville, Indiana – my father’s home town – on 10 December 1946.

How did this shape you?

We moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1947, when my father got a job in a steel mill there. He, however, became seriously ill. This was a double blow because he could not work, and medical care in the US was expensive even then, so we were very poor. This experience left me disinclined ever to take comfort for granted or to think that cultural advantages come from nowhere. However, the years 1957 (Sputnik) to 1971 (devaluation of the US dollar) were a window of time during which good higher education was available even for someone without means.

Your new book explains how you were taught by Hungarian priests who had escaped persecution in Communist Europe at an elite boarding school outside Philadelphia. Did this education lead you towards philosophy?

The general direction of my intellectual interests was set by my father before I went to school. He was obsessed by two questions. First, he knew that as a Catholic he should believe in papal infallibility but could not, and so he circled around this issue incessantly. Second, how could the Catholic Church maintain itself in existence and retain its spiritual authority, given the extreme corruption of the clergy? These interests that he had in the nature of knowledge, the role of morality in history, and the conditions of stability of social institutions seem to me, in retrospect, to clearly prefigure my own.

You came from a religious family and your uncle was a priest. How did they feel about your rejection of religion?

The attitudes in the family to my rejection of religion ranged from grudging acceptance to murderous rage. In a way my situation was made easier by Vatican II, which was perceived in the family as a betrayal of traditional Catholicism. Feeling this way, they were not best placed to criticise me.

How do you define liberalism and why, from a young age, have you not felt the need to embrace it – particularly given that you were a student in New York in the 1960s, perhaps the heyday of liberalism?

I don’t think intellectual and historical movements can be “defined”; still most liberals preach the importance of the autonomous individual as the final judge of his (the masculine pronoun is no accident) own desires and interests, and a sovereign chooser. I would exactly reverse the second question: how could anyone in the “heyday” of liberalism in the New York of the 1960s fail to see that it was a complete failure? Consider: the great American liberal Kennedy invaded Cuba and threatened the world with nuclear war; he also oversaw the beginnings of the war in Vietnam, which was further prosecuted – using means such as massive defoliation of the countryside in Vietnam using carcinogenic chemicals – by the great liberal Johnson. Need I continue?

At Columbia, you were taught by Sidney Morgenbesser, so revered for his sharp witticisms that he was once dubbed the ‘Sidewalk Socrates’. Why was he so influential for you?

His mind was highly systematic – issues were never treated in isolation but always in a context of multiple connections they had with other issues – yet he had no single system into which everything was forced to fit. His humour was the expression of a deep understanding of the ultimate imperviousness of human life to discursive reason.

What prompted you to go to West Germany after your PhD? How did that experience change your outlook on philosophy?

After receiving my PhD in 1971, I was keen to leave the US, which I thought was a decadent country, addicted to violence, unable to rid itself of the continuing legacy of slavery, and lacking some of the basic institutions of a decent society – free, or even minimally affordable, healthcare, education, etc – with great economic inequality, and an antiquated 18th-century political system that was clearly no longer fit for purpose. In contrast, the new idea of pooling sovereignty on which the European Union rested represented one of the few glimmers of hope in that dark time. I was offered a job in West Germany and accepted because I was keen to live in Europe. I had been a student in Freiburg, in West Germany, in 1967-68. That academic year saw the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the assassination of Rudi Dutschke in Berlin and of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King in the US, “May 1968” in France – with a ripple effect in Germany – and the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the troops of the Warsaw Pact. Those events changed my philosophical attitudes, moving me both further to the left and in the direction of greater scepticism, but, by 1971, my basic outlook was already well established and hasn’t really changed since then.

Tell us about someone that you admire.

I admire Toussaint Louverture and Rosa Luxemburg for their energy, political astuteness and stoicism, and Rabelais for his literary originality and linguistic inventiveness.

What do you do for fun?

Since my retirement in 2014, after 40-plus years as a university lecturer, my whole life is nothing but fun. The two main things I do since I have retired are walk – two hours a day – and play the piano.

Will Russia’s war on Ukraine bring about a renewed appreciation for Western liberalism?

Perhaps it will, but it shouldn’t. Western liberal democracies, too, are perfectly capable of violating international law by invading independent countries that are members of the United Nations and trashing them completely. Think of Iraq. “Liberalism” always gets the benefit of the doubt. Faults of liberal regimes are always the result of inadequate liberalism; faults of other regimes are structural defects.

jack.grove@timeshighereducation.com

CV

1966: BA, Columbia University

1971: PhD, Columbia University

Taught at Columbia University, Princeton University and the University of Chicago, and at Heidelberg and Freiburg universities in Germany, before moving to the University of Cambridge in 1993.

Key publications include The Idea of a Critical Theory (1981), Morality, Culture, and History (1999), Philosophy and Real Politics (2008), A World Without Why (2014), Reality and its Dreams (2016) and Who Needs a World View? (2020). He has also co-edited two critical editions of works of Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and Writings from the Early Notebooks, and published two collections of translations/adaptations of poetry from Ancient Greek, Latin and Old High German texts.

Appointments

Marc Christensen has been named president of New York’s Clarkson University. Currently dean of the Lyle School of Engineering at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, he will take up the post in July, succeeding Anthony Collins on his retirement. “Marc’s passion for innovative teaching, collaborative multidisciplinary research, proven entrepreneurship, successful fundraising and community outreach is an excellent fit for Clarkson,” said Thomas Kassouf, chair of the university’s trustees.

Frances Bowen is returning to Queen Mary University of London as vice-principal for humanities and social sciences. She spent seven years at Queen Mary from 2011, rising to become dean of the School of Business and Management, before joining the University of East Anglia as pro vice-chancellor for social sciences. Colin Bailey, principal at Queen Mary, said Professor Bowen was “an outstanding academic leader, with a strong affinity to our values and mission”.

John McGreevy has been named Charles and Jill Fischer provost at the University of Notre Dame. He is Francis A. McAnaney professor of history at Notre Dame, and spent a decade as I.A. O’Shaughnessy dean of the College of Arts and Letters.

Mario Pinto is joining the University of Manitoba as vice-president (research and international). He is currently director of Queensland’s Gold Coast Health and Knowledge Precinct, having previously served as deputy vice-chancellor for research at Griffith University.

Raheel Nawaz has been appointed pro vice-chancellor for digital transformation at Staffordshire University. He is currently director of digital technology solutions at Manchester Metropolitan University, where he is also director of the Business Transformations Research Centre.

Aisha Jackson has been picked by the University of California, Santa Cruz as vice-chancellor for information technology. She is currently assistant vice-chancellor for academic technology and student success at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The University of Strathclyde has appointed Stuart Fancey as university secretary and Louise McKean as university compliance officer.