As A-level results were announced last month, it was heads of admissions at the UK’s middle-ranked universities who generally had the broadest smiles on their faces.

Initial data from Ucas showed that they had enjoyed the biggest rise in undergraduate recruitment, year-on-year, with the most prestigious universities experiencing more modest growth and the least selective institutions struggling to make gains.

With clearing now winding down and term starting soon, these trends have, if anything, become more pronounced.

On results day, 18 August, overall recruitment at UK universities with the lowest entry requirements had increased by 1.2 per cent on the same point last year. But, by Ucas’ final clearing update, published on 2 September, this had turned into a 2 per cent decline – equivalent to 3,900 fewer students entering this part of the sector compared with 2015.

This suggests that a challenging recruitment cycle for these providers was made only tougher by competition from more selective universities during clearing.

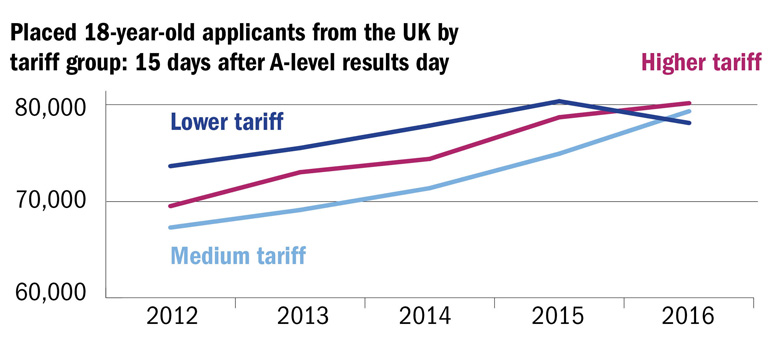

It is among 18-year-olds from the UK that the differences in recruitment trends are most pronounced. Ucas’ final set of clearing data shows a 2.8 per cent decline in enrolment at low-tariff institutions from this cohort, in contrast to a 5.9 per cent increase for middle-ranking providers, and a 1.9 per cent rise for elite universities.

Competition is tight at the bottom of the sector because the pool of domestic 18-year-olds is shrinking and the removal of student number controls allows more selective institutions to trade on their reputation and expand at less celebrated providers’ expense.

Medium-tariff institutions register rise

Meanwhile, at the top end of the sector, universities face a challenge because the proportion of students getting top A-level grades fell for the fifth year in a row; and institutions might not wish to relax their entry requirements too far for fear of jeopardising their league table standing.

Thus it is the middle-ranking universities that have been able to capitalise on the lifting of number controls, with declining grades pushing more applicants into their traditional territory.

As Sir Steve Smith, vice-chancellor of the University of Exeter and the chair of Ucas, put it on results day: “The squeezed middle has become the bulging middle.”

Ucas’ results day statistics were pored over by universities for signs of any change in European Union recruitment following the UK’s vote for Brexit, and the general consensus was that the existing upwards trend had continued, with enrolment up 10.8 per cent year-on-year.

By this month, however, the year-on-year growth had tailed off slightly, to 7.9 per cent, which could be seen as a sign of applicants opting not to take places via clearing once the referendum result had been released. The number of EU students applying directly through clearing, and therefore entering the Ucas process after the Brexit vote, was down 11 per cent compared with 2015, although this reflects a decline of only 80 students.

It may be that the full impact of leaving the EU will become clear only in the 2017 admissions cycle, but there are already warning signs around non-EU recruitment in the Ucas data. By the time of the final clearing update, international undergraduate recruitment was down by 0.8 per cent year-on-year, the first such decline in recent years and following several cycles of strong growth.

By the final update, overall sector recruitment via Ucas had tipped just over 500,000, up 1.3 per cent compared with 2015. But continuing demographic challenges and emerging overseas difficulties mean that clearing is only likely to become more important for universities as they look to fill their places.

The number of students placed via clearing was up 2.5 per cent year-on-year as of 2 September, with 42,580 students enrolling via this route. The most significant growth, however, was in placements of students who had applied direct to clearing, after the Ucas main scheme closed: this was up 6.7 per cent compared with 2015.

In contrast, the number of applicants using Ucas’ adjustment scheme, which allows students to “trade up” if they do better than expected, has slumped by 20.7 per cent, to just 920.

Full analysis of this year’s recruitment cycle will be released by Ucas in December.

后记

Print headline: Lower-ranked institutions squeezed in clearing