England’s higher education spending increased in the first year of £9,000 tuition fees and its financing system allowed it to “raise spending in difficult times”, unlike European rivals, but the country has the most expensive public universities in the world.

The developments are reported by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, whose annual Education at a Glance report includes data from England’s post-2012 system for the first time this year.

The UK is reported to have the fourth highest spend per student among OECD member nations, behind only Luxembourg, the US and Norway. The UK spent $24,338 (£16,016) per student in 2012-13, compared with the OECD average of $15,028, according to the OECD (figures that include spending on “core, ancillary services and R&D” and are converted into dollars using purchasing-power parity).

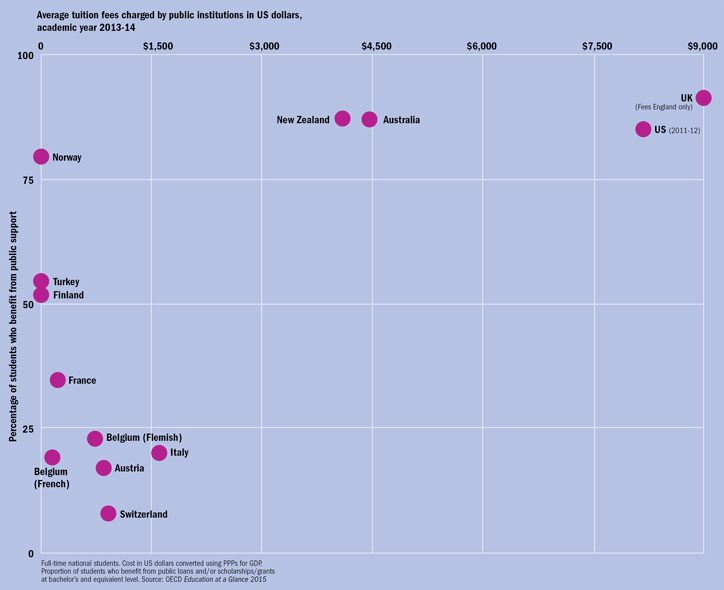

In terms of average tuition fees at public institutions, the OECD puts England top ($9,000), ahead of the US (about $8,000).

Andreas Schleicher, the OECD’s director for education and skills and a long-standing advocate of income-contingent loans in higher education, described England as “one of the few countries that has been able to accommodate larger numbers of students without seeing spending per student decline”. He contrasted this with the higher education policies of major European nations where fees are much lower or non-existent, such as France, Italy and Germany.

Mr Schleicher said that “the success of the UK in mobilising private resources, through…student financing, has allowed the system to raise spending in difficult times, which is not the case in many other countries”.

The UK now spends 1.8 per cent of its gross domestic product on higher education, up from 1.2 per cent in the previous year.

Asked about the big jump, Mr Schleicher said: “Relative to GDP, there have been two things: there’s been a decline in GDP and spending on higher education has been increased.”

However, the sharp rises in spending per student and in spending as a proportion of GDP since the trebling of fees may also prompt questions about the treatment of England’s loan funding in the report’s calculations.

At a briefing for journalists in London on 23 November, Mr Schleicher said that England’s financing system meant that the country had been able to avoid the “dilemma” experienced by France, Italy and Germany.

Tuition cost v state support: average fee compared with proportion of students who benefit from public support

These nations “say higher education is terribly important”, continued Mr Schleicher. “But they say we’re not going to put more public money into this, and we’re not allowing people to pay for it themselves.”

Those countries were experiencing “an expansion of the system and at the same time a lack of capacity”, he said.

Public sources finance 57 per cent of spending on higher education in the UK, below the OECD average of 70 per cent.

Mr Schleicher also said that “the steep rise in tuition fees that is for the first time reflected in our data in Education at a Glance hasn’t actually damaged participation [in the UK]. In fact, participation still seems to grow.”

He added that “in part this is because you back that up well – the UK comes out number one in terms of giving access to student support – access to loans, access to means-tested grant”.

“But that’s not a new story,” said Mr Schleicher, in reference to the fact that a new fees and student funding system was introduced in 2006.

Critics argue that it remains to be seen whether the government’s decision this year to scrap student maintenance grants and replace them with loans will harm access.

Mr Schleicher suggested that OECD data show that in terms of the wage premium for graduates, the social background and educational level of students’ parents in the UK explains a larger portion of the premium than in other countries.

But he also said that the “barrier” to social mobility was in schools rather than universities. “If you want to get more people into better tertiary education, you’re far better off creating the foundations for this in the schools system than by making university free,” he said.

On the balance of public and private funding, he said: “If I look at the data, I would think the UK – despite its heavy reliance on the private financing of higher education – has made a wise choice. It works for individuals, it works for government.”

Who’s paying: portion of GDP spent on higher education

| Country | % of GDP invested in tertiary education, 2012 | ||

| Public | Private | Total | |

| US | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| Canada | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| South Korea | 0.8 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| UK | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.8 |

| Australia | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| Japan | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| France | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

| Germany | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| OECD average | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

Note: Canada year of reference is 2011.

Source: OECD Education at a Glance 2015

后记

Print headline: ‘Wise choice’, OECD chief says of move to £9K fees