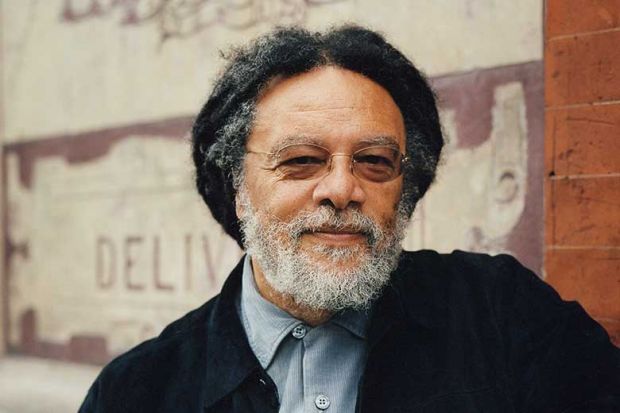

“Nothing beats being taken seriously,” said Paul Gilroy. “This is about as seriously as you can be taken.”

He was referring to the announcement that he is this year’s winner of the prestigious Holberg Prize, established by the Norwegian Parliament in 2003, for work that has “influenced and, in some cases, reshaped several fields and sub-fields, including cultural studies, critical race studies, sociology, history, anthropology and African American studies”.

Now professor of American and English literature at King’s College London, Professor Gilroy first came to fame with the publication of There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack in 1987, a book that set out to challenge the notion that race was “marginal to the normal processes by which British society has developed” and argued that class analysis had to be “substantially reworked in the light of its encounter with ‘race’”. Although the book has now become a classic, the immediate result, he recalled, was that “it was made very clear to me that my temporary contract of employment wasn’t going to be continued”.

So how had attitudes to scholarly work on race changed since then?

Today, Professor Gilroy acknowledged, “there is a greater degree of legitimacy awarded to those of us who want to specialise in these areas. I’m glad of that, but is that process complete? Not really, not from the discussions I have with younger scholars.” One had recently described to him, for example, “a meeting looking at candidates where they were told ‘race was interesting a few years ago, but not any more’.” “The archival and theoretical work in the field is somehow judged to be secondary or journalistic or identity politics,” Professor Gilroy said.

There had also been an exodus of British specialists in such topics. Professor Gilroy himself spent the period from 1999 to 2005 at Yale University because he thought he would be “taken more seriously there”, but had returned to the UK – somewhat ironically in light of Brexit – because he “wanted to be part of the intellectual life of this country and part of the scholarly culture of a new Europe that I thought was in the making”.

Debates about the decolonisation of the curriculum, in Professor Gilroy’s view, had been “helpful in purging some of the bad habits and default settings which have left so much of the archive of humanistic studies in the hands of people who have a tacit nationalist orientation”.

But, he added: “Educated people in the UK need to be much more extensively acquainted with the history of the imperial and colonial past of this country. Where that acquaintance is considered to be the ethnic property of black Britons, then we’ve still got a great deal more work to do.” Furthermore, there were still “some very respected and authoritative figures, often expatriate English voices, who argue it’s banal to make the kind of criticisms [of empire] that I make. The balance of forces is very divided.”

On the shortage of black professors and the challenges faced by ethnic minority students in British universities, Professor Gilroy saw no substitute for “looking in a really patient and detailed way at what people are studying, where they are studying and the pressures they are under”. He placed little faith in importing models from the US or “simply reaching for a diversity and empowerment agenda”, whereby “people are packed off to learn a new rhetoric to satisfy the award of Kitemarks”. He was equally sceptical about attempts to “match a curriculum to the incoming ethnic or racial or cultural character of students”.

The Holberg Prize is given to an outstanding researcher in the arts and humanities, the social sciences, law or theology and comes with NKr6 million (£530,000). So did Professor Gilroy have any plans as to what to do with the money?

He said he suspected that he would give some of it to organisations whose work reflected a central aspect of his research. One possibility was the charity Inquest, since it “works with families of people who have been killed following contact with the police or in custody. Their activity connects up with arguments about the varying value assigned to the different categories of life along racial lines.”

But the award also meant something else to Professor Gilroy. Several of the earlier laureates have also made important contributions to the study of race, he said, including Marina Warner, Natalie Zemon Davis and Ian Hacking, although he said that he suspected that none have been a “descendant of Atlantic slaves” like him.