Shortly before prime minister Boris Johnson announced the first national lockdown on 23 March 2020, Michael Ward realised that “something extraordinary was happening”.

A senior lecturer in social science at Swansea University, he had hitherto worked on how masculinity is mutating in post-industrial societies. He was also a great admirer of the Mass Observation project, which tracked the attitudes of ordinary people from the late 1930s to the mid-1960s. As Covid-19 began to bite, therefore, he decided to respond immediately and “record for posterity how society was being changed at a time of great upheaval”.

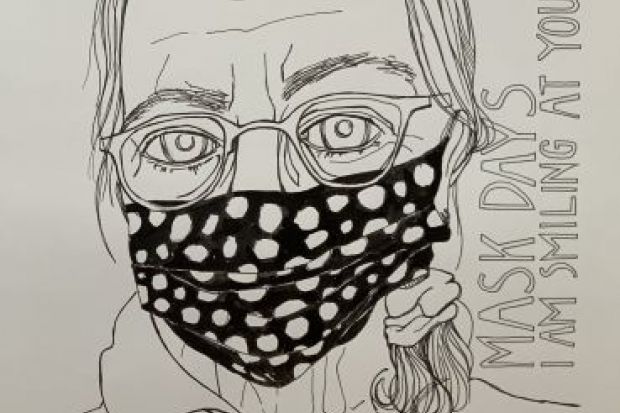

Dr Ward announced on Twitter that he was seeking first-hand accounts of living through the pandemic, thinking he would get replies from “a dozen people who know me, and I would keep it going for a couple of months”. In the event, his tweets got wide coverage on the BBC and the CoronaDiaries project now brings together 750 pieces of material from 182 participants aged 11 to 89, and living in countries ranging from Lithuania to Canada to Japan. Some had long kept a diary, but the vast majority created material especially. Much came in the form of artworks, blogs, dream logs, poems, social media posts, songs and TikTok memes, even playlists and a cross-stitch sampler.

The whole collection, said Dr Ward, formed “a longitudinal picture” from all walks of life, from cleaners to NHS consultants, people in rural areas who spent a lot of time in swimming pools last summer and others struggling to home-school children in a two-room flat”. It thus provided “very in-depth, qualitative data and very rich, thick descriptions of lives”, showing, for example, “how quickly we adapted to the surrealness of everyday life”.

A 19-year-old woman working in a care home, for example, described how “it felt like the nation, along with the rest of the world, was cast in a dystopian film. The police were akin to George Orwell’s Party members. It became part of their duty to pull cars and question the purpose of the driver.” Yet even those who wrote about the news and “wanting to throw something at the TV”, noted Dr Ward, might “write the next day about baking a cake”.

Since he was unable to secure funding from either the Economic and Social Research Council or the British Academy, he had kept the project going single-handedly alongside his day job, taking advantage of the fact he lived alone to devote all his spare time and energy to what “felt like something which was bigger than me, something I had to do”. Two books and other academic publications are in the pipeline.

When he embarked on his “reactive study”, however, Dr Ward had “no thoughts of an archive in a year’s time”. Yet the physical collection is now held in Swansea’s Richard Burton Archives. Meanwhile, student volunteers have helped prepare and anonymise the material produced by the 150 contributors who agreed it could be made public in the online digital collection. This was launched on 23 March, the anniversary of the first lockdown.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?