With the changing scope of federal regulations and increased scrutiny regarding sexual assault and harassment on university campuses, more and more institutions in the US are strongly discouraging, and even banning, consensual romantic relationships between students and faculty members.

But what about faculty-faculty relationships, or faculty-administrator relationships?

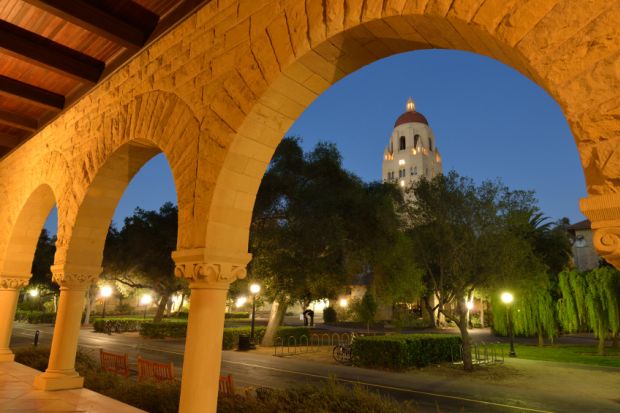

An ongoing legal case resulting in a dean’s resignation from Stanford University raises questions about what policies or best practices govern employee romance. Experts say that while these relationships tend to be too specific and fluid to fall under any general policy, involved parties should proceed with caution and avoid pairings that may be, or even appear to be, exploitative or allow for favouritism.

Earlier this week, Garth Saloner, dean of Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, announced that he was resigning, due in part to a lawsuit against the university brought by a former professor – one who happened to be the estranged husband of the woman the dean is dating, another professor at the business school, Inside Higher Ed reported.

James Phills, who was let go from Stanford this year, alleges discriminatory treatment by the university due to his entanglement in the dean’s love life. Stanford denies the claim, saying that Phills – who had been a non-tenured faculty member since 2003, several years after his wife was appointed to a tenured position – was terminated for failing to return after multiple leaves of absence to work in Silicon Valley. The university said in a statement that those leaves were “beyond what is normally allowed by university policy”, and that Phills “ultimately chose to continue his more lucrative employment at Apple”.

Citing increased media attention surrounding the suit, and its potential to distract from the business school’s mission, however, Saloner announced that he’s stepping down at the end of the academic year.

So did Saloner do anything wrong? Not according to Stanford, which, unlike lots of universities, actually has a policy governing faculty-faculty and faculty-supervisor relationships. The policy doesn’t ban these relationships outright but says that romances “between employees in which one has direct or indirect authority over the other are always potentially problematic. This includes not only relationships between supervisors and their staff, but also between senior faculty and junior faculty, faculty and both academic and non-academic staff, and so forth.”

The policy says that where such a relationship develops, the person with greater authority must recuse himself or herself from matters involving a romantic partner to ensure “that he/she does not exercise any supervisory or evaluative function over the other person in the relationship”. Where such recusal is required, the recusing party must also notify a supervisor, department chair, dean or human resources manager, so that person can ensure adequate alternative supervisory or evaluative arrangements are put in place.

Stanford says that Saloner properly disclosed his relationship from the beginning, and that others at the university took responsibility for final decision-making matters about Phills and his spouse.

Still, adhering to policy didn’t inoculate Saloner from being implicated in a lawsuit, or the related media scrutiny – including a story in The Wall Street Journal. And outside experts said that they weren’t surprised, since these relationships transcend regulation. Instead, experts said, best practices should be applied.

Herman A. Berliner, former provost at Hofstra University, said that he pushed hard to establish the institution's policy prohibiting romantic relationships between employees and students where a supervisory or evaluative relationship exists. Hofstra also has a policy in which an employee can’t supervise a faculty member when they are in a relationship.

Policy notwithstanding, it's “very hard to prohibit personal relationships, especially between colleagues”, he said. That’s in part because faculty members enter and leave the administrative ranks more fluidly than they do in other sectors.

“The faculty member in the next office could easily be the next department chair or dean or head of the faculty personnel committee,” he said. “Being a supervisor in higher education is often more fluid than in many other industries. How in situations like this, or just between colleagues, can you prohibit relationships, even if those relationships could ultimately be problematic?”

From the faculty perspective, the American Association of University Professors also has no policy regarding faculty-faculty or faculty-supervisor relationships. Anita Levy, associate secretary for tenure, academic freedom and governance, said that the issue rarely, if ever, comes up.

Michael Olivas, William B. Bates Distinguished Chair in Law at the University of Houston Law Center and director of its Institute for Higher Education Law and Governance, and former general counsel for the AAUP, said that’s probably true, and that cases such as the one at Stanford make news because they are rare.

“You can’t fully lay out every single possibility that’s going to occur,” he said. “But there are interlocking sets of principles that should govern our behaviour.”

Berliner took a similar view, saying that there’s no “perfect solution”, but that “you need to rely on the professionalism of the individuals involved”.