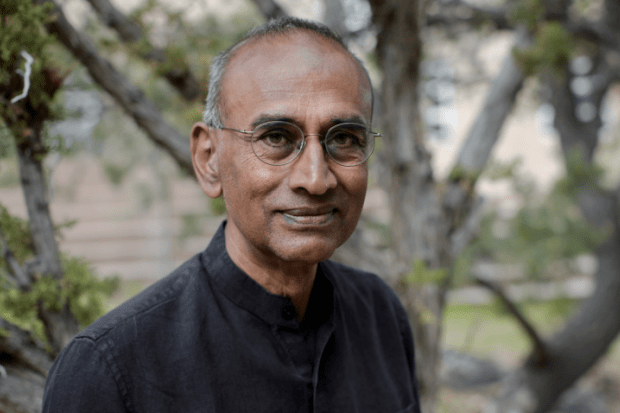

The Nobel prize-winning biologist Venki Ramakrishnan has said he might not have come to the UK if the current “unfriendly” visa regime for migrant scientists had been in place.

“I had to take a huge pay cut to come to Britain – about 40 per cent, but it was closer to a 50 per cent cut once you factored in higher costs of living,” explained Professor Ramakrishnan on his move from the US to Cambridge’s famous Laboratory of Molecular Biology 25 years ago. “If I’d have felt that this was a relatively unfriendly country that didn’t appreciate me, I might have said ‘Why should I give up my high-paying job to come to Britain?’” he told Times Higher Education.

Nowadays, visa fees are “out of step with competitor countries – they are really too high”, said the India-born scientist, who won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry a decade after moving to the UK, while the NHS surcharge recently rose by 66 per cent, to £1,035 a year.

“If you want to be a global leader in science, you can’t put up these unnecessary barriers,” continued Professor Ramakrishnan, who noted that “these barriers weren’t there when I arrived in Britain”.

Though it was not a great financial move, his transfer to the Medical Research Council’s flagship laboratory eventually came about because he considered it to be “a workers’ paradise” in terms of its research culture, access to world-class talent and rich international connections, he explained. “You spend most of your waking hours at work, so that’s why it’s good to be here,” he reflected.

Three years outside the European Union’s Horizon Europe research funding programme since 2021 had, however, made things much tougher, said Professor Ramakrishnan, whose five-year stint as president of the Royal Society from 2015 was dominated by concerns about post-Brexit science arrangements. “There has been a lot of additional bureaucracy for science that we didn’t have before,” he explained, adding that he “cannot see any benefit of Brexit whatsoever”.

Though the UK rejoined Horizon in January, he said he was unsure about whether lasting damage had been done. “The academic community has worked really hard to prevent the worst effects of Brexit, to maintain scientific exchanges and [fight] the perception that the UK is isolated,” he said.

“I don’t know if [being outside Horizon] will have huge ill effects – but, if it doesn’t, that’s only because the scientific community has worked harder than ever in difficult circumstances.”

When Professor Ramakrishnan turned 70 in 2022, he became increasingly struck by what he calls the “explosion in ageing research” – a subject he covers in his new book Why We Die: The New Science of Ageing and the Quest for Immortality, published in late March.

Having spent decades in what he calls “ageing-adjacent research”, the Nobelist felt he was well positioned to scrutinise the science in this much-hyped field, in which 300,000 articles have been published in the past 10 years: “I don’t have any skin in the game – my lab doesn’t study ageing, but our field is so fundamental that it is central to things like illness and ageing.”

While he said that he saw “very real breakthroughs in our understanding of ageing”, Professor Ramakrishnan admitted he was “sceptical” that anything would push human lifespan beyond natural limits, which is “probably about 120 years”. Some anti-ageing gurus believe, for instance, that science’s ability to “cure ageing” means the first person to live to 1,000 has already been born.

“Even though many more people are living past 100, no one has surpassed 120 for a long time,” explained Professor Ramakrishnan, noting that the last was a French woman who died in 1997 aged 122. More pertinently, he also examines in the book whether society would want its population to live routinely past 100, even if this is the dream of “Californian billionaires who love their lifestyles and don’t want the party to end”.

Anti-ageing research might be incredibly useful if it were to help people live more healthy, productive and happy lives, he insisted, though that also raised the tricky question of whether they would have to work until they were much older. That is a particularly pertinent question for academia, in which some universities – including Oxford and Cambridge – have set compulsory retirement ages.

“I’m planning to retire next year, but I do think the combination of tenure and the abolition of retirement ages isn’t a good one – you cannot have one without the other,” said Professor Ramakrishnan, referencing researchers who “hang around forever and whom you can’t get rid of”.

“You’ll get people [in their seventies] who claim they are producing the best work of their lives, but I don’t think the record shows that is true – you’re not as bold or imaginative as you were at 35,” he said, adding: “Senior people have a tremendous amount to bring to research, but they can play different roles – bringing young talent to their labs, working an advisory role or public service.”

Even in the case of a Nobelist, that was still true, he admitted. “My team is still publishing in top journals, but I don’t pretend that’s down to my brilliance – it’s because I have some really bright people around me.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?