The increasing tendency for academics to want to continue working well past 60 has provoked a fierce debate in recent years, with the potential impact on younger generations of scholars a central part of that discussion.

So what can data tell us about which countries have “younger” academic workforces, and to what extent is this linked to deliberate policies to maintain a healthy pipeline of talent into universities?

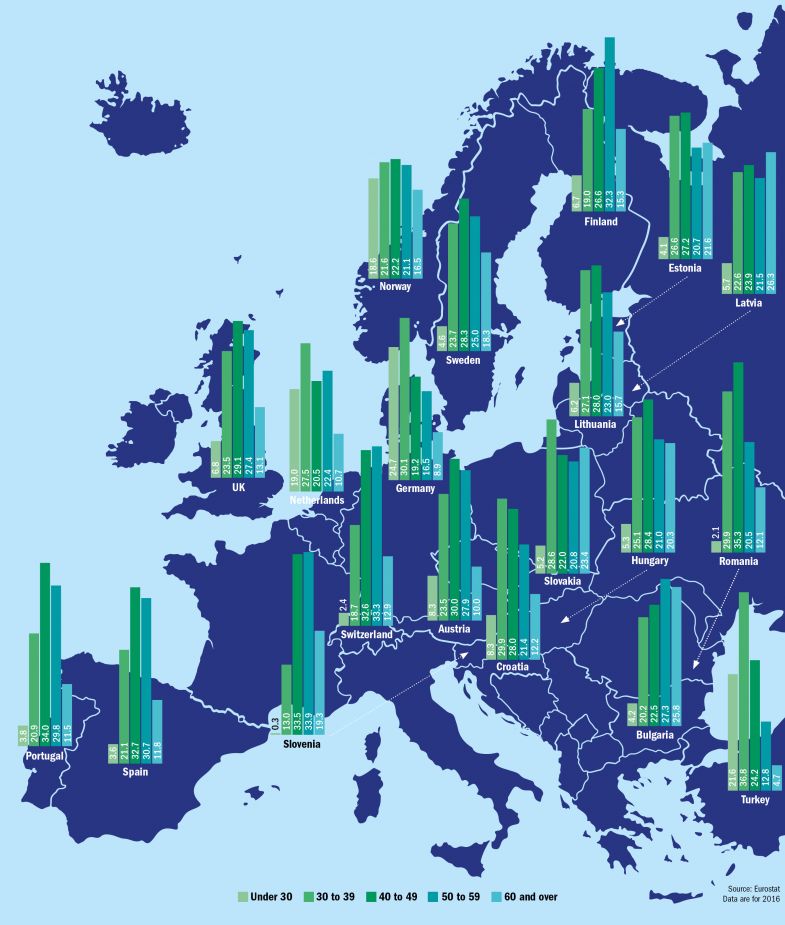

One place to attempt to make comparisons is Europe, where the European Commission’s statistics agency, Eurostat, publishes data on the ages of academic staff in countries inside and outside the European Union.

It shows a huge variation among nations, with academic staff aged under 30 making up less than 5 per cent of the workforce in several countries but more than 15 per cent of staff in other places, including Germany (where a quarter of staff are under 30) and the Netherlands (19 per cent).

Many countries in eastern Europe appear among those with the smallest shares of young academic staff, but there are clear exceptions. For example, Croatia has one of the higher shares of young academics (8 per cent) coupled with a relatively low proportion of staff aged 60 and over (12 per cent), while Switzerland’s share of young staff members is below 3 per cent.

A small share of the youngest academics does not always mean a low proportion of scholars working past 60, either. In Romania, just 2 per cent of academics are under 30, but still only 12 per cent are 60 and over. And Norway has a relatively high number of young academics (19 per cent under 30) yet also has a large share aged 60 and over (16.5 per cent).

So what is causing the difference in these countries: are there deliberate policies at work, or is it simply a product of different approaches to tenure and employment contracts?

According to Thomas Jørgensen, senior policy coordinator at the European University Association, the extent to which PhD students are classified as staff in universities might have a bearing on the statistics for younger academics.

The large shares of staff under 30 in Norway, the Netherlands and Germany were likely influenced by this, he said, adding that it was typical in Germany to insist on PhD students being called “doctoral candidates…because they are [deemed to be] staff”.

This factor might feed into the share of academics aged between 30 and 39 as well, although Dr Jørgensen suggested that a more significant factor influencing staff numbers in this age group was the amount of postdoctoral research funding that was available.

At the other end of the scale, he said, retirement policies were likely to be a major factor in explaining why many eastern European countries had much larger shares of academics over the age of 60.

“In some countries, there is simply no retirement age; you research until you drop,” Dr Jørgensen pointed out.

The ages of academia: age distribution of academic staff across Europe

Marek Kwiek, director of the Center for Public Policy Studies at the Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, explained that pension entitlements have traditionally not been as good in eastern Europe as they are in western Europe, in effect forcing academics to continue working.

Nevertheless, some factors that had helped to create an older academic workforce in parts of eastern Europe were now changing, he continued, while the increasing use of research assessment was also throwing a spotlight on the issue.

“While some older academics are highly productive, there are also unproductive researchers in this academic cohort. Overall, assessment schemes tied to institutional funding lead to closer scrutiny of all age cohorts,” Professor Kwiek said.

Mirroring these developments, some research funding in eastern Europe is now being “directed specifically to young academics, which slightly increases the attractiveness of the academic profession”.

The difficulty of attracting and, crucially, retaining this next generation of researchers had always been another major explanation for the older workforce profile, said Professor Kwiek.

However, are the factors that make academia attractive to the next generation always under the control of universities and policymakers?

To a large extent, said Dr Jørgensen, the number of people attracted to academia depended on the salaries and working environments that were available compared with those to be found on different career paths.

This might vary by disciplinary area. For example, alarm bells have been sounded recently in computer science departments because of concerns that those specialising in artificial intelligence are being enticed to work in the corporate sector, leaving a paucity of scholars coming through to teach the next generation of students.

“Our societies have become more research intensive, so there are alternative research careers – and you see this in artificial intelligence,” Dr Jørgensen said.

Universities could attempt to counteract such pull factors, but their success might be linked to the autonomy and freedom that institutions have on staffing issues.

“In some places, you can do very little because you don’t have the autonomy,” Dr Jørgensen said. “In some countries, you have a system that decides what counts in terms of research assessment and career progression, and that doesn’t make it easy for universities to be flexible about making careers meaningful and attractive.”

Professor Kwiek said that higher education in Europe had a challenge in attracting the younger generation given that employment in universities had in many respects become much more like the corporate world.

“The academic profession has traditionally been relatively well paid and relatively free in its time distribution,” he said, but over the years both these advantages have been slowly whittled away.

“All past advantages of academic work are gone – and all past disadvantages of corporate work are [pervasive] in academia. The boundaries get blurred – but salaries for young academics are uncompetitive.”

Professor Kwiek added that making higher education attractive through improved pay, better conditions and, above all, ensuring that it remains a “unique” place to work was vital to maintaining dynamism in the sector in the long term.

“Now that academic work increasingly resembles corporate work (with stress, funding pressures, publication pressures, admin requirements; teaching and research being assessed, with short contracts etc), there seems [less] chance [for universities] to have young top-class minds in Europe.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

后记

Print headline: New blood: which nations’ academies are most youthful?