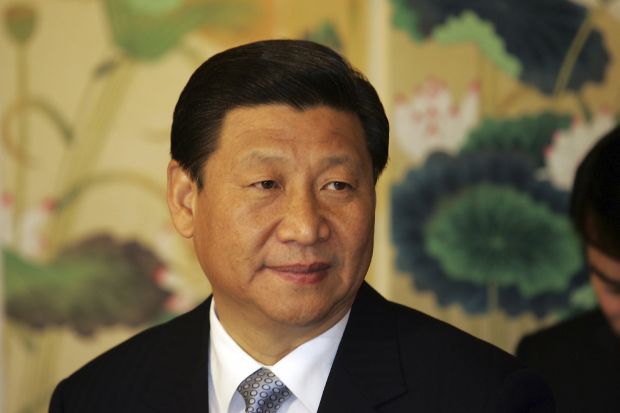

From his itinerary, you might assume that Xi Jinping is a big fan of the British university tradition. China’s president is set to visit no fewer than three universities during his state trip to the UK this week. On Wednesday, Imperial College London; Thursday, University College London’s Institute of Education for a conference on Confucius Institutes; and then on Friday, the National Graphene Institute at the University of Manchester.

But would Xi actually want any of these institutions, with their pesky autonomy and freedom of expression, in his own country? Since he came to power, a plethora of reports have suggested that the screw has been turning on universities and intellectual freedom in China.

Shortly after Xi’s accession, a party communiqué known as “Document 9” came to light that has set the agenda for the following two years. It raised the alarm about supposed Western “infiltration” of China’s “ideological sphere”. One passage singled out “public lectures, seminars, university classrooms, [and] class discussion forums” as hotbeds of dissenting thought.

The pressure on academics was stepped up in late 2014. In December, Xi urged more “ideological control” of universities and further teaching of Marxism. Early the next year, the education minister said that he wanted to ban university textbooks that promoted Western values. Another directive – Document No 30 – reportedly demanded that campuses be swept of Western, liberal ideas. A party investigator claimed that universities had been infiltrated by foreign forces. Only last week, Beijing city government announced that it would plough $31.5 million (£20.3 million) into the teaching of Marxism in universities.

It’s hard to imagine Imperial, UCL or Manchester thriving in such an environment. For a start, the best researchers could simply up sticks and leave for more liberal climes.

But while the West likes to believe that intellectual freedom and top research must go hand in hand, are things really this simple? It is surely the case in the most controlled areas, such as politics and recent history, but what about science?

For all its paranoia about Western values, the Chinese government places huge rhetorical faith in science. Hu Jintao, Xi’s predecessor, championed the dry concept of China’s “scientific development”. And huge research and development investment over the past decade seems to be having an impact: China overtook Japan in Times Higher Education’s latest university rankings.

But if the “ideological sphere” is tightly controlled in some areas, what is to stop such doctrinaire thinking spilling over and stultifying scientific research?

In The Three Body Problem, a sci-fi novel by the Chinese writer Liu Cixin set during the Cultural Revolution, the astronomer protagonist is prevented from performing an experiment because of the counter-revolutionary connotations of firing a powerful radio beam at the red sun. Even using the term “sunspot” (literally “solar black spot” in Chinese) is prohibited, because black was the colour of those who opposed the revolution.

For all the recent tightening up, Xi’s China is very relaxed compared with the hyper-politicisation of the Cultural Revolution. But still, sealing off scientific enquiry from political pressures may not as simple as it sounds.

Xi seemingly wants to have his cake and eat it. The Communist Party desires top quality universities, with their attendant economy-boosting research, but without all the other things that have historically gone with them in the West: ideas that challenge authority, independent student movements and gadfly academics.

It may be possible, but China’s universities will have to become even better (and remain quiescent) before we can conclude that the Party has succeeded.