One of the most significant changes to emerge from last week’s spending review is the creation of a £1.5 billion Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), which by the end of the decade will account for about 10 per cent of research spending, sector commentators have said.

The surprise creation of the fund, which will “ensure UK science takes the lead in addressing the problems faced by developing countries whilst developing our ability to deliver cutting-edge research”, means that there could be major subject winners and losers over the next five years.

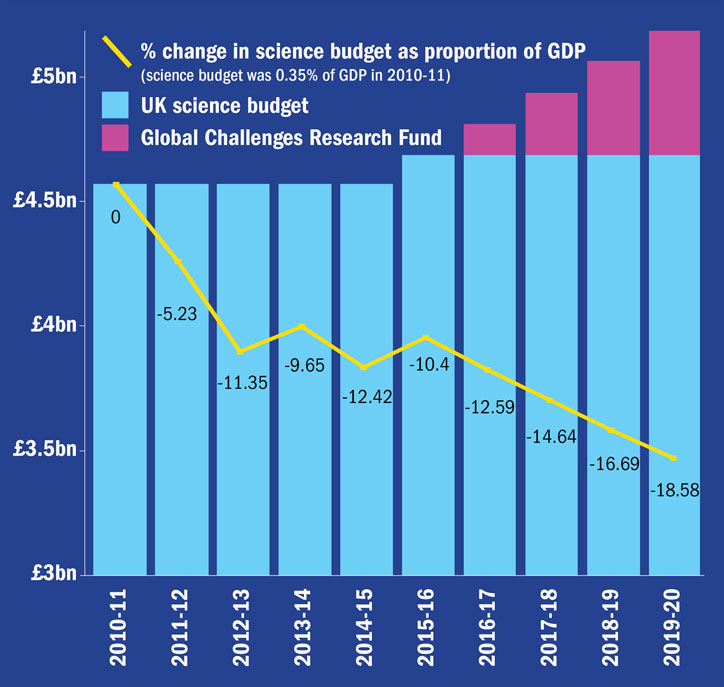

On 25 November, the chancellor George Osborne announced that the research budget would be protected in real terms until the end of this Parliament, having been frozen in cash terms since 2010, in what was welcomed by many as a better than expected settlement. The current annual allocation will rise from £4.7 billion to £5.2 billion by the end of the Parliament.

But the cumulative extra £1.5 billion this creates (from 2016-17 to 2020-21) will go to the GCRF and will “predominately” be distributed by the research councils, according to a spokeswoman for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

BIS has not yet released details about how the fund will operate, exactly what the challenges will be or who will make the decisions.

But according to a new aid strategy published on 23 November by the Department for International Development, the fund will “harness the expertise of the UK’s world leading research base to strengthen resilience and response to crisis”.

Research aid: budget up, but percentage of GDP falls

“Funding will include support for research on challenges like beating antimicrobial resistance and protecting animal and plant health, and emerging viral threats in developing countries,” it says.

The strategy also sets out plans for a £1 billion Ross Fund, which will “tackle the most dangerous infectious diseases, including malaria”.

Stephen Curry, professor of structural biology at Imperial College London and a member of the campaigning group Science is Vital, said much depended on how the GCRF would operate. “The question, then, is how is that going to be allocated? Can you [apply] for curiosity-driven funding? What’s the definition of a development challenge?” he said.

In his speech, Mr Osborne also committed to implement the recommendations of a review by Sir Paul Nurse, president of the Royal Society, into the functioning of the seven research councils. His report advises the creation of an overarching body, Research UK (RUK), to coordinate strategies and communicate with government.

Kieron Flanagan, senior lecturer in science and technology policy at the University of Manchester, said that this review was arguably a greater danger to smaller disciplines unlikely to receive money from the new fund. “Niche disciplines that have very different demands from big science…it’s very difficult to know how their voices will be heard in the new system,” he said. Of the GCRF, he said: “It sounds to me that the RUK chief executive and board of RUK will be setting this.”

The extra £1.5 billion for the fund will come from the budget for foreign aid. The government has pledged to spend 0.7 per cent of gross national income on such aid, and so counting the GCRF as part of this effort will help it to reach that goal.

后记

Print headline: Winners and losers from the new global challenges fund