I have achieved the impossible: I agree with Donald Trump. I have not become a friend of racists, or an enemy of immigrants. I continue to abhor trashy capitalism, crass nationalism, vulgar misogyny, monstrous egotism and brazen nepotism. But Trump is right to say that Confederate monuments should stay where they are.

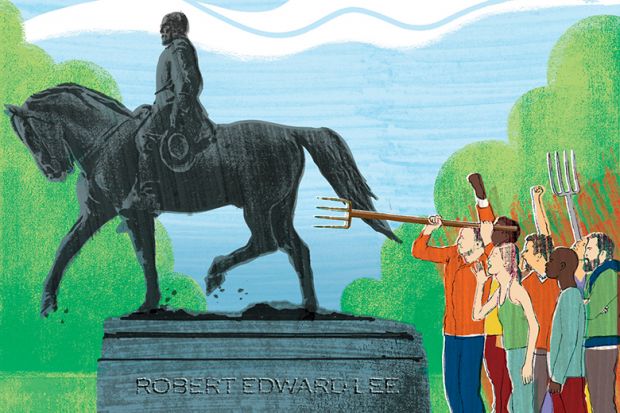

The problem of what to do with them has convulsed the US since recent violent protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, over a proposal to remove a statue of sometime Confederate generalissimo Robert E. Lee.

I saw the country’s most spectacular assemblage of memorials of Civil War heroes when I went to the University of Richmond, Virginia, the old capital of the Confederacy, to give, improbably, a business school lecture about leadership. The vast bronzes that dignify the city’s main boulevard evince splendour as works of art and value as documents of history. Statues of warriors commonly falsify war by misrepresenting it as glorious. Richmond’s, however, represent an episode of equally deep significance for understanding the past of the US: the defiance of the South after the long period of repression – mislabelled “reconstruction” by the invaders – that followed the triumph of the Union.

Nostalgia for a supposed antebellum utopia of Southern gentlemen, delicately nurtured belles and contented slaves is, like most popular reconstructions of the past, risibly mythical, but no one can know this country without taking it into account. Reconstruction nourished it and gave the sons and daughters of the Confederacy a cause. When they recovered autonomy and prosperity, they invested in a cult of their own “honoured dead”.

Distaste for the Union dominated regional politics as long as the distinctive economic profile of the South lasted. That era ended in the 1960s, but its resonances are still around, in resentment of “the Washington establishment” and vindications of states’ rights. Politicians neglect them at their peril. Ordinary people evoke them with conflicting passions of pride and prejudice, reverence and revulsion.

The statues that recall this past and explain this present do not belong only to one constituency. As works of art and lieux de mémoire, they are part of the history of the whole country – of the people who deplore the individuals they celebrate, as well as of Southern particularists. By clamouring to topple and trash them, liberals resign them into the hands of the mad minority of racists and white supremacists who have no genuine proprietary claim to them.

We should not let partisans monopolise any part of the past. Plinths elevate heroes, and it is in the nature of heroism to be equivocal. Saints are universal, but heroes are always partial. One side’s hero is another’s villain. If we are going to build societies of peace and consensus, we have to accept each other’s villains as elements of our common, often conflictive, past. I have no fear of statues, but I feel frightened when I hear my former colleague, the admirable scholar of Black Power, Peniel Joseph, denounce Confederate statues as “un-American”. The Ugly American is as American as American Beauty. We have a name for anyone who thinks that his or her version of America is the only valid one and who wants to suppress other people’s interpretation: hands up all those who want to erect a statue to Joe McCarthy. It seems an especially vile abuse of the ethic of victory to suppress the self-consoling arts of the victims of defeat. “In victory,” as someone once said, “magnanimity.” The University of Texas at Austin and Duke University have spirited away controversial statues. Elsewhere, overzealous students have vandalised them.

Confederate monuments, of course, commemorate racists and slavers. But so do almost all images of the 19th century. Abraham Lincoln was, in the strictest sense of the word, a racist, who thought racial differences made equality impossible. Few characters are so irremediably evil as to deserve the modern equivalent of burning in effigy. Trump displayed rare insight when he asked whether George Washington and Thomas Jefferson would succumb to the same irrationality as topples Robert E. Lee and his fellow Confederate general, Stonewall Jackson.

In mature democracies, we ought to be able to accept the whole of our histories, with the conflicts and contention, the good and ill that are strands in the experience of every people. Monarchists and Irishmen can contemplate Oliver Cromwell outside the Palace of Westminster without rancour. Finns all seem to like the tsarist monument that adorns Helsinki’s waterfront. Anti-imperialists in Barcelona or Oxford can host Columbus or Cecil Rhodes as stone guests without fearing the fate of Don Juan. A Jew can blink at a wayside crucifix. Like many Western liberals, I have a bronze bust of Napoleon in my study, without committing to improper admiration for that dictatorial warmonger.

Statues are made of the kinds of sticks and stones that cannot hurt us, but can remind us of the lessons and legacies of the past. You cannot obliterate history by wrecking its relics, immuring them in museums or censoring their significance with tendentious official “contextualisation”. Every time you do so, you alienate citizens, empower partisans and deepen divisions.

My next outside lecturing engagement is at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Will the statue of Lee still grace “Emancipation Park” (formerly “Lee Park”) when I get there?

Felipe Fernández-Armesto is William P. Reynolds professor of history at the University of Notre Dame in the US.

后记

Print headline: Trump is right: let Lee be