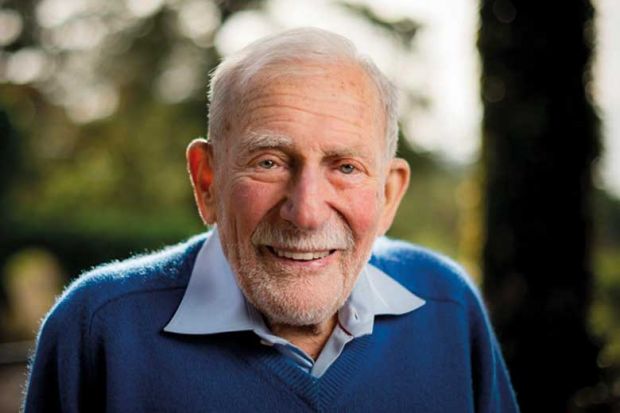

A world-class oceanographer who played a crucial role in the Allied war effort has died.

Walter Munk was born in Vienna in 1917 but was sent to New York at the age of 14 to work in banking. When this proved uncongenial, he took a degree in physics (1939) followed by a master’s in geophysics (1940) at the California Institute of Technology. After taking a summer job at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, in order to pursue a romance in La Jolla, he decided to do a PhD there.

An American citizen since 1939, Professor Munk enlisted in the army when war broke out but was soon recalled to Scripps to work at the new US Navy Radio and Sound Laboratory. He was involved in planning Allied amphibious landings and developed a technique for predicting when wave conditions were most auspicious. This was adopted in the Pacific and Atlantic theatres of war, and also used to determine that the high waves faced by troops during the Normandy landings were manageable.

After the war, Professor Munk returned to Scripps to complete his PhD (1947), joined the faculty and soon established himself as an exceptionally bold and wide-ranging oceanographer. He made major contributions to our understanding of the wobble of the Earth's rotation and tidal energy. He used acoustics to estimate ocean temperatures and thus the effects of global warming. He took part in an expedition to the Pacific in preparation for the testing of a nuclear bomb and even trekked across the Soviet Union to an oceanographic station near the Black Sea at the height of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Both a deep-sea worm and a pygmy devil fish are named after him.

A new branch of what became the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (a division of Scripps) was built on a La Jolla campus in 1959-63 and later formed the nucleus of the University of California, San Diego. Professor Munk was actively involved in the design of the institute and became its first director. He also retained close links with the US Navy, advised the Pentagon as part of the Jason group of elite scientists and retained until his death his Secretary of the Navy chair in oceanography.

Scripps director Margaret Leinen described Professor Munk as “a guiding force, a stimulating force, a provocative force in science for 80 years” who “never rested on his accomplishments [but] was always interested in sparking a discussion about what’s coming next”. He died of pneumonia on 8 February and is survived by his wife Mary Coakley Munk, two daughters and three grandsons.