Colonialism’s indelible mark continues to affect how Indian history is understood, taught and practised.

The idea of colonised nations as devoid of a “historical past” (or, at least, one that could be properly interpreted) became part of an aggressive agenda that glorified imperial agents as harbingers of progress, modernity and civilisation. The impression of a “timeless” India, whose people privileged afterlife over worldly existence, was a powerful instrument of imperialism. Britons castigated the native populace as negligent towards history and therefore incapable of self-government and political autonomy. The struggle for freedom was, thus, also a search for national history.

Universities should recognise how they have helped propagate this narrative. Introduction of Western academic history as a university discipline in the late 19th century coincided with the age of high imperialism. Its emphasis on “great men” encapsulated the same spirit that celebrated colonial administrators. The importance of “objectivity” in historical research, characterised by a steadfast adherence to data gathered from official textual archives, gave expression to this approach.

Western influence on Indian history did not end with independence since Europe remains the primary point of reference in scholarship. In addition, the marginalisation of empire in school and university curricula is exacerbated in educational institutions outside India by the limited attention paid to South Asian history, tough competition from more conventional histories, and mythologisations of Europe and the US.

Students from postcolonial migrant backgrounds in the US and Europe have also struggled to locate themselves within curricula. This alienation exacerbates the sense of colonial displacement brought about by the prevalence in UK universities of white, middle-class privilege, often derived from prior politico-cultural and economic investment in imperialism.

So what can be done to change the narrative? Although historians are increasingly including empire in school and university curricula, we also need a re-evaluation of what historical evidence is. With written records understood as a hallmark of historicity, any perceived absence (or neglect) of textual documentation placed many societies and nations beyond the scholarly pale. A reconsideration of this stance leads us to rethink not only racial hierarchies but also those of class and gender; writing was (and, to some extent, still is) a social privilege, indicative of cultural and symbolic capital.

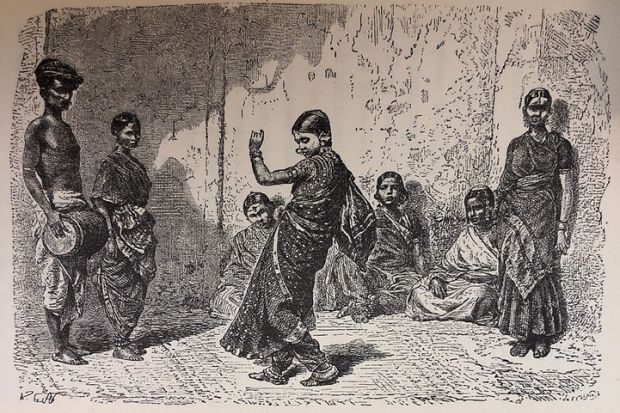

People in the past preserved their everyday experiences and expressed their aspirations in other formats, particularly images. Despite artificial distinctions between so-called high and low art, the symbolism and visual formulae of images are universally accessible.

Including images in the teaching of India’s colonial history would not be an exercise in experiential learning, nor just a means to overcome the boredom associated with written materials. It would align with New Imperial History’s emphasis on transcending the written word to trace colonised peoples’ agency. Images document how the British achieved political authority, responded to Indian life and nature, and imagined themselves as an imperial power. Indians also produced visual arts that gave meaning to their existence under colonial domination, fuelling resistance to it. Images were thus not simply a celebration of the British Empire, but a reflection of its tensions and anxieties.

When teaching the history of colonial India, we must also remember that imagery was a staple of imperialistic propaganda in Victorian Britain. Schoolchildren and university graduates viewed maps doused in pink, images based on imperial policymaking and picturesque scenes in textbooks. Moreover, empire was brought home through circuses, freak shows, zoos, exhibitions and even board games. The inclusion of images in historical curricula is therefore the resuscitation of a long-established practice, which must be made responsive to present concerns.

Teaching with images demands acknowledgement that certain representations can be graphic and potentially unsettling for those who may see their forebears in them, whether as denigrated victims or perpetrators of imperial violence. But, as educators, it is our responsibility to interrogate the problematic and differential attitudes meant to sustain the British regime.

Discussing images’ context and messages is a powerful way to navigate the culture and politics of discrimination that is central to our shared imperial inheritance. It would encourage both critique of the colonial past and address instances of current everyday racism.

Apurba Chatterjee is a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow in humanities and social science at the University of Reading.

后记

Print headline: Evidence goes beyond words