Recently, one of my students requested the use of a personal “memory aid” – a pre-written notecard – in an exam. According to my institution, the accommodation was “required for equal access”, even though a memory aid obviously undermined the evaluation’s major purpose: to test the student’s ability to recall class content. I had to grade her exam like everyone else’s, as if she hadn’t used a memory aid. Her grade, therefore, was a lie.

Nor is this an isolated case. Faculty are increasingly being asked to provide accommodations, which also include note-taking assistance, class recordings, essay deadline extensions, extra time on exams and private testing locations. Many colleagues privately express disapproval, but we are required to provide them for all documented disabilities (including “mental impairments”) because, ostensibly, this is what the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 requires.

Specifically, the act requires places of “public accommodation”, including post-secondary institutions, to provide “reasonable accommodations” to people with disabilities unless they “can demonstrate that making such modifications would fundamentally alter the nature of [any] goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations” they provide.

One student complained to me about my evaluation of his writing. If he had previously studied composition, like some of his peers, he would have performed better, he said: “How is it fair for me to be penalised for something beyond my control?” The answer is that universities should not strive for fairness – in this student’s sense of the word – because doing so fundamentally undermines a primary good they provide: namely, credentialing.

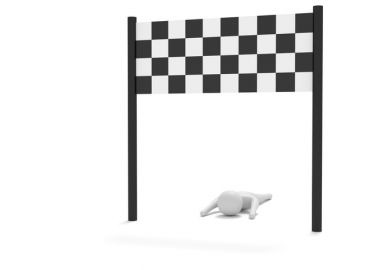

In a 2017 article in the Canadian newspaper National Post, Bruce Pardy, professor of law at Queen’s University, argued that accommodations such as “extra time for mental disabilities” are “as unfair to other students as a head start would be to other runners” because the purpose of exams is to discriminate among students based on “how well they can think, learn, analyze, remember, communicate, plan, prepare, organize, focus and perform under pressure. Discrimination is one of the purposes of the exam.”

My student’s sense of fairness is different from Pardy’s. It suggests that students should be evaluated based on how they would have performed if they didn’t have disabilities – which, after all, they cannot control. As the editorial board of The Queen’s Journal, a student-run newspaper at Queen’s University, put it in response to Pardy: “Rather than guaranteeing a better grade, [accommodations] give students the chance to achieve a result that reflects what they can really do with their academic ability.”

But nearly everyone agrees that there are some disabilities that should not – or could not – be accommodated. Examples include diseases that severely impair cognitive development, memory or ability to participate in a normal classroom environment. Moreover, many people without disabilities are still academically disadvantaged by other factors they cannot control. Should we accommodate those whose intelligence is negatively influenced by their genetics, for instance? Or those who were raised in poor households with few books, or who are addicted to video games, or who have headaches on exam day?

Kurt Vonnegut’s 1961 short story Harrison Bergeron portrays a society so obsessed with fairness that it seeks to eliminate all environmental and genetic factors that affect performance. The intelligent wear “mental handicap radios” that sonically interrupt their thoughts; the beautiful are masked; the athletic are yoked with weights and imprisoned for removing them. A news anchor reporting an emergency has a speech impediment so severe that he cannot vocalise.

Clearly, this is ridiculous. At a certain point, we all have to accept that life is just irremediably unfair. To be generally useful, performance evaluations must provide comparative assessment of ability. This requires comparative fairness, the measuring of like against like, which is why evaluations must be conducted under the same conditions – under which some people will perform better than others because of factors they could not control.

For instance, to determine which scientist should be entrusted with important research, we need to know who performs better (and worse) than peers under real-world conditions, which include distractions, time pressure and team-working. The same goes for surgeons, lawyers, electricians, civil engineers and a whole host of other professions in which underperformance can have dire consequences for patients or clients. A university’s credentialing, involving grading, degree conferral and its own reputation, is vital for assessing relative merit.

In operator training for planes and vehicles, even strength of eyesight is relevant, so accommodating poor eyesight by giving extra time to identify potential hazards would provide a false idea of relative ability, for instance, to fly a plane safely. In typical university disciplines, however, poor eyesight is irrelevant to real-world performance. Consequently, eyesight accommodations, such as enlarged text, are acceptable.

Another way of putting the point is that any accommodation that would advantage an arbitrary student should be avoided. Extra time in exams is an obvious example. Intellectual agility, speed of thought and execution, is generally relevant to real-world competence, so any accommodation that gives a false impression of student agility is illegitimate.

Universities that offer such accommodations, however well-intentioned, compromise their credentialing ability. They flout the assumption that grades represent like-for-like comparisons among peers. They deceptively imply that all students within a particular grade boundary can perform equally well in the real world. They falsely say that all degree holders are competent.

These are lies that we need to stop telling.

Justin Noia is a visiting assistant professor at Providence College, Rhode Island.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?