Most coverage of Labour MP David Lammy’s recent release of Oxbridge admissions data presented the continued dominance of privileged students as evidence that both ancient universities’ admissions processes remain deeply unjust. Lammy himself suggested that there may be a “systematic bias” against black and socio-economically disadvantaged applicants, while a cascade of more aggressive accusations of institutional racism and elitism echoed around social media.

Having been an undergraduate admissions tutor at the University of Oxford for five years, I was depressed by both the data and the difficulty that Lammy had in acquiring it. His efforts provide a much-needed impetus for re-examination of admissions procedures.

But his diagnosis is too simple. Evidence of disparities between the profiles of students offered places and the national population does not, by itself, tell us anything about the actual source of those disparities. They might reflect biased processes, but they could also reflect inequalities that long pre-date university application. This has long been the argument of the universities themselves, and while some suggest that Oxbridge is simply in denial about its internal bias, the statistics largely support the universities’ case.

We can admit only those who actually apply, so one has to start by comparing offer statistics with application statistics. But Lammy’s data do not list the ethnic breakdown of applicants. Hence, they cannot tell us whether the lower numbers of black students entering Oxford (1.5 per cent of all admissions, compared with the 3 per cent of the overall UK population that is black) reflects institutional bias, as opposed to black students’ relative reluctance to apply or lower A-level attainment. Wider evidence suggests, though, that the deep educational disadvantages faced by black British students at school level are crucial. While 13 per cent of UK students obtain three As or better at A level, only 5 per cent of black students do so, and such differences necessarily impact access to top universities.

Lammy’s data contain clearer information on the regional and class profile of Oxbridge applicants, but much of it also supports the universities’ case. As Patrick Scott pointed out in The Daily Telegraph, for example, the fact that no one from Middlesbrough was accepted by Oxford in 2015 looks less shocking when you realise that there were only three applications from that underprivileged northern city.

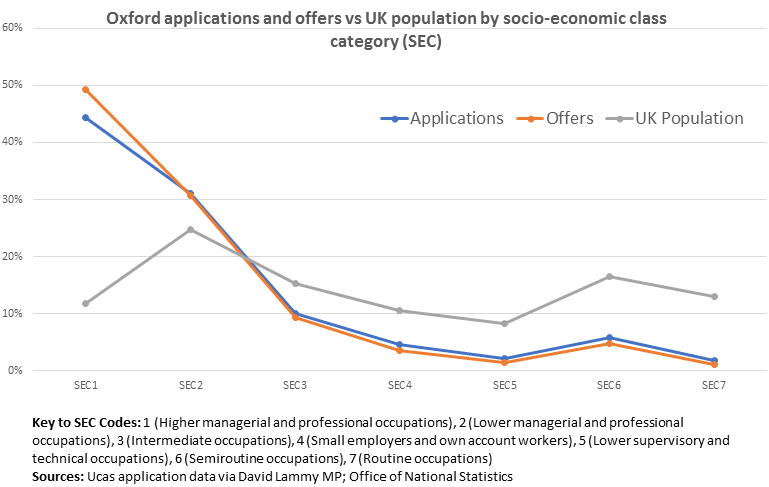

As for class, Lammy’s data show that the distribution of Oxford offers almost exactly matches the class distribution of applicants. The correlation isn’t perfect: students whose parents have higher managerial and professional jobs are slightly over-represented, receiving 49 per cent of offers while comprising 44 per cent of applicants. This is a cause for real concern but could, again, mainly reflect the pre-existing educational advantages enjoyed by such students. Either way, its effect is dwarfed by the differences between the applicant pool and the general population.

Since becoming involved in Oxford admissions, I have generally been impressed by my colleagues’ drive for fairness. Most are deeply frustrated with the levels of inequality in access and actively try to address dangers of implicit bias. Several recent developments are, moreover, major steps forward in addressing disadvantage, especially the greater use of contextual data in admissions and the introduction of foundation-year courses such as those being introduced at Oxford’s Lady Margaret Hall. But we do need to do more. Centralised intervention to guard against bias could help, and Oxford and Cambridge need to intensify efforts to tackle their pervasive reputation – only worsened by recent coverage – for welcoming only the privileged. Both universities should also increase the weight attached to individual-level contextual data, as advocated last week in a report by the Sutton Trust.

But as one of the authors of that report, Claire Crawford of the University of Warwick, observes: “The relatively small numbers of students from disadvantaged backgrounds who secure the highest A-level grades remains the biggest barrier to widening access to elite institutions.” Even if the Oxbridge admissions systems were literally perfect, they could never undo the vast educational inequalities that UK students face over their first 18 years. Greater efforts to improve access are needed, but dramatic progress will prove impossible without fundamental changes to the structure of British primary and secondary education.

Jonathan Leader Maynard is a lecturer in international relations at New College, Oxford.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: To be fair, this is beyond us

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?