A widely held belief in Canada, as in many countries, is that expanding access to tertiary education is integral to improving national productivity. It also plays into the Canadian sense of equality of opportunity and the just society.

In addition, Canada is not alone in beginning to experience a decreasing labour force participation rate as the baby boomer generation enters retirement. Even the country’s large immigration flows are not sufficient to compensate for the labour force shrinkage. This puts additional pressure on productivity; across the 20 largest members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, this would need to increase at an average of 0.4 per cent per year to offset the loss of gross domestic product per capita.

The importance of an increasingly skilled workforce is one source of interest in higher education access rates. But declining numbers of people moving into the standard age range for higher study is threatening to force some institutions to downsize or even close entirely. This can cause particular pressures in rural areas and disadvantaged regions, where higher education institutions often represent an important social, economic and cultural force. Furthermore, apart from their teaching function, tertiary level institutions also typically play a critical role in a nation’s performance with respect to research and development.

Standard models of human capital (held dear by most economists) posit that individuals make rational choices about higher education, based on the information available to them, aimed at maximising their lifetime well-being. Their decisions supposedly take in their intellectual ability, other choice factors such as personal tastes, and the costs and benefits of these choices. In practice, this model has been associated with a narrow policy focus on costs – especially tuition, and student financial aid.

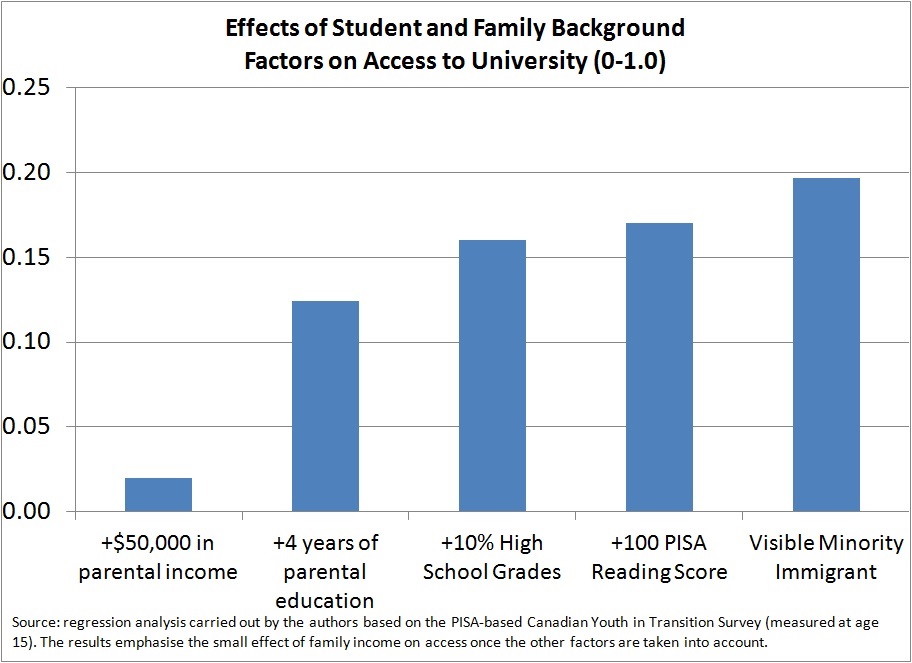

However, there is a mounting body of empirical evidence showing that cultural influences represent the most important determinants of access in Canada. These include parental education, reading habits and parental and community aspirations – particularly, the pro-education values imported by immigrant families, whose access rates generally far exceed those of non-immigrant youth.

At their current levels, financial issues are not the central barriers to increased access. That is not to say that tuition should be increased, or financial aid decreased. But it is to say that cultural factors need to be reflected in access policy, too. And, importantly, related initiatives need to begin in childhood – certainly earlier than high school graduation, at which period existing financially focused policies are targeted.

The policy challenge is to both increase higher education access across the board and level the playing field for youth from different cultural backgrounds. How can we, for example, reach out to children who do not have accurate information about higher education’s benefits and costs, or who fail to grasp the importance of academic preparation for it?

Such an approach will allow us to implement policies that have the potential to make much greater differences than traditional money-based initiatives do. But further research is needed on how to best execute it – including the implementation and evaluation of trial programmes.

Perhaps, for example, youth from communities with low access rates could be taken on visits to college and university campuses – possibly from as early as primary school. Alternatively, youth from such communities who are currently in higher education could be invited back to their secondary schools to speak of their experiences. They could even be put into mentoring relationships with students from low-participation secondary schools.

Another idea is that senior secondary school students could be given in-school assistance with application forms for university admission and financial aid. Academic or social support of different types after matriculation may also play a key role, although the Canadian evidence suggests that first-generation students generally perform about as well as others once admitted.

Whatever the merits of these approaches, it is clear that cultural factors must be addressed if Canada is to develop the highly educated workforce it needs to have a highly productive economy and support its economic and social goals.

Ross Finnie is professor and director of the Education Policy Research Initiative (EPRI) at the University of Ottawa. Arthur Sweetman is professor at McMaster University and associate director of the EPRI, and Richard E. Mueller is professor at the University of Lethbridge and associate director of the EPRI.

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?