Touching down at Santarém airport in northern Brazil in November 2015, Jos Barlow braced for the powerful tropical heat of the Amazon once again. When the plane doors opened, however, it was not the 35ºC temperatures and 95 per cent humidity that he noticed.

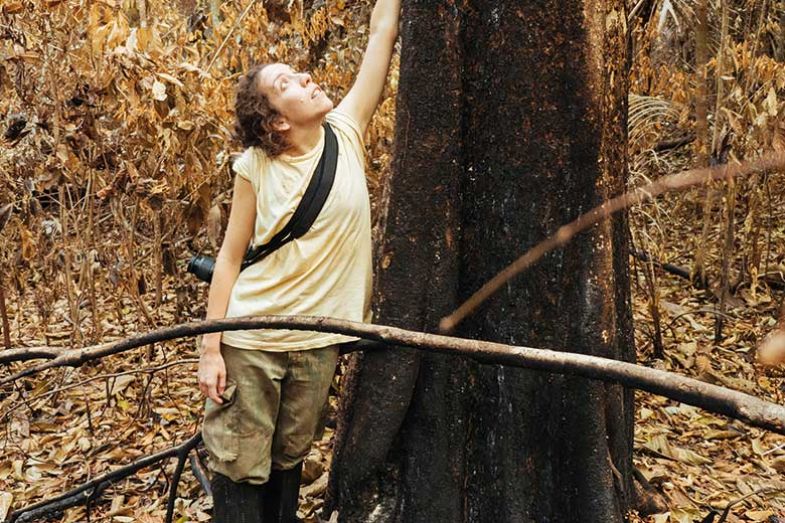

“As soon as I stepped off the plane, I could feel the acrid smoke burning my eyes and my throat,” explains Barlow, professor of conservation science at Lancaster University, who has been visiting the Amazon at least twice a year since 1998. As part of a UK-Brazil research project, he and his fellow researchers had travelled to the city a few hundred kilometres inland from the Amazon delta as part of a project to examine tropical forests’ capacity to regenerate after wildfires or logging activity.

But the flames that he encountered were on a different scale from those previously seen in the world’s largest tropical forest. Almost 6,000 sq km of the Santarém region were burned during 2015 as fires lit by legal loggers to clear the undergrowth from logged areas ahead of replanting blazed out of control. To put that into context, 6,000 sq km is roughly four times the area of California destroyed last year by the headline-grabbing Mendocino Complex Fire, the largest wildfire in California’s history.

The fires led 12 Amazonian cities to declare a state of emergency in October 2015, mainly because of the chronic respiratory problems caused by inhabitants inhaling smoke for months. In November alone, the Brazilian Amazon was scorched by nearly 19,000 fires, satellite data showed.

“We knew there was an El Niño drought that year, but the extent of the wildfires was really shocking,” says Barlow, who has also studied tropical forest biodiversity in Africa and Central America. “The whole region was shrouded in smoke, so driving became quite hazardous, with visibility down to metres in some cases.” Logging practices that strip the forest of its density and foliage, coupled with extreme temperatures, had “turned a fire-free ecosystem into one that was much more flammable”.

“Rainforests are normally very humid and dense, but this type of logging opens them up to more light and winds – they become a bit like Swiss cheese,” explains Erika Berenguer, senior research associate at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute and a visiting researcher at Lancaster, who accompanied Barlow on the 2015 expedition. “When fire comes, the forest cannot stop it, and it just burns for thousands of hectares,” she adds. “This is not like a forest in the US or Australia that renews thanks to fires – it doesn’t normally burn.”

The constant smoke made working conditions unpleasant and uncomfortable for the researchers as they analysed the ecology of 20 plots of 3,000 sq km scattered across the Santarém area, admits Berenguer, a Rio-born Brazilian who did her PhD at Lancaster. The sun was red when it was even visible at all, and the constant barbecue-like smell permeated their clothes and hair. But the most unsettling thing, she says, was the near silence. “These forests are normally very noisy places – you constantly hear frogs, birds and other animals – so it was strange, even eerie, to hear nothing at all,” she explains. “That’s what strikes you the most.”

Visiting fire-damaged sites that she had monitored over the years was also emotionally tough, continues Berenguer. “As academics, when we talk about the effects of logging and destruction of nature, it is affecting but it’s still something you’re distant from. Then you step into the aftermath of fire and see trees you know and visited many times that have gone – areas you love have become awful places. We’re often looking at the effects on ecology of something that happened two decades earlier, but this wasn’t the case when the fires were still burning. Seeing the forest destroyed and being unable to stop it is hard.”

Unlike the Californian wildfires that ripped through the US state between June and November last year, causing 104 deaths, the Amazonian fires never threatened to overwhelm those working near them. “The flames are only about 30cm high and don’t move very quickly, so you wouldn’t struggle to escape from them,” says Barlow.

That said, trekking deep into the rainforest to examine remote sites as fires continue to smoulder can be a risky undertaking, he adds. “When half the mature trees have died, the forest becomes very hazardous – you often hear trees crashing down around you,” he explains. Falling branches in fire-damaged areas can also pose a problem. “When you hear cracks above in the branches, you just have to get out of there as fast as you can.”

Moreover, the damage done by loggers to the Amazonian forest means that the risk of fire is now much greater than it was, with the potential for fires to spread much faster than the 2015 fire did, Barlow believes. “When you have very degraded forests, they become dominated by bamboo and grass,” he explains, creating tinderbox conditions.

Snake bites are another major danger for those heading into the Amazon. The region has 17 types of deadly snakes, and “every researcher knows someone who had a fatal or near-fatal accident involving snake bites,” Barlow says. “You’ll also hear from those giving you lifts into the forest that they’ve been bitten, so it’s important to wear boots and snake guards [around the lower legs].”

Almost any injury, snake-related or otherwise, is a potential hazard when it is two hours’ walk to the nearest road, adds Barlow. “But things have got a bit easier with satellite phones. You can call in small planes in an emergency – but the emphasis is still on taking precautions.”

On that score, however, he admits that he has not always been as attentive to risk as he should have been. “When I was a PhD student and living with the local community, I would often just head into the forest wearing flip-flops, as it was what everyone around you did,” he recalls. That attitude changed for ever when he later discovered that someone he worked with during this time had subsequently died from a snake bite.

Brazil’s horrifying murder rates are another factor that cannot be ignored by those venturing into some of the country’s less policed areas, adds Barlow. Almost 60,000 people were murdered in Brazil in 2015 – about 164 a day in a country of 200 million people – with violence particularly bad in the northern cities.

“It’s definitely got worse in the Amazon in recent years – the Amazonian state capitals are among the most violent cities in the world,” Barlow says. The murder of British kayaker Emma Kelty while travelling solo on the Amazon in September 2017 underlined the threats to those foraying deep into the Amazon: “The water is pretty lawless when you get away from the bigger cities.”

But none of this, Barlow says, has led to any shift in either his or his institution’s assessment of the risks involved. “Research is very different from exploration and adventure, as most activities require working in small groups,” he says, as opposed to travelling alone. “We also ensure that we work closely with local people, who understand many of the local risks much better than we can.”

But while the risks to researchers in the Amazon may remain relatively low, the peril facing the rainforest itself is perceived to have escalated dramatically with the recent election of Jair Bolsonaro as Brazil’s president. The far-right nationalist, an admirer of Donald Trump, has vowed to put production in the Amazon ahead of protection by tearing up environmental laws, weakening enforcement agencies and giving the green light for more roads in the tropical rainforests. In several speeches, he has also vowed to end the “fine industry” run by Brazil’s environmental agencies – giving the nod to illegal loggers that they will not face criminal action, opponents claim.

“The change in government will mean a relaxation of environmental laws and more deforestation,” reflects Berenguer. And this comes at a time when tougher fire management is imperative, with the number of extreme droughts in the Amazon likely to triple by 2100, according to a 2015 report by US researchers, creating more fire-friendly conditions. Logging firms, she believes, should be forced to build firebreaks: 3m-wide corridors hand-cleared of all vegetation so that fires can’t cross them.

“Anyone can build a firebreak, but it is really hard work – I’ve done it myself,” Berenguer says. This laboriousness, plus the lack of financial reward for doing so, means that loggers rarely build them. But any repeat of the mass fires of 2015 will have devastating consequences for both human health and the natural environment, she warns.

Fires in the south Asian peatland forests in 2015 emitted more carbon in just a few weeks than the entire German economy did that year, according to an article that Berenguer and Barlow co-wrote at the height of the Amazon fires. And each hectare – roughly the size of a football pitch – that burns in the Amazon emits roughly the same amount of carbon as would a new car driven around the world 61 times.

Meanwhile, cases of breathing problems in Brazil more than trebled during the fires of 2015. “It was mainly children and elderly people affected,” Berenguer reflects. “Being killed by fire was not our concern – the major risk is the respiratory problems affecting not so much researchers as those who cannot leave once a field study is complete.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?