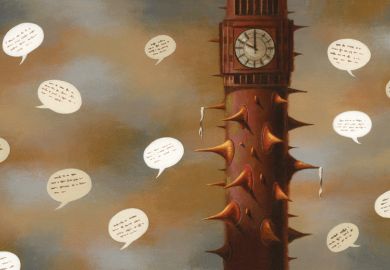

Creating a single giant UK database for researchers and technology firms to mine for potential insights will be risky, expensive and unlikely to deliver breakthrough discoveries, leading scholars have warned about Labour’s plans for a national data library.

In the most detailed suggestions of how the UK government’s plans for a vast central archive of public data might be achieved, some of the country’s top data experts have expressed grave concerns that the project would mean the construction of a massive standalone data platform, operated by a “huge monolithic delivery organisation”, which researchers or algorithms could trawl widely for potential insights.

Few details have been provided about how Labour will deliver its manifesto commitment for science, yet prime minister Keir Starmer said the library will open up NHS health records – including scans, biodata and anonymised patient data – to big tech companies to help them train artificial intelligence models.

Responding to a Wellcome Trust and Economic and Social Research Council call for papers into the proposed library, Ben Goldacre, director of the University of Oxford’s Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, cautions that the “default design principle from all previous government data projects has been to try to put all the data about all citizens in one big box, then let analysts log in to use it there, in whatever way they wish”.

“This makes superficial sense: ‘My team needs tax [and] health [and] schools data in one analysis, so we need all the data in one machine.’ In reality this aggregation is unnecessary: it also creates huge problems for privacy, and obstructs delivery,” explains Goldacre, a public science figure who now heads a 60-strong team of researchers and data scientists exploring GP data.

In a submission co-authored with Bennett Institute software and engineering leads Seb Bacon and Pete Stokes, Goldacre advises the government against creating “one single huge database”, arguing these “data lakes” are “terrible for privacy”, “bad for transparency and audit” and “bad for data management”.

They also tend to “create conflicts between institutions” given that a team which might have “worked for years to create a complex national database on every citizen’s tax/school/pension/etc [will not] want to hand all ‘their’ data to a national data lake”.

“They worry about losing control or sight of the uses, that users will misunderstand the…data they love, or do misleading analyses; they worry that bad analyses will affect the…team’s reputation; that others will take credit for [their] work; or get privileged access to do analyses first,” the trio warn.

Instead, Goldacre urges the creation of a “federated model” for the national data library in which “raw data in each data centre or department stays put in that source data centre”, and users follow a “take only what you need” approach rather than extracting all data.

Using this “network of standalone services, stitched together into a platform”, the library should also concentrate on improving “top three datasets [within each domain] that researchers actually want” rather than seeking to create “omnipotent systems”.

“Researchers should use the Scrapheap Challenge approach too,” they add in the submission, explaining that researchers should “reuse what exists today” in an innovative way rather than complaining about insufficient databases.

Other submissions, including one from the UK Research and Innovation-funded Dare Project set up in 2021 to improve national data use, also back a federated structure, suggesting a “membership organisation” involving “a community of operators around a single set of technologies”.

“To build everything from scratch would be expensive and risky, and result in an immature product in an environment requiring mature security,” it says.

However, others caution against progressing the project until the problems it will solve are clearly defined and it is known whether they could be solved more easily in other ways.

A submission from Icebreaker One, a UK non-profit organisation focused on data sharing, highlights a former government adviser’s advice: “Don’t build a new thing unless you definitely, absolutely must.”

Instead, the government should acknowledge the “UK’s research data ecosystem is crowded” and consider whether the aims of the national data library could be solved by drawing on existing data infrastructure.

The library “could easily be a lame duck given there are already many places where researchers can already find public sector data available for research”, it says.

Noting that the UK’s long-standing failure to bring together data from multiple organisations – including Whitehall departments, NHS trusts and public bodies, is largely a governance problem, it warns the national data library may be a “technical solution to a systemic challenge”.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?