News that the next round of England’s teaching excellence framework will use the Department for Education’s new dataset on graduate earnings by university and course is likely to raise concerns for some in the sector.

Countless factors affect the Longitudinal Education Outcomes data beyond the institution attended, such as prior school attainment.

Many warn that unless the data are properly benchmarked for these factors – by comparing a university’s performance on graduate employment with what might be expected for its location and mix of students – there will be fears that some institutions could be unfairly penalised in the TEF.

A key example is how graduate salaries vary by region.

The LEO data do not include information on exactly where graduates worked after leaving university, but comparing the average salaries earned with the location of the university attended gives a flavour of the kind of differences that occur.

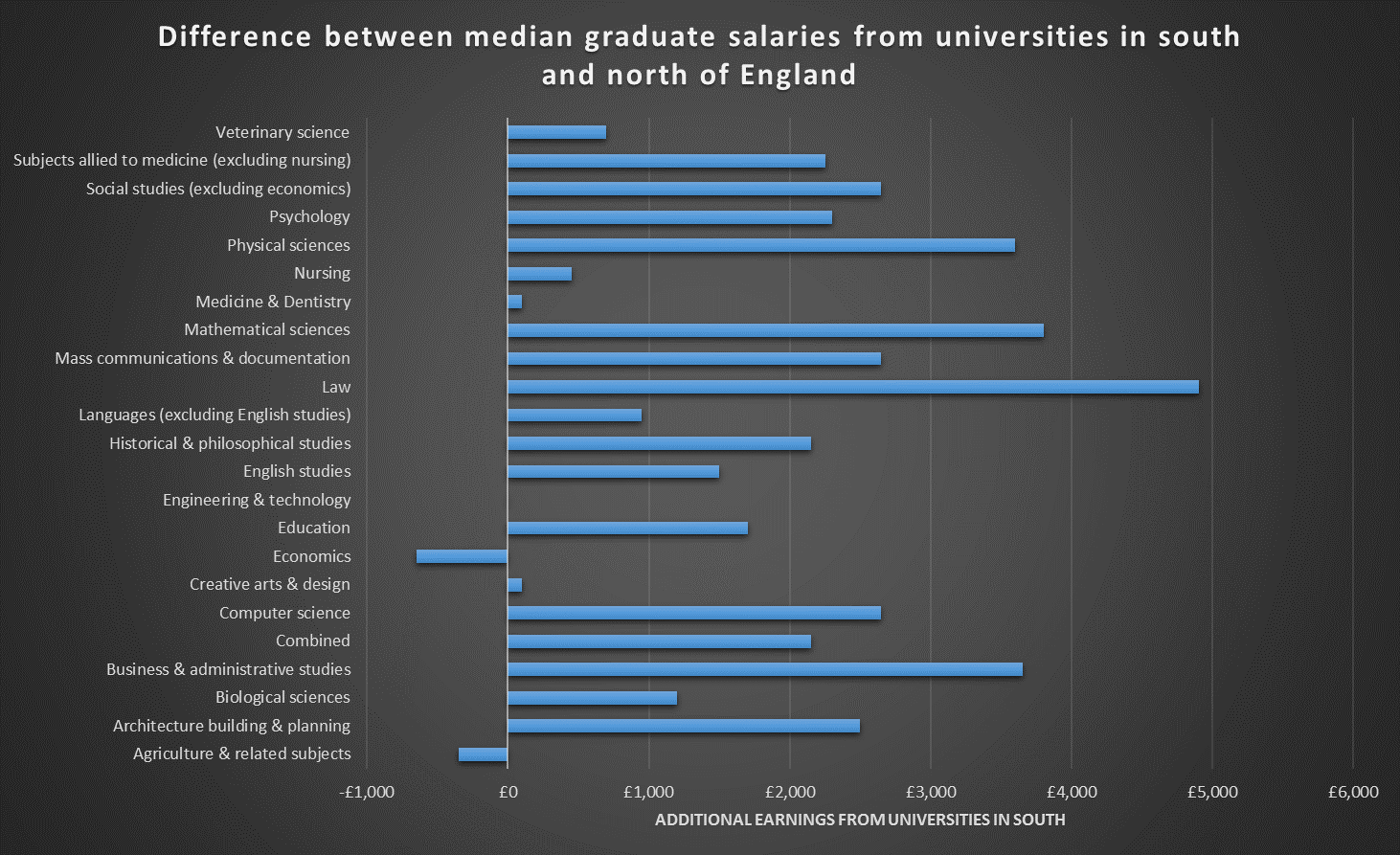

In particular, comparing universities from the North and the South of England (defined by a commonly used approach of drawing a line from the Severn estuary near Bristol to the Wash, at the border of Lincolnshire and Norfolk) shows a clear divide in what graduates can expect to earn.

In only two subjects can graduates of northern English universities expect to earn more, on average, than those who go to universities in the South. And according to the data, it is law and maths degrees that have the biggest “North-South divide” in salaries, as can be seen from the graph below.

For law, the difference in median salary after five years (for men and women) is just under £5,000, while for the mathematical sciences it is almost £4,000.

The only subjects where graduates of northern universities earn more than those who attended institutions in the South are agriculture and economics. But even the somewhat surprising difference for economics has an explanation: a handful of less-selective universities in London bring down the average for southern institutions.

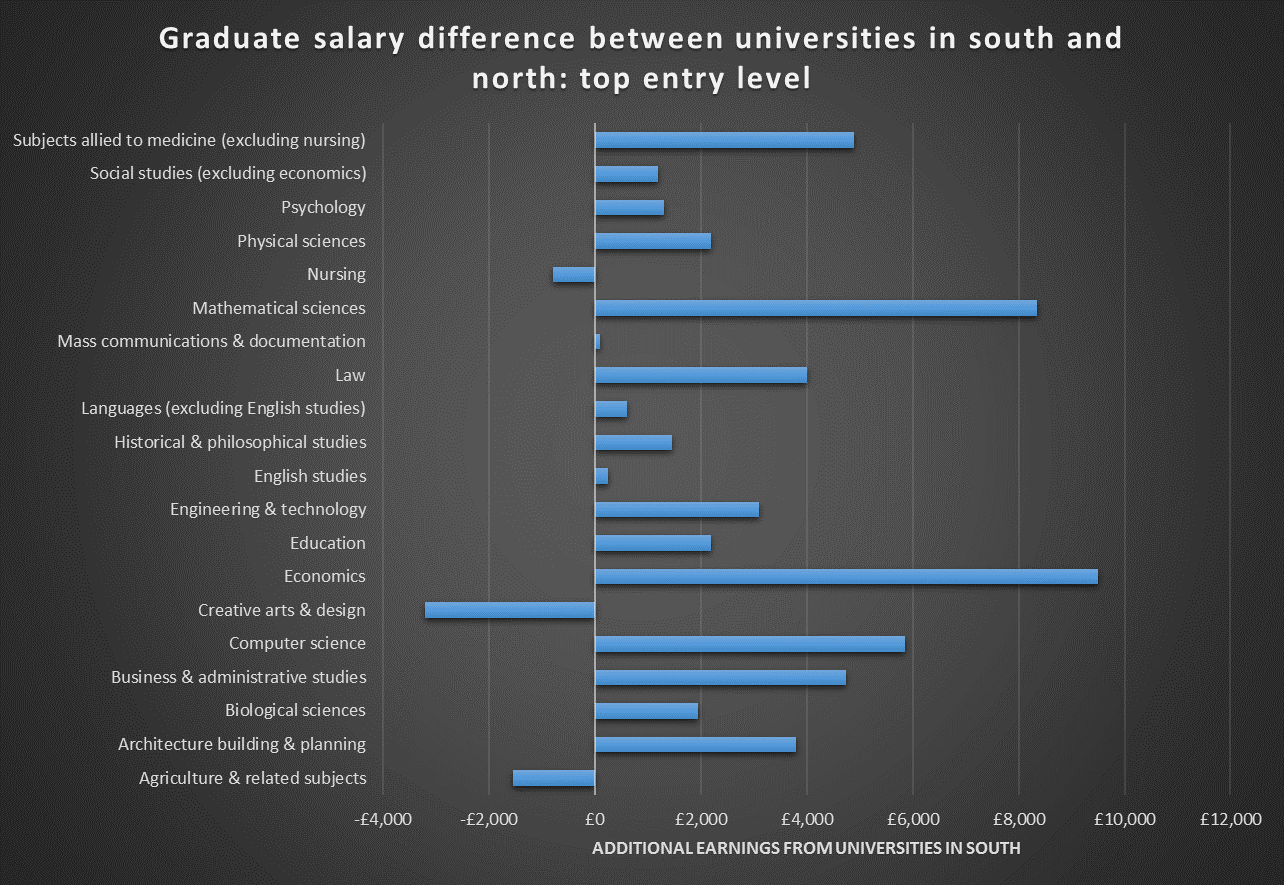

Some of the North-South graduate salary variations become even more pronounced when comparing universities with similar entry standards for students.

For those that admitted students with the highest A-level grades, for instance, economics courses in the South of England actually produce graduates who go on to earn almost £10,000 more on average after five years.

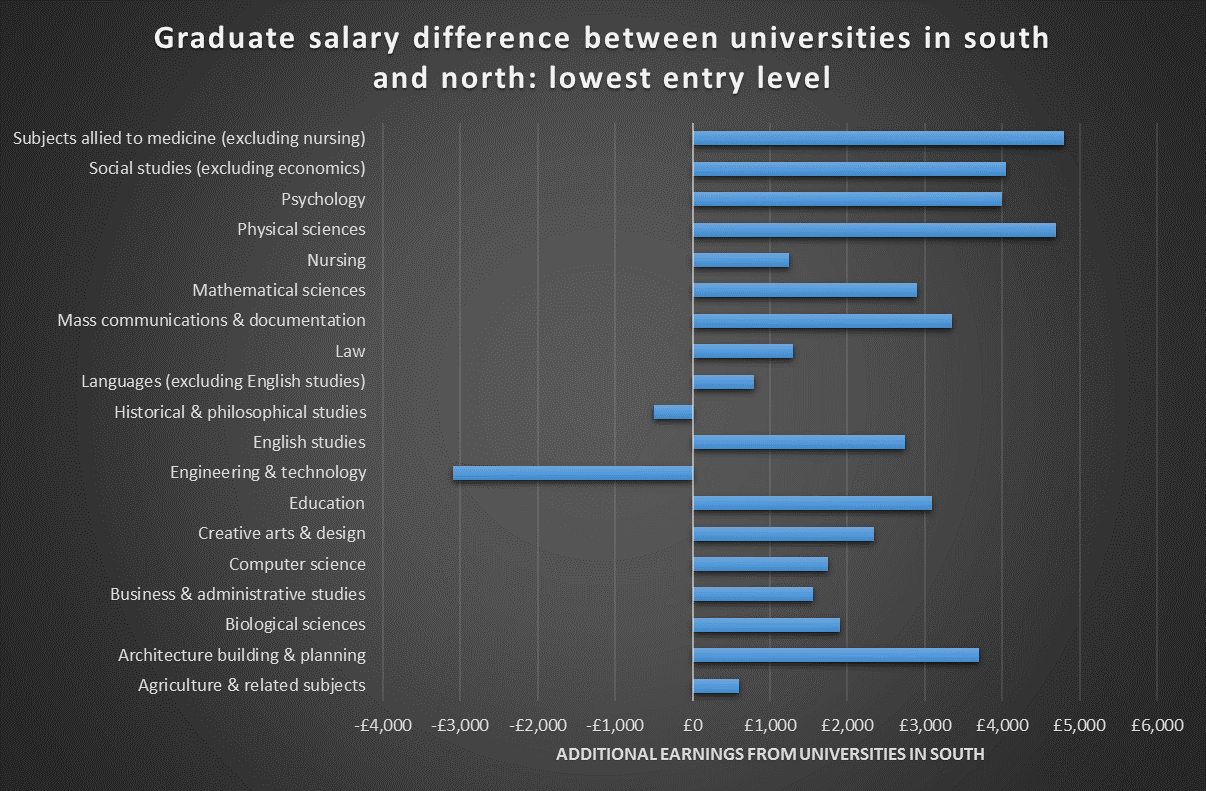

For universities that have lower entry standards, the salary differences are smaller but still exist for the vast majority of courses.

Jack Britton, a senior research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, who is part of a research team that aims to analyse the LEO data against a range of contextual factors, said that if the TEF used graduate earnings data, he was “pretty certain” that it would try to benchmark them for regional salary variations.

However, because LEO had data only on the university attended, and not graduates’ work locations, benchmarking could benefit institutions in areas outside London where local salaries were lower, but whose graduates typically worked in the capital.

“There will definitely be winners and losers from that. If you think about…universities [such as] Warwick or Oxbridge, a lot of their graduates will end up in London but they would not be getting that London adjustment in the same way that, say, Imperial [College London] or LSE would,” he said.

These problems also demonstrated how complex it was trying to benchmark the TEF for different factors without penalising some institutions, Dr Britton said.

Maddalaine Ansell, chief executive of the University Alliance, said that while LEO was an “excellent tool” for looking at graduate employment outcomes, “there are many other, stronger, factors in play like regional variation in economic conditions when thinking about how to use it to measure university performance”.

And Pam Tatlow, chief executive of the MillionPlus association of modern universities, warned that the LEO data’s correlations with other factors demonstrated why it was “rather dubious” to use them to measure teaching quality.

simon.baker@timeshighereducation.com

This is an updated version of an article first posted online on 18 July.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Good degrees, or just good locations?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?