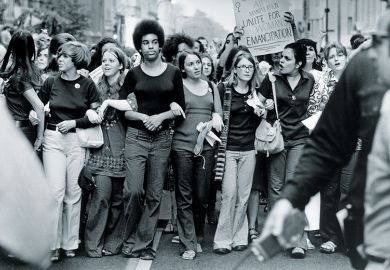

Female economists collaborate with a more limited network of colleagues than their male counterparts, and this may be holding back their research careers, a new study suggests.

A paper set to be presented at a conference at the University of Kent on 27 June asks why the output of the average male economist remains 54 per cent higher than their typical female counterpart. This gap has remained persistent even as women’s share of the profession has increased from 8 per cent in the early 1970s to 29 per cent at the end of the last decade.

Examining authorship data for more than 1,600 economics articles published between 1970 and 2011, three UK-based researchers found that both women and men were more likely to collaborate with authors of the same gender. Although men made up 72 per cent of authors during this period, 81 per cent of their collaborations took place with other men; and while women accounted for 27 per cent of the population, 33 per cent of their co-authorship was with other women.

Female economists tended to have fewer distinct co-authors than men, to collaborate more with the same co-authors, and to operate within more tightly “clustered” co-authorship circles.

They were also more likely to collaborate with more senior colleagues, at every stage of their career. Although this may improve the project’s chances of success, this means that they may receive less credit from the partnership.

Lorenzo Ductor, senior lecturer in economics at Middlesex University, Sanjeev Goyal, professor of economics at the University of Cambridge, and Anja Prummer, lecturer in economics at Queen Mary University of London, suggest that these results were consistent with the view that “women make less risky choices with regard to collaboration”.

In turn, taking fewer risks and partnering within narrower groups may contribute to women’s lower research output, their paper suggests.

The trio say that women may take fewer risks because they face a “more challenging and possibly more uncertain” academic career than men; previous studies have shown that their work spends longer in peer review, that they receive lower teaching evaluations, and that they get less credit for work done jointly with co-authors.

Dr Prummer told Times Higher Education that female economists faced a “hostile environment”.

“If there is systematic discrimination in economics, then women may choose collaborations to insure themselves against adverse outcomes, choosing to stick to a close-knit circle of collaborators,” she said.

“It may also be that women simply perceive the environment in economics to be more hostile, which can affect how much risk they are willing to take and how willing they are to embark on new projects with other economists they do not know well.”

Creating a fairer working environment in which women are made to feel “that economics is also a female profession” would help to improve the gender balance in research output, Dr Prummer said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login