“You don’t make a career being a Syria specialist.”

No statement better captures the attitudes of American social scientists towards international inquiry than this one from, of all people, a director of Middle East studies at a major US university. He isn’t the only one who feels that way.

For more than a decade, our research team conducted dozens of interviews with faculty and administrators at 12 leading US universities. We wanted to know why so few scholars in economics, political science and sociology had bothered to study the Middle East, but also other world regions beyond North America and Europe. What we learned took us deep into the heart of the US academy.

Senior faculty in elite social science departments consistently steered their doctoral students towards US-specific problems. One economics professor told us that his colleagues discouraged foreign language learning because students “wouldn’t get any credit for it in the economics marketplace”. From sociologists, we heard that preoccupation with American society drives a job market that is “ethnocentric and focused on the United States”. And from political scientists, we heard that regional specialisation has lower status than deftness in sophisticated quantitative methods.

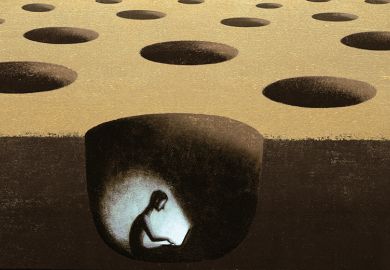

So why are American social scientists such reluctant internationalists? This is not simply a story of “America First” nationalism; it begins with an organisational structure that houses each academic discipline in its own stand-alone department. With faculty siloed in this way, research primarily geared towards specialists in one’s own discipline gets first priority. Other audiences are thought of as extras.

Graduate training also plays its part. Young recruits to each discipline are encouraged to direct their research to problems defined in disciplinary terms. Theory and method are prized above contextual questions or particular problems. Journal editors and faculty hiring committees alike want to see that the methods and theories employed are applicable in multiple regions, so as to ensure the biggest and boldest contributions to their fields. Becoming too rooted in research on one place – unless it is the US – puts scholars at risk of derision from colleagues. Many people who we spoke to referred to area studies scholarship as biased, atheoretical and passé.

The limited availability of quantitative data describing many parts of the world is an additional and powerful disincentive to regional inquiry. As the social sciences get “teched up” and rely more heavily on sophisticated mathematics to find order in large-scale numerical datasets, countries in which data systems are weak, heavily restricted or non-existent are rendered invisible to investigators.

Of course, not all US social scientists are entirely US-focused. We heard from academics across the country who valued contextual expertise and who were themselves expert scholars of particular places.

But time and again, faculty told us that scholarship addressing North American (and, to a lesser extent, European) topics was the best bet for successful careers.

Search our database of jobs in North America

But when academics won’t make careers out of being Syria specialists, others will. The space of opinion on global affairs is increasingly filled by parties who specifically intend to direct government policy and popular wisdom in partisan ways. And because the cost of entry into public discourse has been reduced almost to zero by digital media, wildly divergent versions of reality can vie for global audiences and lay claim to truth.

But it isn’t only public knowledge that suffers because of American social scientists’ reluctance to study the rest of the world. There are consequences for the academy, too. When social science models and theories are built nearly exclusively with US and European evidence, knowledge itself is weakened because the very lenses through which questions are asked and answers are sought are biased towards these kinds of places. This is precisely the dilemma that led the Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell to propose that social scientists put what she calls “southern theory” – scholarship produced outside the global north – front and centre in their enquiries. But only a fringe-few American social scientists have seriously engaged with such ideas.

Social science need not be myopic, however. University leaders could incentivise more cosmopolitan and, frankly, more relevant scholarship by explicitly celebrating and recruiting scholars who do applied work in regions beyond the US and Europe. Other tools ready to hand include seed funds for promising nascent projects, endowed chairs for regional specialists and leave time to enable transnational collaborations.

But getting at the core mechanisms of social scientists’ parochialism will require action beyond the academy to incubate broader cultural changes in how the global is valued. Parties controlling international rankings and rating schemes, including Times Higher Education, could substantially influence the academic prestige system by producing competitive measures of programmes devoted to regional study. University planners would have fresh incentives to build up regional programmes if their relative status became explicit and metrical.

In the end, though, the strongest incentive to change will be the economic realities of US academia. With fewer tenure-track jobs becoming available for their students in US research universities, senior faculty will inevitably seek overseas appointments for them. But what will these stateside students have to offer their employers: in what languages; on whose topics? Addressing these questions could make for truly cosmopolitan social sciences.

Cynthia Miller-Idriss is associate professor of education and sociology at the American University in Washington DC and Mitchell L. Stevens is associate professor of education at Stanford University. They are co-authors, with Seteney Shami, of Seeing the World: How US Universities Make Knowledge in a Global Era (Princeton University Press, 2018).

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Beyond the backyard

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?