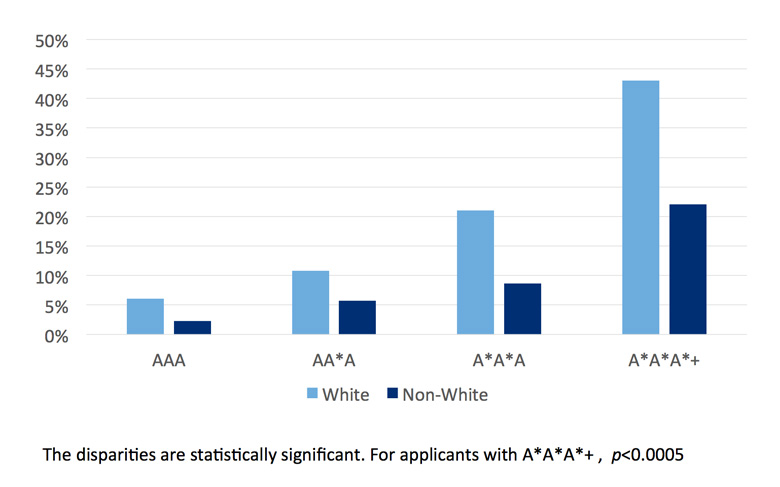

In 2013, I obtained admissions data, reported in The Guardian, that showed that white applicants to the University of Oxford with the same A-level grades were up to two times more likely to be admitted than their black and minority ethnic counterparts to two of Oxford’s most competitive courses – medicine, and economics and management – during the admissions cycles for entry in 2010-11. The disparities persisted even for students who scored three A* grades or higher at A level – grades that were achieved by less than 20 per cent of Oxford applicants.

My aim was to rebut two stock arguments used by Oxford to explain away the published ethnic disparities in its admissions statistics. One is that they are the result of BME applicants applying disproportionately to the more competitive courses. The other is that some ethnic minority groups have lower average A-level grades than white applicants. These are arguments that various media outlets still repeat ad nauseam.

Recently, David Cameron announced a new government policy proposal to require universities – particularly Oxford and Cambridge – to publish their admissions data regarding ethnic minorities. As the universities were keen to point out, they already publish annually their headline figures, usually the overall success rates for BME applicants.

The figures are consistently lower than the success rates for white applicants, but the universities find it easy to deflect accusations of bias by insinuating that the disparities are a result of the issues mentioned above, course choice and A-level grade – which, conveniently, the data they publish do not take into account. By providing a plausible sounding explanation, supported with little or no evidence, the universities, it seems, are almost effortlessly off the hook. For proper transparency, more detailed admissions statistics that control for at least the most relevant variables are needed.

After much difficulty and a few appeals under the Freedom of Information Act, I obtained detailed statistics regarding admissions to one Cambridge course, medicine, for the years 2010-12. These too were published in The Guardian.

Offer rates by ethnicity and A-Level grades for UK applicants to medicine at Oxford University for entry in 2010-2011

They revealed a statistically significant disparity in the admission of BME applicants with the highest possible A-level grades, which suggests that bias during interviews is a likely factor. As a Cambridge spokesperson was quick to point out, even this more detailed analysis did not take into account other variables, such as admission test scores or interview performance. This only shows that there is a need for the publication of more statistics that take into account these other variables, too – if only Cambridge would release them.

A further analysis of Oxford admissions data that we carried out showed that school background did not explain the ethnic disparities. Indeed, using data from admission cycles for 2010-12 intake, we showed that white applicants from state schools with the same grades were more likely to have been admitted than BME applicants from any type of school, including private ones. One telling statistic is that while 23 per cent of British Chinese applicants who sat A levels scored three or more A* grades, only 15 per cent of applicants from this group were offered places. By contrast, only 17 per cent of white applicants who sat A levels achieved the same level of success, but 26 per cent received offers.

Whether Cameron’s new proposal will be effective in ensuring proper accountability depends on how it will be enforced. Rather than requiring the two universities to selectively self-report, it may be more effective to compel them to provide a more detailed breakdown along the lines I have suggested. Once data are available from several admission cycles, a thorough, detailed analysis will be possible without running into concerns about data protection and statistical significance.

Such a requirement would be particularly significant given the recent attempts to exempt universities from the Freedom of Information Act, which is the only existing means to access detailed admissions data that universities do not publish.

Kurien Parel is a DPhil student in engineering science at Christ Church, Oxford.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?