The soaring cost of student living

The cost of living away from home in a big city to attend university is getting out of hand. Students from around the world share their stories.

Share

In April 2013, Ellie Wood dropped out of her undergraduate degree at the University of Liverpool, just seven months after starting.

In this time, she’d been forced to take on crippling debt just to afford university housing and the other expenses that come with living in a big city. Ultimately, the cost was too much to bear.

Ellie admits that she got swept up in the excitement of going to university and living away from home for the first time. Without any plan as to how to make her money last, she accepted a room in new student halls, even though it was the most expensive option, at £130 a week.

“It was fabulous, but I found myself surrounded by people who didn’t have money worries like I did, making it very easy to forget my own problems,” she explains.

Now she lives at home with her parents, studies at the University of Coventry and has worked in retail jobs and undertaken internships to support herself.

About her life in Liverpool, she says: “It was crazy expensive. The nearest supermarket was a £10 taxi ride away from my flat despite living quite close to the centre; buying food wasn’t expensive, but going-out costs and the cost of things to do was really high.

“It meant I spent a lot of time in the flat, with or without other flatmates. My student loan covered around 80 per cent of my accommodation, so my savings I had when I went to university covered the other 20 per cent.

“I then had to survive on a credit card and my overdraft, both of which I am still paying off now.”

The rising price of property is an endemic problem in academia, where universities are often clustered in big, expensive cities.

But unlike professional staff and academics, students face the additional burden of trying to manage their finances for the first time while also feeling the social pressure to keep up with their peers.

In many cases, renting accommodation either from the university or the private sector is simply not an option. Students around the world are choosing to live at home, and so focusing their university applications only on institutions in their hometown.

While living with the family may not provide the coveted “university experience”, it’s the only choice when campus accommodation is no cheaper than private properties, or when demand for subsidised student housing far exceeds availability.

In Frankfurt, even suburban areas are too costly for students, as prices are driven up by city professionals settling in the countryside.

Felix Simon lives with his parents in a small town to the south of Frankfurt and commutes to university. Student-quality private accommodation would have set him back at least €350 a month in the city, and the competition for student housing is high.

He says: “If one likens the situation to London, Paris or New York, Frankfurt is still laughably cheap – but for many students the high cost of living is a reason to opt for ‘cheaper’ cities such as Berlin or Leipzig when faced with the choice of where to study.

“I have many friends at different German universities who shake their heads in disbelief when I tell them what is considered a ‘normal’ rent in Frankfurt.”

In Frankfurt, as in other major cities around the world, rent is not the only drain on student bank accounts that directly results from inflated costs in urban areas.

Felix reports other steep living expenses such as food, travel and leisure activities, echoing the experience of Ellie and that of many others who find themselves unable to stretch their meagre resources enough to make rent, without even considering other essentials.

The contrast between living expenses at home and at university can be particularly stark for international students.

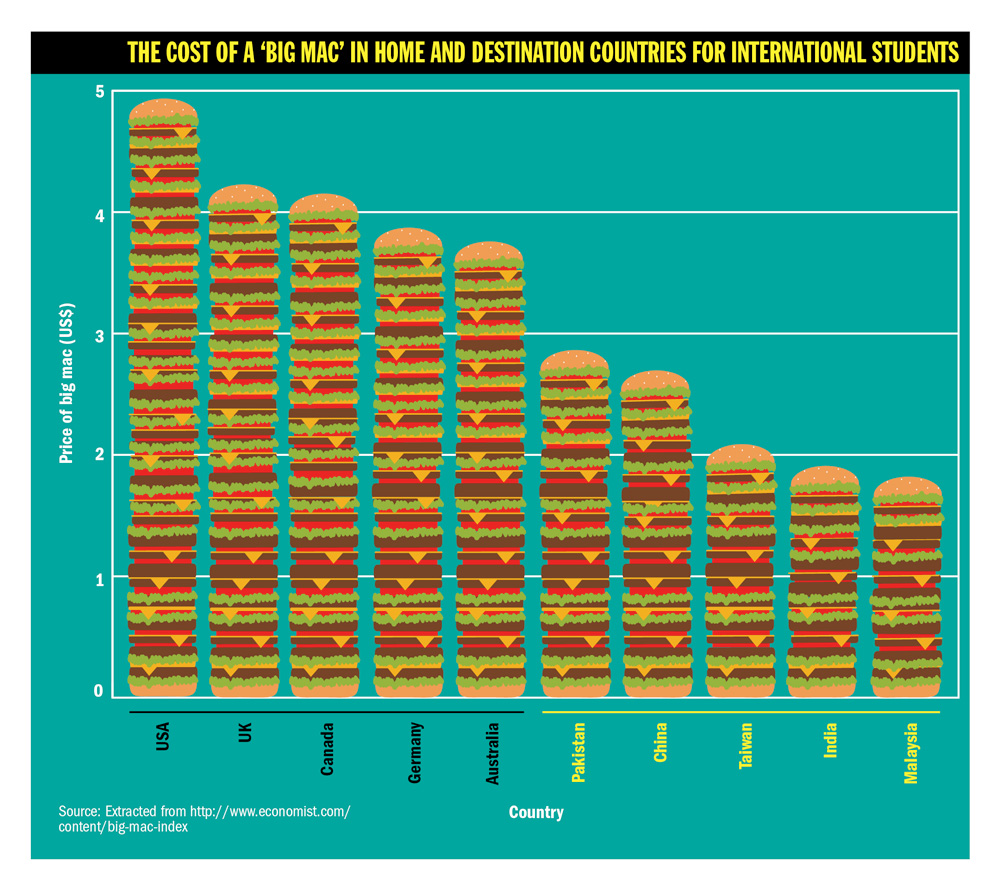

According to the 2016 “Big Mac Index” by The Economist, the price of a Big Mac burger from McDonald’s is 63 per cent cheaper in Malaysia than the same burger in the US. In Pakistan, the price is 32 per cent cheaper than in the UK.

Used as a guideline to the value of different currencies, the index also reflects the varying living expenses around the world because the very same product will set students back widely different sums of money in destination countries such as the US, Australia, Canada and the UK, compared with home countries such as India, Pakistan, Taiwan and Malaysia.

This is not to say that the situation is necessarily easier for those who remain in their home countries because much depends on the situation with national financing for students.

According to recent research reported by the Malaysian Insider, a national crisis in the cost of living is having disastrous effects on students, some of whom feel obliged to send part of their stipend home to support their families.

Out of 25,632 students surveyed at six public universities, 74 per cent admitted to not having enough money to eat.

A poll of European students by Uniplaces revealed this week that 55 per cent of students found that their desired property was out of their budget, and more than a third said that they had struggled to find accommodation because of a lack of availability.

In London, deep unhappiness with both the cost and the quality of student housing provoked students at University College London to “strike” by refusing to pay their rent.

One of those involved, Liam Nagle-Cocco, pays £135 a week for a small room in the cheapest price band. He shares the bathroom and kitchen with nine other people, and is dealing with a persistent cockroach infestation.

Liam can’t help but compare his situation to a friend’s in Cardiff, where a room with an en suite bathroom costs less than £100 week, and the facilities are shared with only four others.

In a statement, a UCL spokesperson said: “We make every effort at UCL to keep rents as low as possible, which is a difficult challenge considering our central London location. Our rents are competitive in comparison with equivalent London institutions, and far less than rates for comparable accommodation in the private sector.”

As explained by Dominique Fourniol, UCL’s head of media relations, the problem results directly from a soaring private property market in London.

He said: “We are absolutely not making any profit on our accommodation. All surpluses are put back into accommodation, improving the estate, acquiring new buildings and so on. We do what we can to acquire these on what is obviously a very competitive market – and our rents are markedly lower on average than the private sector’s.”

However, Liam is withholding his rent payments because he feels that the university should take more responsibility in helping to find a solution to the student rent crisis in London.

He says: “In London, students receive higher student loans, so I think universities know they can charge students more without causing too much trouble. This is fair enough to an extent.

“However, accommodation takes up a much higher proportion of my student loans than most of my other friends.

“Because of high rents and property prices in London, I think universities know that students have no alternative; there’s nothing cheaper. But as a university, they should be seeking to help students in this difficult situation, not take advantage of it.”

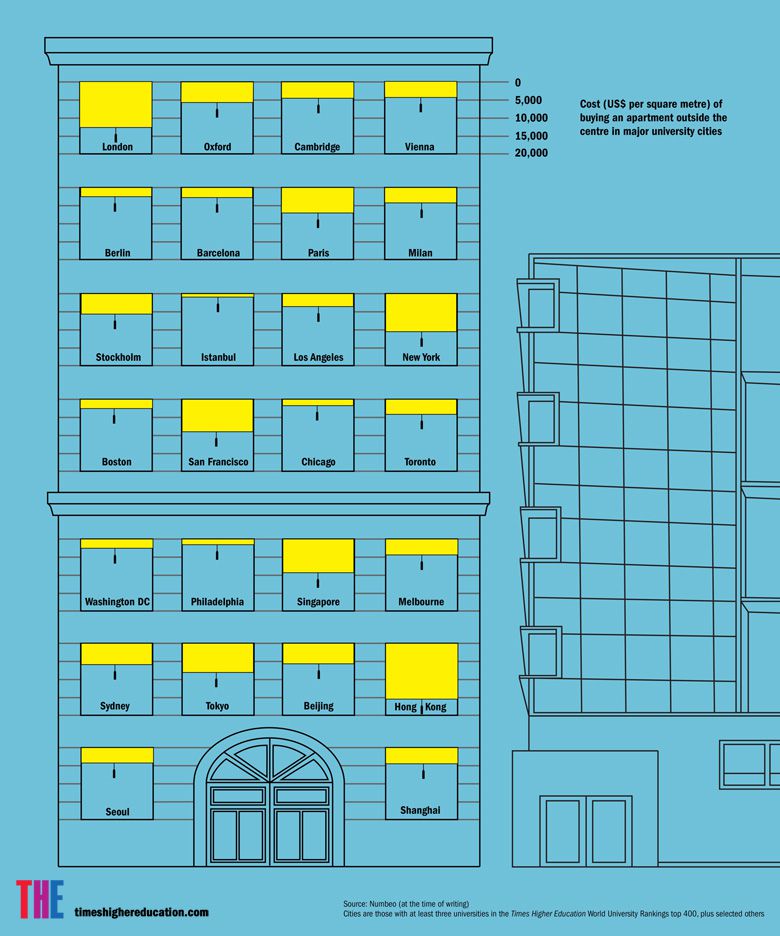

Property markets in major university cities

While Liam saves money by making packed lunches, forgoing student club nights and travelling by bike, other students faced with the prospect of extortionate costs are simply turning down opportunities to pursue higher education at all, or travelling unreasonably long journeys every day to get to university.

Olivia Firth feels that she didn’t have any options when she was deciding to go to university. Even after restricting her study choices to the North of England, where the cost of living is cheaper, she couldn’t afford to rent privately or take a tiny room on campus in the range of £106 to £150 per week.

She lives at home outside York with her parents. To fund her commute to the University of York, as well as other student expenses, she has to work full-time in her summer break and part-time the rest of the year to supplement the student loan she receives.

She says: “There are a few students who I know that are in the same situation as me; many of us stay at home and commute into university together, and those who live at university have had to get part-time jobs to fund their lifestyle and education.

“It might be a four-hour round trip daily due to bad transport links, but it’s still much cheaper than living in the city.

“Accommodation prices are deterring young people from furthering their education, and rising prices are yet another blow to cash-strapped students who are already facing at least £50,000 debt.”

The situation in the North of England may not, in fact, be much better for students than in London, but in Singapore at least, it is not quite so dire.

Sharad Kumar Pandian, from India, studied at Nanyang Technological University on the outskirts of the city.

As an international student, he was eligible for the cheap campus accommodation, which costs at most only half of the rental prices for private properties.

He says: “NTU has pretty good on-campus housing; there are 18 halls of residence where students can stay.”

Even though most local students stay at home, for cultural and financial reasons both, there is simply not enough low-cost university accommodation to go around.

Sharad explains: “One major problem is that NTU doesn’t have enough space. Although they do build new halls of residence – two were opened only two years ago – there’s still a lot more demand than actual space.”

Nonetheless, Sharad, and Liam on the other side of the world, agree that the only obvious solution to the exorbitant private property markets in university cities is for universities themselves to subsidise housing.

For Ellie, the cost of living crisis runs deeper than this. “The pressure to live a lifestyle you cannot afford as a student will still, more often than not, win,” she says.

In the absence of an adequate student loan or grant system that can cover soaring rent costs, Ellie feels that the responsibility is on students to manage their finances or find a way to make a tight budget work.

“A key factor in changing student spending behaviour would be to make sure students are all more educated before they start university. I’ve heard of people who have spent their whole student loan and overdraft in freshers’ week, thinking it would be replenished the next month – which, of course, it wasn’t.

“I think that asking students without this knowledge to budget for three months is a big ask, especially those who haven’t lived away from home before.”