Are you a jack of all GenAI?

You might think that a few well-directed prompts can produce a PhD-worthy thesis or a new app. Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) and its latest achievements are hard to avoid, after all, feted in blog posts and news articles. But can it (and a short course in prompt engineering) replace the deep expertise that comes from years of study and experience? Where does human intelligence meet artificial intelligence and how can we better support humans in this interaction? In short, what is GenAI proficiency, and how do we acquire it?

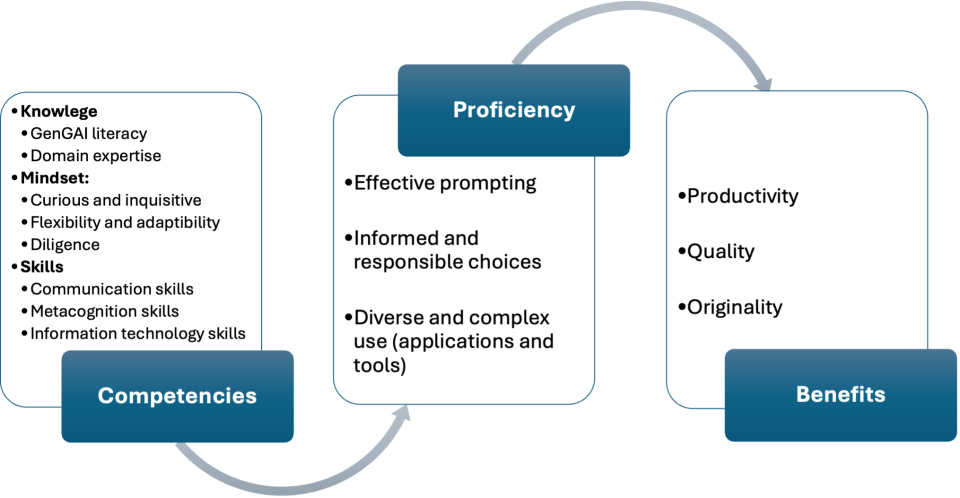

Beyond prompt engineering, effective use, our research has found, maximises benefits such as quality outputs, innovation and productivity, while avoiding risks. Ineffective use, on the other hand, includes failure to realise productivity benefits, adopting incomplete or inaccurate output or uploading sensitive data.

The role of human skills and knowledge as use of AI (and GenAI, in particular) has proliferated has been a focus of our work in the Collaborative Intelligence Future Science Platform (CINTEL FSP), a strategic research initiative of Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO. Over the past year, we have interviewed expert users of GenAI tools to explore what proficient use looks like and what competencies support it. Proficiency was inferred from examples of effective and ineffective use provided by knowledge workers across roles and industry sectors (such as scientists, designers, teachers, legal practitioners and organisational development advisers) who are recognised as expert GenAI users in their respective fields.

GenAI proficiency boiled down to three aspects:

- effective prompting

- informed and responsible choices

- diversity and complexity of use and tasks.

Prompting is how a user asks the GenAI tool to perform a task. Our research revealed that effective prompting requires more than basic knowledge and practice. Rather, it necessitates an array of competencies (and, yes, practice as well).

- AI transformers like ChatGPT are here, so what next?

- DeepSeek and shallow moats: what does it mean for higher education?

- Here are seven AI tools you should be using for your teaching and research

Informed and responsible choices mean using the right model for each task, taking privacy into account and making ethical decisions when delegating tasks to the technology (such as planning workflow) or while prompting. It also involves calibrating trust and staying engaged with the output to make educated decisions on how to use it.

Diversity and complexity of use and tasks involve working with a variety of tools for a range of tasks, with varying complexity (for example, using it to polish one’s writing versus to build a multi-agent GenAI system).

Essential competencies that underpin GenAI proficiency

So, what are the skills, knowledge and mindsets that support proficient use of GenAI tools?

Domain expertise

Nearly all interviews identified knowledge relevant to the task being performed as a requirement for proficient use of GenAI tools. Even though GenAI can reproduce a vast amount of information and knowledge, it is only when a human employs their domain expertise to prompt the GenAI that it will produce relevant, appropriate output. This expertise includes understanding terminology and contextual information. Human expertise is also required to verify and potentially augment the outputs and weed out hallucinations.

GenAI literacy

Another key form of knowledge is GenAI literacy. Understanding the relative strengths and weaknesses of these tools, specifically knowing which tools are available, how to interact with them and their risks, will enhance prompting. The frequent arrival of new models has made GenAI literacy particularly challenging.

Thinking and communication skills

Traditional academic skills – including communication skills, critical thinking and metacognitive skills – balance the temptation to naively or absent-mindedly outsource tasks to AI. Verbal communication, including perspective-taking, was mentioned as important for crafting good prompts and providing feedback that elicits the best response from the GenAI tool with fewest iterations.

Critical thinking is the ability of users to apply their own judgement about the GenAI’s outputs rather than simply accepting what is produced. Metacognitive skills involve self-reflection, planning the work, monitoring progress and reflecting on performance. This helps users identify how GenAI can be applied, how to create appropriate prompts and the ways in which GenAI output could be improved.

Prior programming knowledge

Experts who use GenAI in more complex or novel ways often have a programming background, our interviews found. GenAI tools can be used via simple text- or voice-based interactions, but programmers who could access the models through coding languages and bypass the interface limitations (for example, the number of tokens – typically, a token is a word, character or subword allowed in input or output) achieve more innovative and novel outcomes.

Play, curiosity and an inquisitive mindset

As this technology does not yet come with an instruction manual, curiosity and inquisitiveness, plus persistent play and experimentation, help users to gain proficiency. The mindset is to be continually learning and sharing information to keep up with evolving GenAI tools. This approach is likely to remain necessary.

Proficient users are also flexible, adaptable and diligent. Flexibility is useful not only in refining prompts to improve results but also in thinking about the work in general and aligning tasks with what GenAI can do. Expert users are diligent, aware of the potential for errors, and carefully inspecting the GenAI’s responses rather than blindly trusting them.

How AI leads to a revaluing of human intelligence

Earlier versions of AI could only perform well-defined tasks. Today, GenAI tools can be used for a wide variety of tasks, offering a path to enhancing knowledge workers’ performance. While mastering GenAI requires good prompting skills, it is merely the beginning. To harness its full power, users must be strategic, informed and adaptable. Embracing an active approach, continuously learning and staying updated with the developments in this rapidly changing area, experimenting with different tools, expanding the range of tasks the tools are used for, investing time and not being discouraged if desired results are not immediate are the building blocks of proficiency.

Although some technologists claim that super-intelligent AI is imminent, the GenAI competency framework we present suggests that current tools still lean on human intelligence as a complement. By recognising this and using them in tandem, one can unlock the potential of GenAI.

Einat Grimberg is a postdoc in the skills project within the Collaborative Intelligence Future Science Platform (CINTEL FSP); Claire M. Mason is a principal research scientist who leads the technology and work team in Data61 and the CINTEL FSP’s Skills project; Andrew Reeson is the research leader of Humans & Machines group in DATA61 and assistant director of CINTEL FSP; and Cécile Paris is the chief research scientist and director of the CINTEL FSP; all are at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

Additional Links

The full preprint “Building proficiency in generative AI: key competencies for success” is available here.