On climate change, are universities part of the problem or part of the solution?

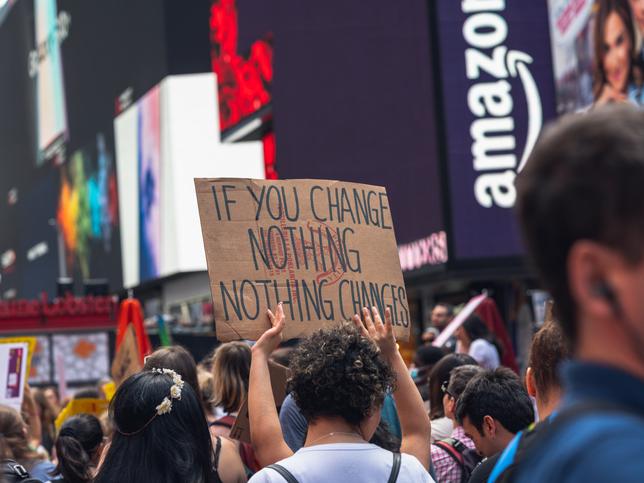

Despite 30 years of international climate negotiations, climate destabilisation is threatening the livelihoods of billions of people, and dangerous climate disruptions are becoming more frequent and extreme all around the world. The COP-29 meeting in Azerbaijan demonstrates yet again the ineffectiveness of our collective efforts to respond to the devastating injustices of the climate crisis. Another year, another COP where those profiting from fossil fuels continue to prevent transformative change.

Although the science is clear that fossil fuel phaseout is the number one thing that is urgently needed, powerful fossil fuel interests have successfully captured the policy agenda. The fossil fuel industry is making higher profits than ever before and, rather than being phased out, global fossil fuel extraction is expanding.

- Greening your university is not optional; it’s urgent

- Bridging the SDG awareness gap

- Engaging staff to drive sustainable change

Within higher education, many of us are asking ourselves what is our role in and responsibility for the ineffectiveness of society’s attempts to confront the climate crisis? Have our universities’ efforts on climate and energy been sufficient? Given how fossil fuel interests have been strategically investing in higher education for decades, has academic research and teaching been reinforcing and strengthening the climate obstruction agenda of fossil fuel interests, rather than resisting or weakening it? Many are also asking whether higher education institutions are effectively creating and disseminating knowledge on alternative regenerative economic and social systems, available to replace the extractive and exploitative systems that are causing so much devastating ecological harm, human suffering and climate injustice?

In considering these questions, some may say that universities are part of the problem. Most universities are failing to prepare students for the disruptive future ahead, and many students complete their degrees without learning anything about the incompatibility between basic assumptions of economic growth and the Earth’s planetary boundaries. By continuing with business as usual, higher education institutions could be accused of normalising complacency about the rapidly deteriorating health of the Earth’s system, on which all of humanity depends. While many universities provide courses and institutional initiatives related to climate and sustainability, they’re increasingly being accused of greenwashing, as their efforts are rarely transformative. University research on climate and energy suffers from “academic capture” by industry interests, which partner and fund universities to legitimise and advance their profit-seeking agenda.

But others are increasingly viewing universities as powerful institutions to be leveraged for the transformative shift toward a more stable and healthy climate-just future. New global networks of academics, dedicated to knowledge dissemination and co-creation for the public good, are resisting academic capture by industry and reclaiming their universities’ impact agenda for the public good. Expanded interest in a diversity of economic frameworks, including ecological economics, feminist economics, doughnut economics and post-growth economics, are broadening policy discourse beyond the narrow neoliberal market fundamentalism that has dominated and constrained academic analysis to inform pathways toward more just and stable futures. Recognising higher education as critical social infrastructure, university professors, administrators and staff are increasingly leveraging their collective power to encourage and support transformative thinking, research and learning toward climate justice.

As a transdisciplinary academic working on climate, energy and environmental justice, I have been engaging with the potential of higher education to advance a more healthy, equitable, climate-stable future for over three decades. In my 2024 book, Climate Justice and the University: Shaping a Hopeful Future for All, I explore an alternative reimagined vision of higher education as a societal resource for the transformative changes that are urgently needed to reduce human suffering and restore ecological health.

In the book, I propose climate justice as a paradigm shift, one that sees the climate crisis not as an isolated problem that needs to be “solved”, but as a worsening symptom of a deeper systemic issue of the extractive and exploitative structures currently dominating human societies. Imagining a new model of “climate justice universities” encourages us to open up our collective thinking to reconceptualise how higher education could be restructured to advance the public good and a better future for all.

To allow higher education to reclaim its public-good mission and more effectively address the rapidly changing needs of vulnerable communities, climate justice universities would be publicly funded and geographically distributed. Instead of universities functioning as financial enterprises reinforcing individualism, commercialisation and the corporatisation of higher education, climate justice universities would prioritise access for all, collective action, civic engagement and ecological health. They would encourage local action and global solidarity.

During this disruptive and destabilising time, efforts to reclaim and restructure higher education are gaining traction. As academic freedom is being increasingly threatened by the power and influence of wealthy donors, influential politicians and corporate interests in higher education institutions around the world, those of us working within universities need to become more actively involved in protecting the public-good mission of higher education; by, for example, joining the Climate Justice Universities Union – a new international collective advancing transformative change in higher education.

It is increasingly clear that universities are an underleveraged resource with untapped potential to contribute to a more just, healthy and climate-stable future. Expanding our collective thinking about a shift toward climate justice universities is one way to stimulate new ideas and catalyse different conversations about the powerful ways that higher education can shape a hopeful future for all.

Jennie C. Stephens is professor of climate justice at Maynooth University in Ireland and professor of sustainability science and policy at Northeastern University in the US, and author of Climate Justice and the University: Shaping a Hopeful Future for All (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024).