Cut down your marking time by using whole-class feedback

You may also like

Providing quality feedback is a key part of assessment. But it also takes time that many educators don’t have.

What is whole-class feedback?

Whole class feedback is a method a marker can use to increase the efficiency of marking a large number of assessments. The marker uses a rubric as per normal to address criteria, but instead of adding detailed and often repeated comments where they see gaps or strengths in students’ work, they undertake mini qualitative data analysis and look for patterns or themes in the responses. These findings are then presented to all students as an attachment to their assessment, and students are encouraged to use both these and the rubric indications to evaluate their own performance against the assessment’s intentions.

How to do whole-class feedback

- Prime students with clear explanations and examples of how you will use whole-class feedback when marking their assignments well before marking begins.

- Model for them how they should use the whole-class feedback to self-evaluate their grades.

- If you have multiple markers who mark for their own tutor group, provide them with instructions on how they should use whole-class marking.

- During marking, write down observations of responses to criteria and categorise them so they align with the rubric criteria.

- Assign grades in the rubric as you would, but instead of commenting on each criterion or at the end, add a link to the whole-class feedback document, or as an announcement when releasing the grades.

- If you are a casual marker, provide your feedback to the course coordinator.

Saving time

Saving time in the writing of comments by using a predefined bank of comments is not a new method, but its downside is that the comments can seem disconnected from the work and not contextually relevant or useful in helping students understand how their assessment has been graded. More importantly, students are left unclear about how this feedback will help them in their next assessment.

- Four directions for assessment redesign in the age of generative AI

- Written feedback for students – keep it clear, constructive and to the point

- How consensus grading can help build a generation of critical thinkers

Whole-class feedback is more precise. The comments emerge through the marking process as the marker observes patterns of responses. If the rubric is written well enough, then at the individual level it does most of the talking through the criteria. If you have made your students aware of the whole-class feedback approach, they can use the rubric indications and cross-check them against the whole-class feedback document to evaluate their performance and understand the grade they received.

Encouraging self-regulatory learning

There will still be some occasions where an individual comment will be necessary, usually when a student has seriously misunderstood a criterion. But these occurrences will be in the minority and not cut into the overall saving in marking time. By providing the opportunity for students to be active in understanding their feedback by cross-referencing the rubric grade against the whole-class feedback, you will encourage greater self-regulatory behaviour. Instead of just seeing the grade and moving on, having to work at understanding why a grade was received places the student in a stronger position to be able to act on their findings in future assessments. Of course, some will not go to these lengths and only view their grades, but this is what such a student would do anyway, regardless of how much time and energy you spend providing written feedback.

Closing gaps

Another benefit of this approach is that it helps identify if the rubric is fit for purpose. Whole-class feedback may uncover that some or all of the criteria are not providing enough guidance for the students. Some tweaks in the writing of the descriptions or, in fact, the writing of a criterion itself may be needed, as the pattern of student responses highlights that the intention of the criterion is not coming across. If it’s not the criterion that needs to be adjusted, the learning sequence related to the criterion may need to be rethought, or further resources provided to learners.

Perhaps less frequently, it may be that the pattern of responses indicates that the entire assessment is not achieving what you had hoped it would achieve in meeting course learning outcomes. Whole-class feedback provides you with real-time contextualised action research to inform such decisions.

Worked example

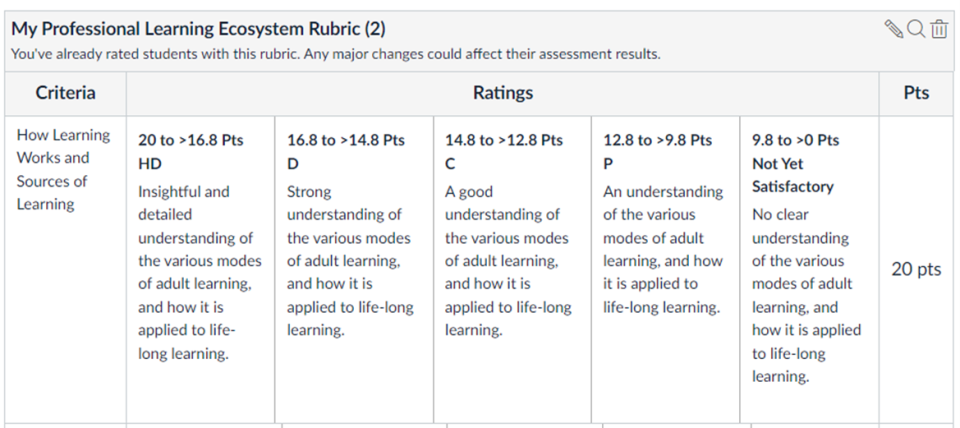

In the example below, taken from a recent assessment, the comments you see are from my observations of how students responded to two of the rubric criteria, the first asking them to discuss and describe their understanding of “How learning works” through the use of a case study, and the second a “writing” criterion.

‘How learning works’ criterion

- Students who didn’t discuss particular aspects of the learning process that were emphasised repeatedly throughout the course did not do as well as those who did in that section.

- Students who explicitly made the connection between how learning works and its implications for future behaviours received a stronger grade. This is because the assignment is about learning, and to put plans into action they needed to consider how learning happens. For example, the learning concept of repetition (interrupting the forgetting curve) would be useful to turn an action into a habit, a necessity when changing behaviour patterns.

- Students who only discussed when learning occurs rather than how it occurs did not receive the strongest grades in that section

- Those who didn’t discuss the case study character in the learning section were not able to receive an high distinction grade in that section.

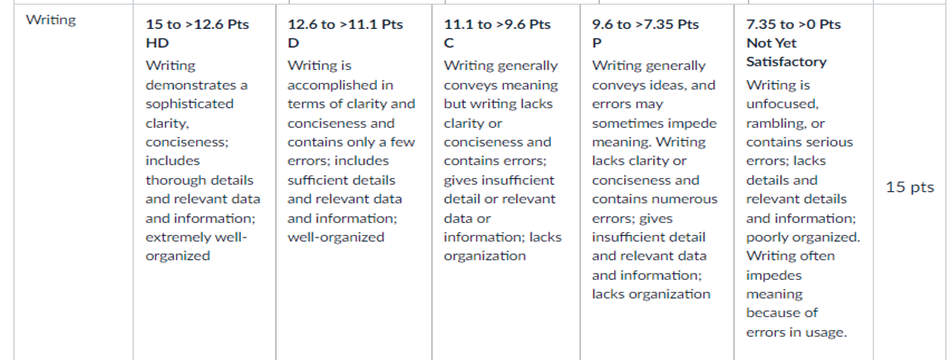

Writing criterion

- Those who constructed a strong opening and introduction and followed through on what they said they would discuss in the report succeeded more than those who didn’t.

- If a section was too short it didn’t get a strong grade.

When referencing, they didn’t get full marks if:

- References weren’t in alphabetical order

- There were five references (or fewer) – not enough evidence to suggest a pattern

- They didn’t follow the Harvard model

- Dates did not follow the model

- In-text citation was incorrect

- Some referencing was correct but not all

- Italics were used inconsistently.

Paul Moss is learning design and capability manager at the University of Adelaide.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.