As a researcher, you need a personal strategy…could business frameworks help?

“What is your strategy?” This question is likely uncomfortable for an academic researcher. In academia, we don’t usually think in terms of personal strategy, since this often depends on the project we are involved in, the stage of our career, or the topic of our research. But the question could be approached using simple business frameworks, treating yourself as a company of one, to address a few key issues. Let’s first paint a broader picture on our way to the personal strategy, which could provide a useful direction.

Your why, who, what and how

These questions do not have simple, unique answers. In fact, you can peel off several layers for each. Taking Toyota as an example, its Toyota Production System (TPS) is the system implemented by the company to specifically reveal the root causes of any problems in the production by asking “why?” five times.

Let’s try this approach ourselves. So, ask yourself the following:

Why are you doing your current activity? Why is that important to you? Why do you give priority to that issue? Why did you reach this decision? Why do those factors matter?

Who is your intended audience, broadly speaking? Who in this broad audience can most likely constitute your target segment? Who in this segment may be most affected by your value proposition? Who can you picture as the audience directly listening to you at an event? Who, after all, do you have in mind when you design your research activity?

What are you really doing, as an individual in your current career position? What is the essence of your activity? What is the dominant component that gives the flavour of this essence? What do you see if you further break it down? What do you control and what is controlled by your environment in this picture?

After clarifying your motivation, your audience and your value proposition, it’s time for the simplest part: How do you plan to create or enhance the value proposition intended for your audience? How do you organise it for presentation? How do you deliver it? How do you fund the efforts for this delivery? How do you support these activities by your capabilities and your continuous learning?

Work on making the gap between your present Why-Who-What-How and your ideal Why-Who-What-How ever narrower.

- Resource collection: What I wish I’d known about academia

- Academic CV writing dos and don’ts

- You can have it all, just not all at once

How to find the key success factors?

Japanese organisational theorist Kenichi Ohmae’s famous 3C framework encourages businesses to focus on customers, competition and corporation. Let’s apply it to personal capabilities.

As a researcher, precisely defining the consumer of your activities (“customer”) and the competing actors (“competition”) is essential, but can be difficult. The “customer” depends on your career stage as a researcher and your specific situation, ranging from your peers to funding providers, but also to the policymakers or society as a whole. On the other hand, the “competition” can be more precisely defined, as the peers (or other research groups) that address the same scientific questions or are active in the same research field. Your key success factors (KSFs) lie at the intersection of your customers’ key buying factors (what drives your perceived customers’ demand for your research) and the capabilities or limitations of your competition, which may define where your capabilities could be most valuable. By asking “How can I meet the key success factors?”, you can discover characteristics of yourself and your work that are unique and give you greater originality.

How to find the pressure points in your specialism?

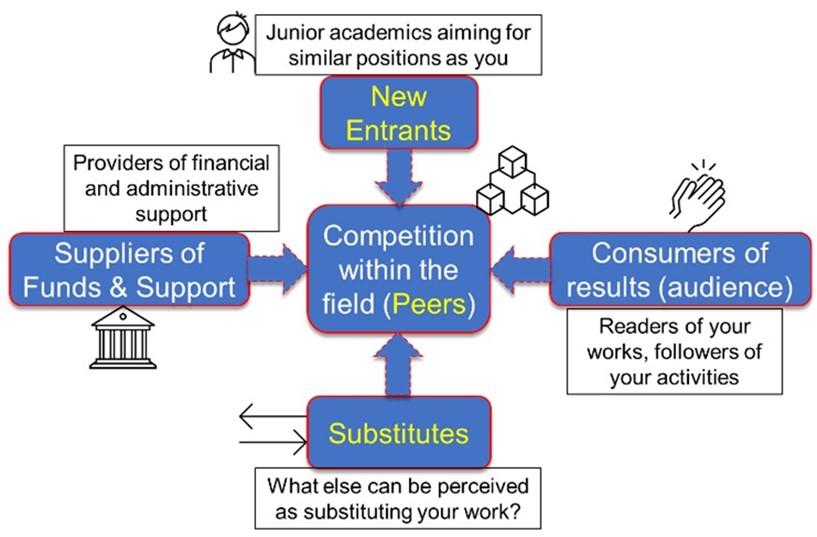

Porter’s Five Forces indicate the competitive forces at work in your sector that may influence your ability to be successful in your field. For an academic environment, the illustration here can capture a few aspects of the five forces framework looking at: competition, new entrants, substitutes, suppliers and – most importantly – customers, all “translated” into the terminology of an academic environment.

For most academic researchers, the strongest pressure comes from the competition within the field, from your peers. It is, therefore, reasonable to start your analysis of the five forces from your “competition”. This way, you could identify things you can do or change to raise your standards or differentiate yourself.

“Competition” is not static in an academic environment, but always changing. Consider new entrants – that is, peers who were not “competitors” until recently but who have become significant players. If you are at an early career stage, they may be graduating PhD students, postdoctoral researchers, or experts from industry who decided to take on the challenge of an academic career. They may not directly be competing with you in the short term, but they may bring disruption to your area of work in ways that favour their capabilities. You must, therefore, be aware of the existence of new entrants and the skill set and mindset they bring.

Look at “substitutes” that can replace your value proposition with an upgraded one. If considering lectures, a substitute could be any equivalent lecture offered on an e-learning platform or offered for free by another institution or education provider. If you are considering research output, a substitute could be a material, method, phenomenon that can bring the research field to the same result you aim for, in a more efficient, elucidating or elegant way.

There is often pressure from suppliers, which may provide the materials, equipment and software necessary for research. This pressure increases when dealing with advanced research that requires sophisticated customised equipment. It is rare to find empathetic suppliers that seek a truly win-win partnership. However, you should still contribute to the development of a mutually beneficial relationship. This means understanding the suppliers’ immediate targets but also that the success of your research can be a source of promotion for their business.

Finally, the consumers of your work, such as other researchers, funding agencies or society, more broadly, may put pressure on your work. The rapid pace of societal, cultural, economic and technological change may result in changes to the needs of your research audience. Meeting such needs is fundamental to research success, so stay mindful of what the consumers of your research truly want in order to remain successful. One example is funding agency requirements, since these are often seeded in the needs of the society that is the source of those funds.

We all have a desire to be the best version of ourselves and this requires a strong drive which a personal strategy can provide. Let’s enjoy searching for it, with the help of these frameworks.

Daniel Moraru is principal investigator and associate professor at the Research Institute of Electronics, Shizuoka University.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.